See that dog surfing your counter as you read this? You know, the one who jumps on you during your Zoom calls? That’s your ticket to 2020 happiness. The opportunity to “quarantrain” your furry friend – whether a new “pandemic pup” or your long-time pet – is one of the most positive ways you can direct your energy right now.

Dog training is more fun, and dramatically more effective, when it doesn’t have to be shoved into an inconvenient, stressed-out window of time. Those of us lucky enough to have a “new normal” that features being home a lot in stretchy pants have a golden opportunity – a chance to use our household routines to prompt a handful of simple one-minute sessions throughout the day.

Try it! This is a huge silver lining to grab from this pandemic. It’ll hardly feel like you’re doing much, but a month later, you will have an utterly transformed relationship with your dog, an addictive new hobby, and some unexpected moments of delight in your house.

THE SECRET OF DAILY REINFORCEMENT

Want to know why quarantraining works so well? The answer is in “sit.” Everybody’s dog knocks it out of the park when it comes to “sit.” Unfortunately, for many dogs, that’s about it. “Down” is a blank stare. “Stay” is anything but. And as for lying calmly on a mat while somebody’s cooking? Forget it.

Why, then, is “sit” always a solid skill?

Here’s the key: It’s the one thing that all owners work into their daily routine. Every single time they feed the dog, they ask for a sit first. Dog does behavior A; dog gets reward B. Reinforcement each time, 365 days a year. That makes for a rock-solid behavior.

Quarantraining finally gives you a chance to naturally apply that same approach to a host of other cues. You can create an association in your dog’s mind between things you do every day and behavior that they can be rewarded for, so that your daily movements become cues for canine behaviors you enjoy. A month from now, report back about the new way your calm dog is gazing at you, and how you’re cracking up while you text videos of your dog’s new tricks to your friends.

CUP OF COFFEE & “DOWN”

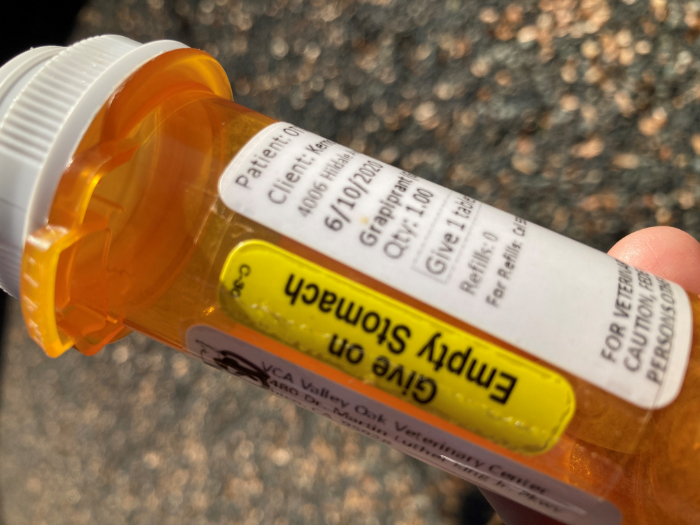

How many times do you pour a cup of coffee, juice, or water each day? How many times does your dog pad after you, ever hopeful that you might be getting a snack out of the fridge, one you might share with him? Here’s how to turn that habit into an easy training win.

Keep a cute ceramic container of your dog’s kibble or treats on the counter. Every time you go into the kitchen to fill your mug or glass, lure your pup into the down position with a piece of kibble or treat. In a week, your pup will be throwing a fabulous “down” every time you venture near the treat jar, which will make you laugh and exclaim, “Yes! What a good dog!” Now the “down” is just as strong as the “sit,” and you’re on your way.

BREAKFAST & “WAIT”

You’ve already got the nice sit before the dog bowl. How about adding a “wait” cue? Your pup is sitting, and you’re holding the bowl. You say “wait,” and pause a second or two while pup holds that sit, then put the bowl down: “Okay!”

After a week of taking just seconds to focus on this each day, you will have taught an incredibly helpful cue to your dog. Now you can take that “wait” out for a spin. Each day will hand you a dozen opportunities to ask for a “wait.” Practice it when your pup is about to barge out the door, shove through the gate, launch into the car, or careen onto the couch. Your pup still gets access to those things, but now they come as a result of heeding your cue.

Guess what happens after a month of that non-official training? You can add “wait” to the solid column. What’s more, you’ll have fewer of the micro-frustrations that were sneaking into every day at home.

DINNER & TRICKS

For pup’s dinner, you could also practice the sit and wait. Or . . . you could use that time to teach and practice something else. How about asking for a shake before the bowl goes down? Or a spin? Or how about eventually developing a little routine? Perhaps a spin-sit-shake-down-wait, then the bowl?

The result? Smiles for the entire family, daily. Again, a nice upward swing in the psychic feel at home. Somehow this pup just gets cuter and cuter!

TOO MUCH SCREEN TIME? WORK ON SOME RECALLS

Any chance anyone’s family is spending way too much time in front of screens? How about playing a fun, raucous game – outside, if you can – every night after dinner for 10 minutes? Load up with something yummy, cut into tiny pieces. (Tonight’s leftover chicken? Cheddar cheese?) Split the treats between all of you, get into a big circle, and call your pup back and forth between you. She gets one delicious nibble whenever she runs to the person who just called her. So simple. So effective.

More often than not, owners fail to actually practice the recall cue. But they sure use it! They use it to call their pup away from all of the fun stuff – the dog park, the neighbor’s yard, the deer they’re chasing. All that does is turn that cue for “come” into something your dog is sure to ignore.

But if you take 10 minutes every night to play this game with happy voices, lots of cheer, and always the very best treats, suddenly that word is going to perk up your pup’s ears when it counts. It just might save her life one day.

ZOOM CALLS & “PLACE”

It’s like clockwork: the second the Zoom meeting starts, the dog is pawing at your elbow. You push her away, and she jumps up on your thigh. Your colleagues were amused when this was new. It is no longer new.

This is a golden opportunity to teach “place.” Put a mat near your desk. The first day, every time you see your pup go near that mat, toss a piece of her kibble or a treat on it. She will start hanging out near the mat more. Once she does, toss the treat only when she actually steps on the mat, then only when she stands completely on the mat, and finally only when she lies on the mat. Once she’s reliably doing that, call it “place.”

Eventually, when you start a Zoom call and she paws at you, you can say “place” and she’ll know the most rewarding spot she could be in at that moment is her mat. Want to make that behavior rock-solid? Put another mat in the kitchen. Practice “place” every time you cook, or sit down to eat a meal.

Gosh, she’s starting to seem like such a well-behaved dog, isn’t she? Like a movie dog. Now the whole family is looking at her lying there, and suddenly feeling really lucky. What a nice thing to feel in 2020.

BATHROOM & “STAY”

Does your dog follow you around the house all day? Like . . . all day? It’s okay. You can admit it: You always have company when you go to the bathroom. Let’s turn that into some multi-tasking!

If your dog has a beginning “stay” where you can step just a foot away for a moment, this is a perfect opportunity to turn that into a stay you can ask for when the relatives are unloading the food for the holiday and the gate is wide open!

Once again, we prep by keeping a little jar of treats on the counter. As you approach the bathroom doorway, turn around and ask your dog for a “down.” Reward with a treat, and ask for a “stay.” Step a foot into the bathroom, then come right back and reward. Repeat a dozen times over the next few days until pup has the hang of lying in a stay at the threshold to the bathroom.

Now you’re ready to use it for real. Have to use the bathroom? “Stay.” Pup now knows each of these moments is a chance to get a treat, just by lying quietly at the door.

Once you get to a very solid indoor “stay,” you’ll be ready to make the most of the everyday walk to the mailbox! Clip a long line to your pup’s collar, and ask her to stay in a down on your front step. Then take a few steps out toward the mailbox, but come right back and treat. Then do it again, but go a bit farther. Repeat until you can go all the way to the mailbox and back, giving pup a great treat each time she keeps that stay until your return.

See how this is way more fun, for both you and the dog, than just shoving the door shut in her face and trudging out to the mailbox? Dog training = happiness.

DOG TRAINING AS A WAY OF LIFE

Most people vaguely think they might train with their dogs if only they had the time. The thing is, how much time does it take to ask for that “sit” before the food bowl? Right.

That’s the secret to quarantraining. With a tiny bit of preparation and intention – but very little time – you’ll discover you and your dog can do amazing things together. Just try it and see! There’s so much ahead for you both.