On June 27, 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released an update to two previous advisories regarding dog food and dogs who had developed dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). The release made a splash in the mainstream news – but this is all that most people seemed to get out of the news coverage: “THERE ARE 16 BRANDS OF DOG FOOD THAT ARE KILLING DOGS!”

Unfortunately, this is a wildly oversimplified take-away message. It set off a panic in the countless dog owners who feed their dogs some variety made by one of those companies, and may have inflicted serious financial damage to the companies named (as well as all the retailers who sell them) – this, despite the fact that the FDA stated at the outset of the release that the cause of the DCM cases is still unknown. “Based on the data collected and analyzed thus far, the agency believes that the potential association between diet and DCM in dogs is a complex scientific issue that may involve multiple factors.”

Further, in a “Questions and Answers” addition to the update, the agency says things like, “At this time, we are not advising dietary changes based solely on the information we have gathered so far,” and “It’s important to note that the reports include dogs that have eaten grain-free and grain-containing foods and also include vegetarian or vegan formulations. They also include all forms of diets: kibble, canned, raw and home-cooked. Therefore, we do not think these cases can be explained simply by whether or not they contain grains, or by brand or manufacturer.”

It’s a bit puzzling, then, why the agency named the brands of foods that were reportedly fed to some of the 560 dogs whose DCM cases they are investigating (and even more puzzling: why they didn’t include the varieties of foods that were implicated, just the company names). Naming the companies suggests that those companies were responsible for the dogs’ illnesses, even as the agency denied this as an explicit causation. We’re not usually conspiracy theorists, but this move undoubtedly gave a boost to these companies’ competitors.

We don’t mean to sound protective of the companies. Don’t get us wrong: If it can be proven that a company has knowingly or even inadvertently (through cost-saving measures, say) taken steps that resulted in a previously known or predictable harm to dogs, we’d be happy to help drum them out of business. The point is, the cause of these cases is STILL unknown. So why name the companies, rather than just describe the characteristics of the products that have been implicated so far?

Our guess is that so many people buy and feed products without having a clear reason for doing so, and so many fail to read the ingredients panel and guaranteed analysis – perhaps naming companies was the only way to get owners’ attention, and to alert them to check their foods, and think about their dogs’ condition. If they are feeding a product from one of the named companies, are their dogs displaying any symptoms of compromised cardiac health?

The only explicit advice that the FDA offered to owners wanting to protect their pets came at the end of the update: “If a dog is showing possible signs of DCM or other heart conditions, including decreased energy, cough, difficulty breathing and episodes of collapse, you should contact your veterinarian as soon as possible. If the symptoms are severe and your veterinarian is not available, you may need to seek emergency veterinary care.” This is sound advice – and owners would do well to follow it regardless of what diet their dogs are fed.

Information about the cases

We do believe that the agency is more concerned about protecting our health and that of our pets than protecting industry interests, though, again, naming some (not all!) of the companies was kind of a weird move. However, we very much appreciate the fact that, in an effort to give pet owners and industry insiders more information about the issue, the agency has shared much more information in this update and other linked documents than was previously released.

Between January 1, 2014 and April 30, 2019, the FDA received 524 reports of DCM; this includes some 560 dogs and 14 cats. Some of the reports include cases in which multiple pets in the same household developed DCM – which is why total affected animals (574) add up to more than the number of reports (524). The cat cases are beyond WDJ’s area of expertise and we will not discuss these.

The agency also has received many reports regarding dogs with other cardiac problems, but if a dog was not diagnosed with DCM by a veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist, his or her case was not counted in the totals above. The FDA says it will continue to collect information about these cases, as dogs may exhibit cardiac changes before they develop symptomatic DCM. For more about these changes, see “Non-DCM Cardiac Cases” in this linked addendum to the June 27 update.

Some of the detail included in the update dramatically helps illustrate the immediacy of the issue. Though earlier reports referred to DCM cases dating back to 2014, we learned from this update that there were only seven reports regarding DCM made to the FDA from 2014 through 2017: one in 2014, one in 2015, two in 2016, and three in 2017.

But in 2018, the FDA received a communication from a group veterinary cardiology practice in the northeast concerning an unusual cluster of cases of DCM. The veterinarians reported that they had seen a number of dogs with DCM who were 1) not breeds known to be at a higher inherited risk of DCM, and 2) most had been eating grain-free diets prior to diagnosis.

Veterinary cardiologists discussed this with colleagues. Soon, other practitioners realized that they, too, had seen more cases of DCM in dogs of atypical breeds for the condition – and many of them, too, were eating diets that were grain-free and/or high in legumes and/or potatoes. More and more veterinarians started submitting reports about their patients to the FDA.

The FDA released its first advisory about this issue in July 2018, in order to alert pet owners and general-practice veterinarians of the possibility for DCM to develop in dogs, especially if they had been maintained on grain-free/legume-rich diets for any significant period of time. The agency warned interested parties to be on the lookout for the symptoms of DCM: loss of appetite, pale gums, increased heart rate, coughing, difficulty breathing, periods of weakness, and fainting.

This news almost immediately triggered a spike of cases being reported to the FDA. Some 320 reports of DCM were made in 2018; so far in 2019 (through April 30, the most recent date included in the FDA advisory update), some 197 reports of DCM have been made. Of the 560 dogs discussed in these reports, 119 have died.

The FDA cannot confirm, however, whether these numbers indicate an actual increase in the population of dogs that develop or die from DCM or whether the attention brought to bear on this issue has increased awareness and hence reporting; unlike in human epidemiology, rates of disease and deaths are not kept for animals. (FDA: “Because the occurrence of different diseases in dogs and cats is not routinely tracked and there is no widespread surveillance system like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have for human health, we do not have a measure of the typical rate of occurrence of disease apart from what is reported to the FDA.”) Because we don’t know what the rate of DCM is overall, it’s possible that many cardiac problems, diet-related or not, have gone unreported or even undetected (for example, mistakenly attributed to “old age”) until the FDA advisories and updates brought it to the attention of many dog owners.

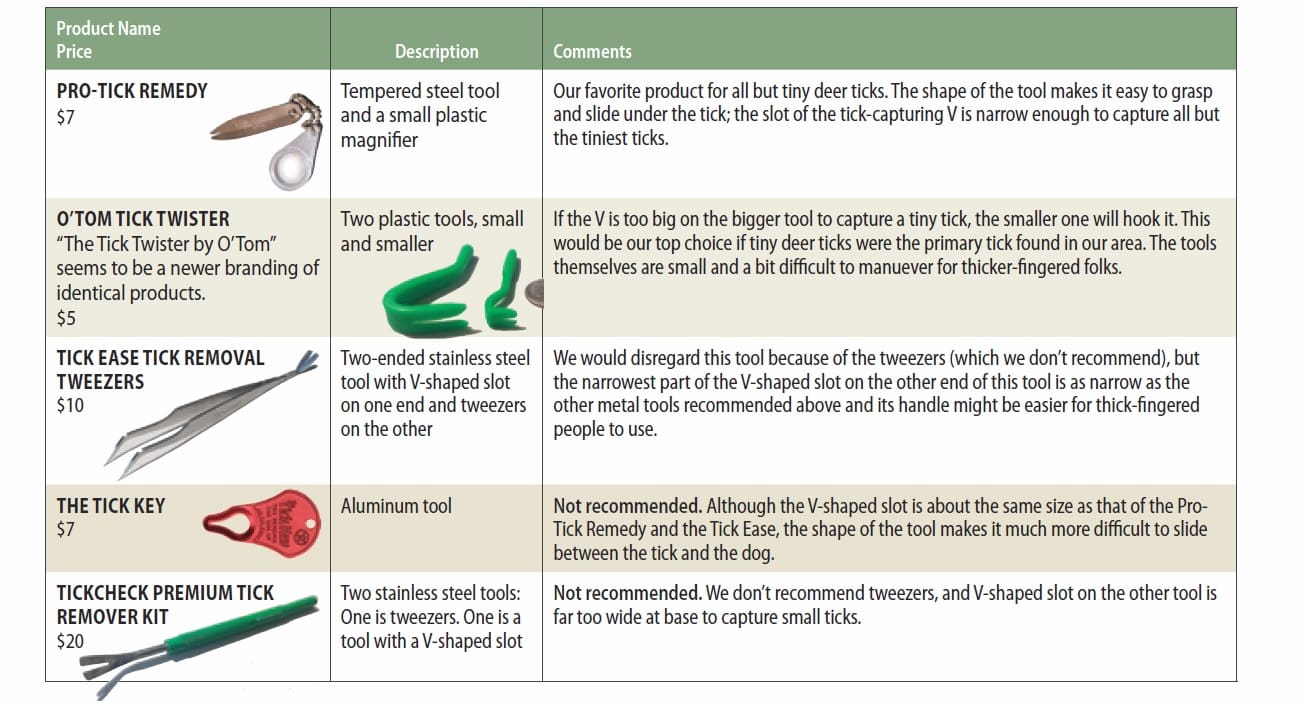

One of the major points made in the 2018 advisory was that cardiologists were seeing the unexpected development of DCM in atypical breeds and in dogs with other atypical characteristics. DCM tends to affect dogs of certain breeds (most of which are large and giant breeds), older dogs, and more dogs who are overweight than of ideal or low weight. Veterinary cardiologists say they are seeing more cases in breeds that are not known to have a genetic predisposition to DCM, in younger dogs, and in medium and even very small dogs.

The FDA’s 2019 update confirmed that there has been, at a minimum, a shift in the makeup of the dogs involved in these 560 cases. The update contains a table that enumerates how many dogs of various breeds are represented in the 560 cases. The breed with the most cases (95) is the Golden Retriever. However, according to registration numbers of purebred dogs, it’s the third most popular breed in the U.S. Also, the FDA has speculated that there has been greater awareness and social media discussion about DCM among Golden Retriever owners (as they are prone to a taurine-responsive form of DCM), and this perhaps prompted Golden owners to bring their dogs to the vet and be diagnosed sooner, and to report their cases to the FDA.

Mixed-breed dogs are next on the list with 62 cases, then Labrador Retrievers with 47; in neither case would those dogs be expected to have a genetic predisposition to DCM. There are more mixed-breed dogs in the U.S. than any individual pure breed, and Labradors are the most numerous purebred dog in the U.S., so it may be that these dogs are represented so high on this list by virtue of their greater representation in the population. Fourth on the list, though, is a breed that is known to have a genetically higher risk of DCM: Great Danes, with 25 cases. There were 23 pit bulls, and then two more breeds known to be at higher risk of DCM: German Shepherd Dogs (with 19 cases) and Doberman Pinschers (15).

DCM tends to affect more male dogs than females, and that pattern has held, with 58.7% of the cases involving males. This, as well as the atypical age and breed distribution of the cases, had led FDA researchers to surmise that the cases that have been reported to them this far are the result of a combination of expected causes (inherited predisposition) and dietary causes.

The implicated companies

Again, it’s a little weird that the FDA named pet food companies, when the link between the foods and the cases of DCM is not yet clear. Even stranger is that they named only 16 companies – that fact seemed to make the biggest impression on the mainstream media. Headlines in publication after publication make it sound like there are just 16 companies that have been doing something wrong –making it sound as if as long as you avoid those companies when buying your dog’s food, all will be well. If only!

The 16 companies named by the FDA appear on a table presented in the update (linked again here, scroll down). The table lists the 16 companies that were named in 10 or more of the cases of canine DCM reported to the FDA since 2014. These 16 were implicated in 431 of the cases; the foods that were fed to the pets in the other 129 of the cases were not in the table – which leaves open the possibility that someone feeding a food that caused, say, nine cases, remains unaware that their dog’s food, too, may potentially contribute to their dog developing DCM. It’s a tad random.

The companies mentioned in every single one of the 560 cases are available, but not in a particularly accessible way. A link provided in the update takes the reader to a 77-page table that lists all known information about each DCM case presented to the FDA. We plan to mine that 77-page table for all this information – the companies named in fewer than 10 cases, as well as the varieties mentioned in every case – in the weeks ahead. We will share it with you when we’re done – or share a link if someone does this and posts the information before us.

Also, the update did not specify which varieties of each company’s products were implicated. While some of the companies named make only the type of products that have been implicated in the majority of reports (we will get to that in a minute), some of those 16 companies make two types of products: the type that has been implicated in the vast majority of the 560 cases, as well as products that contain grain and do not contain any of the ingredients that seem to be associated with the development of DCM. In the case of these companies, naming only the brand and not the varieties implicated in the reports was a disservice to the companies and consumers alike.

Characteristics of the implicated foods

The FDA has not yet reached any conclusions about definitive links between the foods that the 560 dogs were being fed and their development of DCM. However, if, in an abundance of caution, an owner wanted to avoid products that share the traits of these foods, it’s possible to do so. The update includes enough information about the implicated foods that could help consumers select foods that do not share the traits of the implicated foods. Just keep in mind that causation is still unknown and that the FDA’s only conclusion so far is that “DCM in dogs is a complex scientific issue that may involve multiple factors.”

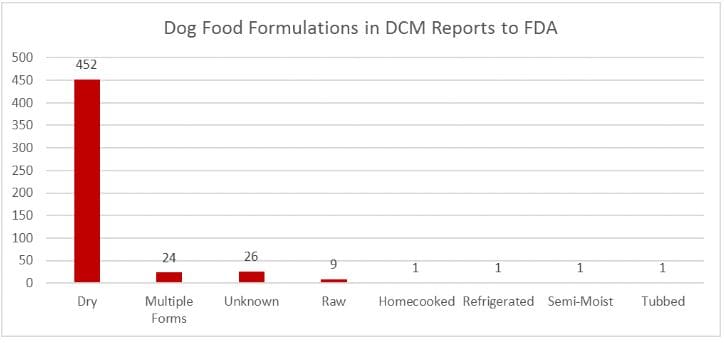

The vast majority of the products that the owners were feeding to the dogs in the reports submitted to the FDA were dry dog foods: 452 of the 515 reports involved dry dog food. The thing is, 452/515 is 88%. Currently about 85 to 90 percent of owners feed dry food, so this proportion is probably equal to the proportion of healthy dogs who are fed dry diets, so (statistically speaking) is meaningless information.

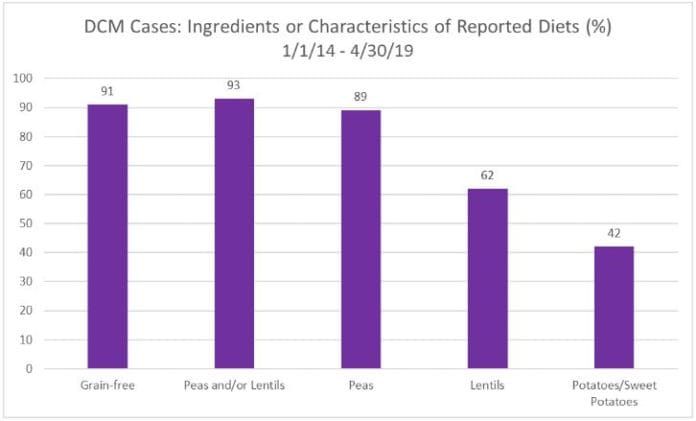

Grain-free diets represented 91% of the products implicated in the reports; 93% contained peas and/or lentils. Potatoes and/or sweet potatoes were present in 42% of the products. These numbers are far more intriguing.

The inclusion of peas, lentils, chickpeas, and other legume seeds have reached some sort of critical mass in recent years with pet food manufacturers. Though they’ve been present in many pet foods for at least a decade, in recent years, the percentage of their representation in formulas has grown. We wouldn’t worry unduly about one of these ingredients appearing on an ingredients panel in a minor role – 6th or 7th or lower on the list, say. But if there is more than one of these ingredients on the list and/or one in one of the top five or so positions on the ingredients list, for now, we’d look for another product to feed our dogs.

There are a number of animal nutrition experts speculating about what might be happening with these foods and why some dogs who have been eating them have developed heart problems. We will follow up with some analysis of some of the leading theories in future posts, but for now, let’s focus on what owners can do immediately to protect their dogs, based on what is currently understood and/or suspected about the relationship between the foods named in the reports made to the FDA and the dogs’ health problems.

Our recommendations for action

1. As we stated in our response to the 2018 advisory a year ago, no matter what your dog eats, if she has any signs of DCM – including decreased energy, cough, difficulty breathing, and episodes of collapse – you should make an appointment to see your veterinarian ASAP, preferably one who can refer you to a veterinary cardiologist.

2. For now, we would strongly recommend avoiding foods that use peas – including constituent parts of peas, such as pea starch, pea protein, and pea fiber, and especially multiple iterations of peas (such as green peas, yellow peas, pea protein, etc.) as major ingredients. If any one of these appears higher than the 6th or 7th ingredient on an ingredient list, for now, we’d switch to foods that do not display this trait.

Same goes for chickpeas (may be referred to as garbanzo beans), any other type of bean, and lentils.

We’d switch away from any foods containing more than one of these ingredients (peas, beans, or lentils).

3. Also, if you read through the 77-page table that includes every one of the 515 reports received by the FDA about a pet with DCM, you will see many times over that pet owners fed whatever they had been feeding to their dogs for months or even years. The same food, day in and day out. Month in and month out. Year in and year out! We’ve said it before and we will say it again: Feeding the same food for months on end amounts to putting your dog’s life in a single company’s hands. Is there any company on earth that you would trust to provide ALL the nutrition you consume for the rest of your life?

Please switch foods frequently, and not just from one variety to a different variety made by the same company. Switch among products that are made by different companies, with different ingredients. Unless your dog has a proven allergy to a number of ingredients, switching from one food to another, as often as every time you buy a new bag of food, helps provide your dog with “balance over time,” and keeps any nutritional imbalances, overages, or deficiencies from contributing to your dog’s health problems.

4. As we have stated many times, we would feed grain-free foods ONLY to dogs with a demonstrated allergy to or intolerance of grains.

When grain-free dry dog foods were first introduced to the market, we were happy that owners of dogs who had a proven intolerance of or allergy to one or more grains could find commercial dry food options. However, as this segment of the market exploded, it became apparent that many more owners were choosing these products than dogs needed them. Somehow, the message spread among dog owners that grain-free foods were “better” – with little or no explanation offered as to why this was alleged. We based our concern about their over-popularity on the high levels of inclusion of ingredients that did not have a long history of use in dry dog foods. Potatoes and sweet potatoes worry us less than peas, chickpeas, and beans; they have been utilized in dry dog formulas for longer than the legumes.

What if your dog absolutely can’t consume ANY grain (and this has been demonstrated with a sound food allergy trial)? There are a number of companies whose grain-free foods do not appear or appear very infrequently on the 77-page table of all the DCM reports. We are aware that some dog food manufacturers add supplemental taurine to their products (and have always done so). Whether this or some other factor (ingredient sourcing, better manufacturing, better formulation, etc.) is responsible for their scarcity on that list, no one knows for sure. But if your dog absolutely can’t consume ANY grain, we’d look for products without peas or legumes (or those with perhaps ONE of these ingredients low on the ingredients list), from a manufacturer whose name is not found on the table… and to hedge your bet, we’d check to see whether they add supplemental taurine to their formulas (and go with one of their products if they do).

Not all of the dogs in these reports have been found to exhibit low taurine levels – and none of the diets implicated in the reports have been found to contain levels of the amino acids that dogs use to manufacture the taurine they need (cysteine and methionine) that fail to meet the current levels legally required for a “complete and balanced diet.” However, there are several compelling possible reasons that could result in the dogs’ failure to utilize or benefit from these amino acids. For example, some chicken meals are so low in digestibility – and often so heat-damaged – that the methionine is not present in an available form. Also, high fiber levels can interfere with some dogs’ ability to convert these amino acids into the amount of taurine they need. The main point is, there are dogs who have shown improvement after their diets have changed and supplemental taurine was prescribed.

Note: The possibility has been raised that there may be more than one mechanism at work causing all these DCM cases and cases of other cardiac problems, something to do with the cysteine /methionine/taurine issue and something else. While the vast majority of the implicated diets mentioned in the FDA’s reports are dry, grain-free foods, some food that do contain grains also have been implicated, as well as some canned, raw, etc. diets. All owners need to be alert to their dogs’ symptoms – and don’t just chalk up exercise intolerance, panting, lethargy, etc. to “old age” in previously healthy senior dogs! Make an appointment and discuss these symptoms with your veterinarian soon.