Here at WDJ, we’re always on the lookout for products that improve life with our dogs in any way. Every year, we talk with our experts and determine the toys, training and care tools, and treats that provide the biggest lift to them and their canine companions. These are their top picks for 2025!

Whole Dog Journal Contributors Choice

Saint Rocco’s Dog Treats

Price: $24 for 16 ounces

High-value training treats are the ones you use when you’re teaching your dog something that requires a bit more effort or that you want to stand out as something special, like a jackpot after a tremendous agility run. Saint Rocco’s Dog Treats—especially the salmon variety—are just that. These treats look and smell like real food. My dogs notice as soon as I open a bag. Even the cats come snooping around!

St. Rocco’s was founded by two brothers who had their college careers interrupted by COVID-19 in 2020 and turned the experience into opportunity with just a clean kitchen, small investment, and advice from their dad and granddad, both with pet-food industry experience. And, of course, their dog Cooper, who served as taste tester.

The treats are hand-made, limited-ingredient, contain only human-grade ingredients and no preservatives, and are fresh-baked daily in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. A sample ingredients list? Here is the chicken variety: Chicken breast, sweet potato, vegetable oil, potato flour, paprika, turmeric, and salt. That’s it.

My dogs love the chicken flavor. My sister’s young dog went crazy for the meat-lover flavor. And we had the attention of every dog in the immediate area when the salmon package was opened.

The treats resemble wide strips of jerky, about five inches long, and have a chewy, crumb-free texture (they range from 21% to 25% moisture). While most types can be torn with your fingers into pieces that are whatever size you want to feed to your dog, we did find the cod flavor a bit difficult to tear. It’s probably more efficient to pre-cut them into smaller bites instead of tearing.

By the way, St. Rocco is the patron saint of dogs. I suspect he would be proud. – Cindy Foley

Yomp FunFeeder

Price: $25

As the owner of two high-speed eaters, I have a large collection of bowls that are built with a wide variety of baffles, balusters, and barricades meant to force dogs to eat more slowly. Despite the size of my hoard, though, I have remained unsatisfied with some aspect of each product’s materials or performance: I have several problems with feeding out of plastic bowls (health concerns, the risk of “forever” chemicals leaching out of plastics, the inability to freeze them without the danger of cracking, etc.). The stainless steel slow-feeder bowls are either too simplistic (with a single donut-shaped trough) or with pieces that need to be unscrewed from the base for cleaning.

None of those concerns are posed by the 100% food-grade silicone Yomp FunFeeder bowl. Silicone is one of the safest materials to feed from (it’s used in many infant and toddler eating utensils). This bowl can be filled with wet or fresh food and frozen, and immediately served to a dog out of the freezer; it’s also dishwasher-safe. It’s large enough for a meal for even very large dogs (it measures 9.5″ x 9.5″ x 2.5″), but the baffles inside the bowl are flexible enough that even a small dog can push them around with his nose and tongue to (eventually) reach all the kibble inside. However, the depth of the bowl makes it inappropriate for flat-faced dogs. – Nancy Kerns

Front Range Day Pack

Price: $70

I’ve built up quite a collection of dog backpacks over the years searching for something that fits well, holds the right amount of gear, stays balanced, and doesn’t rub or interfere with my dogs’ movement on the trail. Ruffwear’s Front Range Day Pack has been a game changer in those respects.

Unlike many of the backpacks my dogs have been outfitted with, I haven’t had any problems with the Front Range slipping off to one side. It stays balanced and centered even when my energetic young Airedale, Carmen, bounds up a bank or leaps logs on the trail. It also has loops that hook the undersides of the saddlebags to the backpack harness so they don’t bounce when she does!

The fit of the harness is one of my favorite things about it. Carmen is a deep-chested, high-necked dog with a narrow waist—not always the easiest shape to get a good fit with a backpack or harness. However, the Front Range pack fits like it was made for her. It doesn’t get in the way of her neck or legs and is easy to adjust. The padded harness and belly strap have also been great—even when she wears her pack for hours, I haven’t found any rubs or sore spots.

Of the three leash-attachment points the Front Range offers, I typically use the mid-back attachment, but it’s nice to have the option of attaching a leash to either the rear tow loop or chest loop.

While it would be a bit small for overnight trips, the Front Range Day Pack is, as the name implies, great for day hikes. It comes in four (girth) sizes: XSmall (17-21 inches), Small (22-27 inches), Medium (27-32 inches), and Large/XLarge (32-42 inches).

The medium size works well for Carmen, who has a 27-inch girth. Her pack easily fits two water bottles, some food and treats, dog waste bags, and a collapsible bowl. There are also mesh pockets inside to help keep everything organized and secure.

The Front Range Day Pack has stood up well after nearly a year of use and the pack dries quickly when Carmen inevitably goes for dip in whatever creek or stream is at hand. – Kate O’Connor

Price: $299 – $379

Have you ever tried to grab a quick video of a dog learning something great, only to find that using your iPhone ruins everything? You either 1) spend 10 minutes finding a good spot for your phone mount or 2) you resort to holding the phone, utterly throwing off your natural movement—and the dog’s response.

Enter my new best friend: the amazing Ray Ban Meta Smart Glasses, which contain a tiny camera (that takes still photos or videos of up to one minute), microphone, and speakers. Now, in the middle of any training session, I can capture an utterly authentic video, hands-free: “Hey, Meta, take a video.” The camera in the glasses is always at the right spot, recording exactly what I see. “Hey, Meta, stop.” (You don’t have to speak; you can also take photos or start recording video by tapping the arm of the glasses.)

Using the Meta View app and a Wi-Fi connection, that video can be on my phone in less than a minute, and being watched by my client a moment later. Now they know exactly what their dog is capable of, and they have a video to copy at home that’s much more helpful than trying to remember what they saw me do in person.

I opted for the transition lenses, so they work as sunglasses outside. You can also have prescription lenses put into the Ray Ban frames!

There is a tiny speaker in each arm of the glasses that provides high-quality sound into your ears—without earbuds and without blocking out the sound of your environment. The quality is so good, I use the glasses to listen to podcasts when I’m walking my dogs. They’ll also make calls, send messages, and livestream, but I don’t use those. They had me at quality hands-free video!

The glasses get charged by placing them in their case and using a USB-C cable. The charge lasts as long as four hours of use; when the case itself is fully charged, it can charge the battery in the glasses on the go; the case doesn’t have to be plugged in to charge the glasses.

The Ray Ban Meta Smart Glasses have enough storage to hold 500 photos or 100 30-second videos before you need to download them to your phone using the Meta View app.

At $300+, I originally thought these would be a fun indulgence, but I found they’re a game-changing business tool worth every penny. – Kathy Callahan

The Leader and Lead-All Leashes Multiple-Dog Walking System Starting at

Price: $34

Multiple Dog Walking System

Tiny Horse

Toronto, Ontario

“The Leader” is the foundation of the Tiny Horse multiple-dog walking system. It’s essentially an adjustable lead that can be worn around your waist or across your chest, with an integrated adjustable leash for a single dog. From there, you can add any number of Tiny Horse Lead-All Leashes, which can be snapped onto The Leader in a variety of configurations.

I use this system every day when walking my three dogs; I’ve even walked four when I have a canine visitor. When walking only two dogs they never get tangled thanks to the rotating snaps, and even with three it is quick and easy to resolve tangles.

The waist lead option saves my back and rotator cuffs (not that my perfect angels would ever pull). I particularly love that I can have my hands free while still having control of my dogs. For my summer walks along the roadside, I don’t have to worry about dropping a leash and having a dog dart in front of a car—they are always attached to my waist lead. And all year round I have extra freedom to dole out treats and pick up poop without needing to juggle leashes in my hands.

The company is constantly adding upgrades and new options, and the customization can’t be beat. You can choose from multiple materials and a wide range of colors, plus a variety of accessories to fit your needs and preferences. I opted for the BioThane leashes in neon colors for maximum visibility walking on the road.

My dogs start jumping and squealing as soon as I put on the TinyHorse system, because they know it is time for a long walk! – Kate Basedow

The Curli Clasp Air-Mesh Harness

Price: $31 – $35

Our top priority when shopping for a harness for our dog is comfort. It needs to fit, not bind, not restrict, and not weigh the dog down. The Clasp Air-Mesh Harness made by curli (the company spells its name with a small “c”) is all that.

We avoid harnesses that are so wide in front that it affects shoulder movement. We also don’t want them to be so high in the chest area that it restricts the dog’s ability to put his head down and sniff. The curli Clasp Air-Mesh Harness allows full shoulder movement and fits well behind the dog’s elbows, so he can swing his legs freely. The mesh is soft, and the seams have just a tiny bit of give, adding comfort.

Also, we look for harnesses that are simple to put on the dog, not ones that make you ask, “Which way is up?” That means an immediately recognizable top and bottom and a minimum number of snaps and adjustments. With this harness, a Velcro-type fastener at the top of the dog’s shoulders adjusts the fit and the harness is secured by engaging the push-in snap. The leash ring is integrated into both sides of the snap, so clipping on the leash adds extra security.

Putting this harness on your dog couldn’t be easier. It’s step in, pull up, close the top fastener, and snap it shut. This is especially appreciated by dogs like my big-eared Papillon, who hates harnesses that must be pulled over her head.

We love lightweight but cushioned harnesses—safe and secure, of course—but ones that don’t weigh the dog down. Curli says no harness should weigh more than 2% of the dog’s weight. We agree.

The curli harnesses are made in Switzerland and available at large retailers like Chewy and Amazon. This curli Clasp Air-Mesh Harness is particularly designed with small- and medium-sized dogs in mind, but curli offers seven sizes from XXX-S (dogs from about three to six pounds and with a girth of about 10.5 to 12 inches) to XL (about 26 to 40 pounds and with a girth of about 22 to 25 inches).

The Clasp Air-Mesh Harness has reflective strips on it, but I have my eye on a new curli release that is fully reflective. I’m now a curli fan! – Cindy Foley

Thule Allax Crate

Price: $800 – $1,000

I’ve tested nearly every crash-tested dog crate on the market, and the new Thule Allax is a car crate to keep an eye out for. Released in September 2024, the Allax crate is similar in design to Variocage crates, but with some serious design improvements. The comparable Variocage single is not only more expensive (starting at $930), it’s also more difficult to assemble and more difficult to adjust its size.

Thule’s Allax crate has a similar sliding design to the expanding and contracting Variocage single, but instead of fiddling with multiple screws, it just has two side levers that can be opened to allow you to adjust the length of the crate to your car. Its assembly was simple; it took only about 30 minutes for me to put together. Having tested both, I’m of the opinion that the Thule Allax is more durable and well-made than Variocage’s crates.

In terms of safety, the Allax crate has been crash-tested in Thule’s Sweden-based testing center—the same location where all of its roof racks, roof tents, and other car-focused gear undergo their safety assessments. The brand simulated multiple types of impacts, performed “wear and tear” tests to test the durability of the crate for everyday use, and conducted driving tests to ensure the crate remained secure in multiple driving scenarios. Thule’s testing team performed a number of ADAC and VTI crash tests on the crate (international organizations known for testing car seats), and the Allax crate is certified by the internationally recognized TÜV SÜD (a European third-party safety endorsement).

Though the Thule Allax is much newer than the similarly designed Variocage and lacks the history of real-life crash results, given Thule’s existing brand trustworthiness, the extensive crash testing, the durable and stylish design, and the lower price, the Allax may be a better option. – Jae Thomas

Miles Kimball Outdoor Help Step

Price: $40

I came across the Miles Kimball Outdoor Help Step when I was looking for a low, non-slip platform to use for conditioning work with my dogs. Intended for use as a “half-step” to reduce stair height for humans with mobility challenges, it had everything I needed but was having trouble finding in dog-specific gear (at least in my price range).

The platform is a little less than 4 inches high and weighs 3.25 pounds, making it easy to move around or toss in the car. The surface has small nubs that help prevent slipping but also have a bit of give to them so they’re not too hard on paws. It sits solidly on the ground and rarely skids, even when pounced on by an enthusiastic canine trainee. At roughly 19.5 inches by 15.5 inches, it’s big enough that my 50-pound dog can sit easily on it and small enough that she can pivot around it.

My dogs and I have been brutally hard on these nearly indestructible steps. Since I bought them (I currently have two), they’ve seen daily use for conditioning work as well as obedience, agility, and trick training. They have been dug at, carried around (not only by me), left outside rain or shine, jumped on, and just about anything else you can think of.

Along with being a useful training aid, I also used these platforms to help my ancient, mobility-challenged dog get up and down the stairs between the house and the yard. And I keep finding new uses for them! – Kate O’Connor

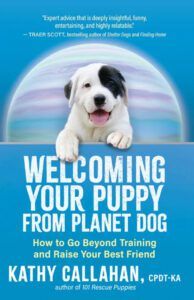

Welcoming Your Puppy from Planet Dog

Price: $19

Welcoming Your Puppy from Planet Dog

Our readers are familiar with Kathy Callahan’s warm, encouraging style of dog training and writing; she’s been a regular contributor to WDJ for nearly five years. Her new book, Welcoming Your Puppy From Planet Dog (New World Library 2024, 219 pages), concentrates a wealth of tips and tactics for smoothly integrating newly adopted puppies (and dogs) into our homes.

Callahan, an experienced foster provider who has raised more than 200 puppies (and trained many more) in the past decade, is aware that many people find raising puppies to be difficult and often aggravating. Many owners struggle with potty training, chewing, puppy biting, whining, and more. Callahan asks adopters to consider their new pups as creatures from another planet—Planet Dog—unfamiliar with our language and customs and in need of patience and empathy as they struggle to adapt to living in our alien world. With great humor and intelligence, she helps new owners consider their aggravations from the puppy’s perspective, in order to find mutually beneficial solutions to every dog/human culture clash.

Best of all, Callahan guides adopters through the process of getting ready for a puppy, setting up the puppy for success from Day 1, and onward through the first weeks and months of a fulfilling life together. – Nancy Kerns

Woof Pupsicle

Price: $20 – $25

We’ve recommended the original Kong toy and West Paw’s Toppl countless times in these pages; they are the archetypal enrichment toys that can be filled with food to occupy dogs. Now we can add a third product to that list, as the Woof Pupsicle adds some improvements to food-filled enrichment toys.

The Pupsicle is a rubber toy that features a treat compartment in the center and openings around the sides that provide tantalizing but limited access to the treat. The toy has two halves that screw together to hold the treat, or unscrew so the halves can be cleaned or a new treat loaded into the center.

Where Toppls and Kongs require you to put in quite a bit of dog food or other treats, the Woof Pupsicle uses less food while keeping dogs busy for roughly the same amount of time. The small amount of food in the Pupsicle is great for managing the amount of treats your dog gets through the day and is especially nice for pups who might not be able to handle an entire Kong full of peanut butter, for example.

The Pupsicle is more convenient to fill than a Kong or Toppl, too. You can either choose to buy Woof’s pre-made Pupsicle refills (which come in five different flavors and are full of healthy ingredients) or make your own using the Pupsicle Treat Tray (sold separately), a four-treat mold that you can fill with ingredients of your choice and freeze to make frozen treat balls for the Pupsicle.

I found that even using the Treat Tray to make four Pupsicle refills at once was far less time-intensive than filling and freezing a Kong every time. I like to mix powdered bone broth and water and freeze the mixture in the Treat Tray. Then, when I want to give my two dogs an activity while I work from home, it’s as easy as popping the frozen balls into their Pupsicles, and my girls will be busy licking away for at least 30 minutes.

The Woof brand refill pops have easily lasted over an hour at a time with my two medium-sized dogs. I also like that the Woof pops don’t make a mess. When making your own and filling the refill tray with liquid, you sometimes get dripping or melting. The Woof brand refill pops, however, are solid even when they’re not frozen so they don’t melt and make a mess.

The Pupsicle is wildly easy to clean; just open it up and wash it in the top rack of your dishwasher. – Jae Thomas