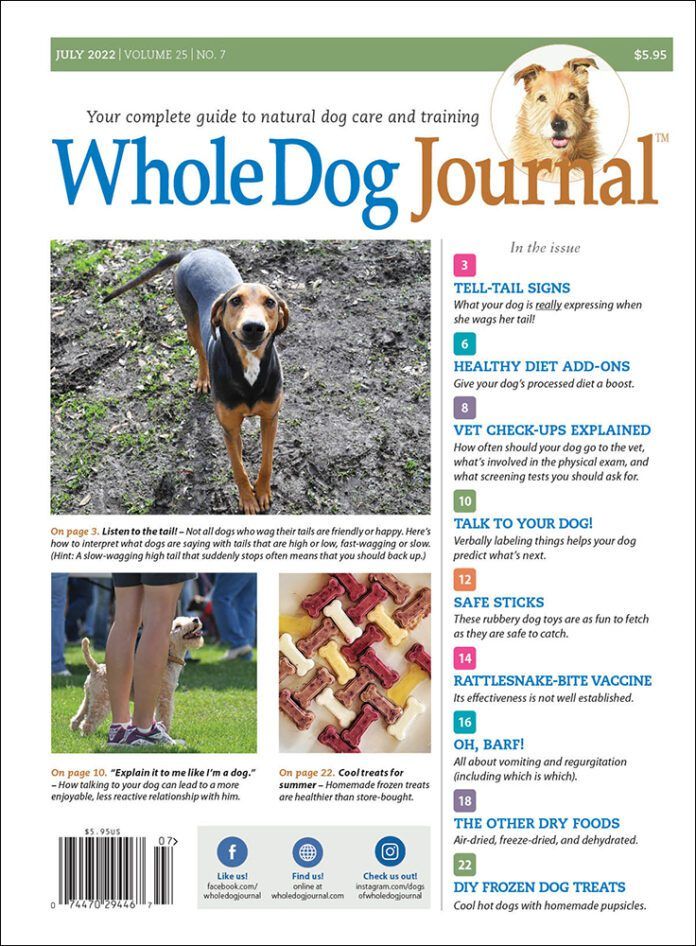

- Tell-Tail Signs

- Healthy Diet Add-Ons

- Vet Check-Ups Explained

- Talk To Your Dogs

- Safe Sticks

- Rattlesnake-Bite Vaccine

- Oh, Barf!

- The Other Dry Foods

- DIY Frozen Dog Treats

Download The Full July 2022 Issue PDF

Leaving town? Make sure a “go bag” is available to your pets’ caretaker before you leave!

Last week I attended a conference out of town (it was put on by the Shelter Playgroup Alliance, very cool stuff). For several reasons, I brought Boone, the latest addition to our family (my husband is fine with taking care of our adult dogs, but he’s a little inattentive for the constant supervision required for destruction prevention by a five-month-old puppy, and also, because my go-to puppy-sitting friend attended the conference, too!). Boone handled himself like a champ and benefitted from a lot of terrific socialization opportunities from a very educated, dog-friendly group of people.

Here’s the one thing that stopped my heart for a minute: Receiving a text from a friend that said, “Doing ok? Fire.”

You’d have to be living under a rock to be unaware of the fact that the entire Western U.S. is experiencing a years-long drought, which has been contributing to longer and ever-more destructive wildland fires. Historically, the so-called “fire season” in California has been considered to be about July through October. But it seems to start earlier every year and last longer; the devastating Camp Fire of 2018 (located in my county) started on November 8! This is the fire that seared onto my brain the need for pet owners to prepare for emergencies (I wrote about my experiences helping evacuated animals here, here, and here.)

When I’m home, I monitor various new sources for any alerts about fires in my county, not only so that I can respond appropriately to a fire in our immediate area, but also so I can respond quickly to serve as a volunteer for the emergency animal response organization in our area (the North Valley Animal Disaster Group [NVADG]). I follow Cal Fire and several of its local sub-accounts on Twitter, starting with the one that serves my area, Cal Fire Butte Unit. There is also a Facebook page, Butte Wx Spotter, that quickly posts any sort of fire, flood, or another environment-based disaster in my area.

But when I’m at a conference, I don’t look at my phone nearly as often, so I didn’t see any of these pages lighting up with news about a fire that started less than 12 miles from my home. Ack! Twelve miles is nothing in a strong wind-driven fire. 2020’s North Complex fire traveled more than 20 miles in a few hours, prompting our evacuation at 11 pm.

Fortunately, because I do follow all of those sources, I was able to quickly ascertain that while the fire was relatively close to my home, Cal Fire responded quickly and forcefully enough to squash it within a few hours.

The event has put me on full alert for the rest of the summer – and hit me over the head with a reminder that I had not prepared a “go bag” that would have been accessible to my husband had he needed to evacuate from our property with our two adult dogs. I know from past experience, both as a person who has had to evacuate from our property in the middle of the night due to a fast-moving fire, and as someone who volunteers with NVADG caring for pets who were evacuated from other fires, that having a go-bag ready to grab at a moment’s notice can make a huge difference to one’s peace of mind in case of an evacuation. For example, if my husband had to evacuate with our dogs, but left Otto’s pain medications behind, our poor old guy would be in serious discomfort until we could get refills. If we had to board the dogs somewhere because our house burned down, or show proof of vaccination to stay in a shelter, and didn’t have the dogs’ vaccination records, we’d be stuck (especially if, as in the case of the Camp fire, many veterinary and doctor offices burned down, too, leaving people with NO health records at all!).

If I was home, I could have put the 2022 version of the go bag together in a few minutes – but explaining to my husband where everything was would have been ridiculously complicated. Lesson learned. Now that I’m safely home, I’ve put that together and showed my husband where it’s located.

What should be in your dog’s “go bag”? At a bare minimum, it should contain at least a few days’ supply of any medications he takes or might need in a high-stress situation, and copies of his vaccination records. If your dog becomes anxious in cars or in new situations, and you have a prescription for a sedative medication, I’d keep some of that medication in the go bag as well. You can also include extra collars, leashes, ID tags, and bowls, and perhaps a few cans of food (less perishable than dry food). The go bag is a great place to store your pet-first-aid kit and your dog’s muzzle if he’s a bite-risk in chaotic situations and you’ve already habituated him to wearing one.

Fires are the biggest threat in my part of the country, but floods and tornadoes are reasons for quick evacuations elsewhere. Consider this my annual reminder to GET READY!

For more information on emergency preparedness, see:

https://www.nvadg.org/how-to-be-ready-to-evacuate-with-pets/

https://www.readyforwildfire.org/prepare-for-wildfire/go-evacuation-guide/animal-evacuation/

https://www.aspcapro.org/resource/travel-bag-download-pet-evacuations-plus-disaster-shareables

https://www.americanhumane.org/blog/this-june-prepare-for-your-pets/

Can You Register Your Dog as a Service Dog?

Calm, cool and collected; attentive and disciplined — surely those admirably trained service dogs who assist disabled people must complete a stringent certification and registration process, right? Actually, and perhaps surprisingly, no, service dogs don’t have to be certified or registered.

Service dog regulations are codified in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which requires no certification or registration of any kind. Sure, you can pay for a certificate or a registration — plenty of private online entities are happy to sell you that piece of paper — but it carries no weight, no legal standing. The ADA states, “These documents do not convey any rights under the ADA and the Department of Justice does not recognize them as proof that the dog is a service animal.”

In fact, the ADA defines a service dog simply as “a dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for an individual with a disability,” and the task (or tasks) must be directly related to the disability. Examples of service dog tasks are numerous, and a few are:

- a dog taught to retrieve emergency medication to hand when her owner needs it

- dog trained to guide a person safely across the street

- a dog taught to alert a diabetic to dangerous blood sugar levels.

The ADA definition of a service dog is concise but highly inclusive. Let’s say you’re physically impaired from being able to pick up objects off the floor, so you’ve trained your dog to retrieve those objects for you. Provided she is perfectly behaved in public, you have yourself a service dog — congratulations!

There is no official list of qualifying disabilities for engaging the aid of a service dog, and dogs are trained to assist in an extensive range of physical and psychological challenges. And when it comes to that training, yes, service dogs require both exceptional training and superb aptitude, but the ADA mandates no specific training protocol. You or a family member or a friend can train your service dog, or you can pay a professional trainer (they are ubiquitous, but given the expense, vet trainers thoroughly).

The ADA service dog definition excludes emotional support dogs, therapy dogs and companion dogs because they have not been trained to perform a task specific to the owner’s disability.

Critically, the ADA provides the legal footing for service dogs accompanying their owners in virtually all public settings and venues. The only requirements are the service dog must be fully trained and under the complete control of its handler and the dog does not need any special form of identification, such as a service dog vest. The ADA also specifies that staff at public places can ask only two questions of a service dog’s handler:

- “Is the dog a service animal required because of a disability?”

- “What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?”

Generally, a service dog can only be excluded from accompanying its human handler if the dog’s presence would “fundamentally alter the nature of a service or program provided to the public.” Some states and municipalities may allow in-training service dogs, or even emotional support dogs and therapy dogs similar leeway, so check local laws.

How Long Are Dogs Pregnant For?

With the exception of dog breeders, many dog owners will have little experience with pregnancy in dogs. It may surprise you to learn that, while human pregnancies typically last around nine months, the dog gestation period is much shorter, averaging just nine weeks or 63 days. Since the pregnancy period is so short, each day matters that much more. Dog owners must be able to recognize the stages and signs of dog pregnancy to provide the best possible care for the expectant mother and pups along the way.

Signs of pregnancy in dogs

If your dog has been spayed, there is no chance she will become pregnant. However, intact female dogs typically go through heat around every six months during which they may become pregnant. When your dog will go through heat does vary with different breeds with some dog breeds only going through heat once a year. Check with your dog breeder or the dog breed national parent club to find when your dog is most likely to go into heat. There’s currently no instantaneous dog pregnancy test like humans have, but there are certain signs of which to be aware. Note that most dogs won’t show clinical symptoms during the first few weeks of the pregnancy (gestation) period.

Here are five signs of pregnancy in dogs:

- Weight gain

- Increase in appetite

- Swollen belly

- Enlarged nipples

- Increased affection seeking

Once you suspect your dog may be pregnant, bring her to your veterinarian as soon as possible. There, a vet can perform diagnostics including palpation (feeling the abdomen for swelling), hormone tests, X-rays and ultrasounds to confirm a dog’s pregnancy.

Care during a dog’s gestation period

Since canine pregnancy lasts just nine weeks, it’s imperative to monitor your female dog closely during the dog gestation period. This will help you catch any irregularities or possible complications as early as possible. You should also consult with your vet early on and visit regularly as your dog’s pregnancy progresses. Having a plan in place for the birthing of puppies will help you be better prepared for the big moment.

Feed pregnant dogs a high-quality diet, with no changes to normal food intake during the first two-thirds of the gestation period. After six weeks of pregnancy, slowly increase food intake to keep up with the growing mother-to-be. Omega-3 fatty acids are vital to developing puppies, so consider a supplement if you think your dog’s diet could use a boost.

Lastly, prepare as best you can for puppies with a whelping box and any other necessities for a smooth birthing process. Dog pregnancies can be a whirlwind and nine weeks goes by fast. If you follow the right steps, your pregnant dog will soon be the proud parent of a litter of happy and healthy puppies.

Keeping the puppy: The new normal

The news that I’m keeping my former foster puppy is leaking out. I loved him from the get-go, when I agreed to foster him for my local shelter, back at the beginning of March. The reason I didn’t just immediately decide to keep him was that I wanted to give my senior dog, Otto, extra consideration. No old dog should have to spend his or her last days being harassed by a rambunctious puppy – or perhaps a slightly disrespectful one.

But as it turns out, though 14 ½-year-old Otto doesn’t particularly like Boone (the new puppy’s name), he doesn’t seem to mind him, either. He mostly ignores most other dogs, just as he did with Woody, my six-year old dog, when he was a puppy. The difference is, Boone has another playmate: Woody! As much as Otto ignores Boone, Boone ignores Otto, and focuses all his love and mischievousness on the younger dog.

The one time Boone and Otto are ever proximate is when I work with Boone on good-manners behaviors. As soon as Otto sees someone getting treats for sits, downs, or stays, he comes a-running to get in on the fun. When he was younger, he’d be the first to hit the floor on the “sit” and “down” cues, like the smarty-pants kid, jumping out of his chair to raise his whole arm, frantic to let the teacher know he knows all the answers to all the questions the teacher asks the class. Today, he crashes our “classes” to demand treats – but often doesn’t even bother hitting the sits or downs! He’s playing the “senile old man” card a lot – and, because of his arthritis, I let him get away with it, most of the time. As long as he waits his turn and doesn’t interrupt the pup’s learning, he “earns” many treats for just being his usual handsome self.

As this spring warms into summer, Otto spends most of the day in his shady sandbox, which we keep nice and damp for him. He’s been insisting on spending a lot of his nights out there, too. I’m not crazy about him being out all night – especially since we have coyotes and even mountain lions in our neck of the edge-of-town woods, but if I’m to get any sleep whatsoever myself, I have to give in and let him go outdoors. Otherwise, starting uncannily close to 2 a.m. every night, he will pace and pant and escalate into whining and even barking, insisting to go outside. If I let him out and make him come right back inside after relieving his bladder, I will get maybe an hour’s peace before he starts with the pacing and panting all over again. This is torture for me; I start feeling crazy with lack of sleep myself! So I give in, and he gets to stay outside – usually until around five a.m., when he’ll bark to be let back in.

I do have an outdoor pen that I could lock Otto in. He’d be outdoors, but protected from any potential predators. But no; that’s not his jam. I’ve tried it, and he just barks in protest. He knows how to accept being locked in the pen and wouldn’t dream of barking rudely during the day, but at night, he’s a different and fairly unreasonable old dog. He wants to be out patrolling the property (or surveilling from the sandbox). He’s going to make us all miserable if he doesn’t get what he wants at night. So he gets it, as scary as this is for me.

Boone and Woody sleep right through all of this letting Otto in and out. Thank goodness! If we had one more insomniac in the house, I don’t know what I’d do.

During much of the day, Boone shadows Woody, his idol. He sleeps with Woody (often, on Woody), and takes his cues about what to do when they see people passing our house from Woody (run to the fence, barking, and then run back to me, wherever I am, for treats!). He brings toys to Woody, inviting play, and when Woody isn’t interested in playing tug or chase games, he’ll kill time by laying on or near the big dog and chewing very gently on Woody’s ears! It’s the weirdest thing! Woody lets him do it; these days, his ears are almost always a little crunchy with dried Boone saliva.

Boone does spend a little time on his own, exploring our property. He likes to play with a toy I’ve hung from the bottom of my grandson’s tree swing; he’ll grab the toy and run with it as far as the rope will go, and then turn and tug furiously, lifting his front feet off the ground, then dropping it and watching it swing away from him, chasing it, and starting all over again.

He also plays this game with the tree on our front lawn. My husband doesn’t like the willow-like hanging branches, so we allow him to go ahead and do a little trimming.

Here’s a video of Boone playing with the trees.

I make Boone spend a little time in the outdoor pen during the day. It’s where he gets to enjoy chewing on pizzles, licking toys stuffed with canned food and frozen or Lickimats slathered with peanut butter. He’s doing great with these short (maybe an hour-long), daily confinement/alone-time practice sessions.

It’s definitely harder to give each one of my three dogs individual attention, and I think maybe it’s Woody who is getting the short end of the stick. Because Boone adores him so much, he is forced to babysit, and while he clearly enjoys having someone to play with sometimes, at other times, he looks sort of glum. I imagine he’s saying, “When is this twerp leaving?” When that happens, I call my friend Leonora, to see if Woody can visit her and her little dog Samson, and enjoy some spoiling time free from puppy spit.

It seems to be working out.

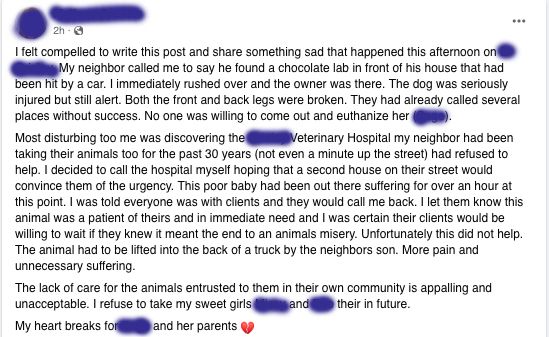

Please, use pet-related social media for good, not blame and slander

I follow three or four local “lost and found pet” groups on Facebook. These are places where people in the community can post photos of dogs they’ve lost or found, and where neighbors can come together in the comments to offer suggestions to both distraught owners of lost dogs or overwhelmed dog finders. These sites can be invaluable for reuniting pets and owners, as members tend to be the kind of people who pay attention and remember any stray or needy animals they’ve seen.

When I have found a stray dog, it’s helpful to already belong to these groups, so I can quickly submit a “found dog” post. Usually, nonmembers of these groups can’t post to them; generally, you have to wait for a moderator to approve of your membership in the group before you can post – and sometimes it takes a moderator a day or more to respond to your request to join the group! As an already-approved member of these groups, I’ve had responses that helped locate the owners of the dog or dogs I found within an hour!

That’s the good news. The bad news is that these groups can also be a place where people with animal-related problems blame others in the community for those problems, look for other people to solve their problems for them, and bash anyone in the helping professions who fail to help. Animal control officers who fail to materialize immediately, shelters that are overcrowded, and veterinarians who fail to go to any lengths to save the lives of injured stray animals often get singled out for shaming and blaming. I try hard not to read those posts – and have to try even harder, sometimes, to not to respond to them!

Well, I failed utterly the other day. Here was the post that caught my eye:

The post reads:

“I felt compelled to write this post and share something sad that happened this afternoon on XXXXX Road. My neighbor called me to say he found a chocolate lab in front of his house that had been hit by a car. I immediately rushed over and the owner was there. The dog was seriously injured but still alert. Both the front and back legs were broken. They had already called several places without success. No one was willing to come out and euthanize her (XXX).

“Most disturbing too (stet) me was discovering the XXXXXXX Veterinary Hospital (my neighbor had been taking their animals too (stet) for the past 30 years (not even a minute up the street) had refused to help. I decided to call the hospital myself hoping that a second house on their street would convince them of the urgency. This poor baby had been out there suffering for over an hour at this point. I was told everyone was with clients and they would call me back. I let them know this animal was a patient of theirs and in immediate need and I was certain their clients would be willing to wait 10 minutes if they knew it meant the end to an animals (stet) misery. Unfortunately this did not help. The animal had to be lifted into the back of a truck by the neighbors (stet) son. More pain and unnecessary suffering.

“The lack of care for the animals entrusted to them in their own community is appalling and unacceptable. I refuse to take my sweet girls XXXX and XXXX their (stet) in the future.

“My heart breaks for XXXXXX and her parents”

Within hours, there were more than 100 comments from people who were promising to never bring business to the named vet clinic and, what’s more, stating that they would be leaving the vet clinic a bad review.

I don’t know the veterinarian at that clinic personally, but I have a friend who takes all of her pets there – and my friend has encouraged me to bring my dogs there if my vets are ever unavailable, because even though this clinic is farther away than the clinics I currently patronize, my friend finds that the vet and support staff there to be uniquely kind and competent, and the wait times not bad. Through my friend (and a quick review of the clinic’s website to be certain), I’m aware that this clinic has one doctor working there. And now there are hundreds of people in our community being told that this doctor is heartless and inhumane, because she didn’t leave her patients on a moment’s notice in order to run down the street and euthanize a dog on the side of the road. Argh!

Social media can do so much good, especially when it’s bringing people together to accomplish something for those in need. Why do so many people insist on using it for negativity?

Don’t wait to teach your dog cooperative care procedures!

I’ve taught both of my grown-up dogs several positions where they will be rewarded for holding still while I – or, importantly, a stranger such as a vet or vet tech – examines them. They both will lay flat and hold still, or stand and do a “chin rest” (where they press their chin in my hand) and hold still. But the desired behavior is not just “remaining still no matter what”; the “cooperative care” piece of this behavior is a sort of deal: they hold still so that I (or someone else) can touch and examine them, but if they lift their heads, the touching and/or exam must stop immediately. It’s the “deal” you make with them, and what I – like most people who teach this behavior – have found, is that once they learn that they have control over the procedure – they can stop the exam at any moment by lifting their head – they feel more confident about going along with it.

We explained and showed you how to teach cooperative care behaviors in “Cooperative Care: Giving Your Dog Choice and Control” (WDJ February 2021).

However, I’ve been remiss in working with Boone, the name we’ve finally given to the “foster puppy” who has been here since early March. (I guess this is also an adoption announcement!) Something I’ve observed about him since he’s been here: He hates people looking at his teeth!

Checking a puppy’s teeth before he’s 6 months old is the best way to estimate his age, as the “puppy teeth” all start falling out when the pup is around 4 months old, are usually all gone by about 5 months, and have all newly erupted incisors (the little front teeth), canines (the “fangs”), and premolars (the ones just behind the canines) by about 7 months. (The molars generally take a little longer to erupt, but this varies a lot by the size of the dog.)

Ever since was brought into my local shelter as a “stray,” people have been lifting his lips and trying to figure out his age. He was a lot larger and bigger-boned than the litter of 11 puppies that were brought into the shelter on the same day; the staff judged him to be about 8 weeks old, just based on size, but his demeanor and lack of coordination made him seem much younger. To try to get a better read on his age, shelter staff members (and I!) kept trying to look at his teeth – and he’d struggle every time! And every time, I’d say, “Oy! I have to work on that behavior!”

Now I’m paying the price for having not yet taken the time to work on it.

Yesterday, while wrestling and playing tug-of-war with Boone and Woody on our trampoline (a favorite place for this), I heard Boone screech when he and Woody’s mouths bumped as they jostled for the same toy. The next time in the game when he came to sit in my lap, I tried to gently put my hands on Boone’s muzzle, so I could try to see if he had something wrong – a wood splinter or plastic chunk stuck in his teeth, or a foxtail jammed in his gums, perhaps. He could even have a snake bite or something else really serious hiding under that adorable beard! But as I went to lift his lips, he screeched again and dodged away from me. Uh oh; something definitely wrong going on in there. Now I have to look, and we have no agreement or understanding about how this is going to get done.

This is one of those times when it would be easy to permanently damage my relationship with the pup, or advance his reluctance to have his mouth examined into full-scale aggressive resistance.

Instead, I spent more than an hour, in five-minute sessions over the course of the evening and well into the night, working with Boone to teach him a chin rest (that went very quickly – he got it almost immediately) and to hold that chin rest while I touched his upper lip. That made him a little frustrated, because he is very food-motivated, but he also does not want to tolerate any pressure on his upper lips at all.

As we practiced, I was able to determine that he didn’t have any obvious bite marks or wounds on the outside of his face, and given his ability to take treats and chew his dinner kibble, I surmised that he didn’t have anything seriously wrong with his mouth. I suspected – from our previous estimates of his age – that he lost one of those canines; it might have even been torn out during his raucous games of tug with Woody. So I didn’t push for a more complete exam.

But this morning, we went back to the drawing board, and after another half-dozen, several-minute sessions, I was finally able to get Boone to stay still and allow me to lift his upper lip enough to confirm my suspicion: He has a (relatively) big gaping hole where his top left canine used to be. The other canines are all still firmly in place, so he likely lost that one a little prematurely, leaving the gum very sensitive.

I’m glad that’s all it is – but I’m definitely going to commit to daily sessions of the cooperative care “Bucket Game” from here on out. I don’t want the next medical crisis to precipitate a behavioral one.

Bloat in Dogs Is Deadly

Stomach bloat is something that every dog owner should be aware of. Knowing the early signs of bloating in dogs and the best ways to prevent it can mean the difference between life and death for your dog, and a full or empty bank account for you.

The fancy medical term for simple bloat is gastric dilatation. The fancy medical term for severe bloat with a twisted stomach is gastric dilatation-volvulus, or GDV.

DOGS WHO ARE HIGH RISK FOR BLOAT

Really any dog (or cat) can bloat, but it is far more likely in large breed, deep chested dogs. The Great Dane is far and away the No. 1 breed when it comes to bloat. Other high-risk breeds include the Greyhound, St. Bernard, Weimaraner, German Shepherd, Boxer, and setter breeds.

Any large dog (over 90 pounds) should be considered at risk, and this risk increases with age. Interestingly, the Bassett Hound, though smaller, also has a greater than normal propensity to bloat.

CAUSES OF BLOAT IN DOGS

Nobody knows exactly what causes bloat or why it happens in some dogs and not others, but there are certain things that have been linked to an increased risk of bloating including:

- History of bloat in a particular breed line (hints to a possible genetic predisposition)

- Dogs who eat too fast (ingest excess air with the meal)

- Using elevated feeding bowls (promotes ingestion of excess air with the meal)

- Feeding dry food with heavy fat/oil content

- Feeding a large meal vs. multiple smaller meals

- Exercising on a full stomach

- Drinking excessive amounts of water at one time

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN DOGS BLOAT

If excess gas starts to accumulate in the stomach for whatever reason, the distension quickly kinks off both the entrance and the exit of the stomach, so there is no way for the dog to dispel the gas that’s normally accomplished by burping or passing gas through the intestines.

Additionally, the pressure from the gas compromises the blood flow to the stomach wall, which starts suffering tissue injury right away. Then the big gas-filled stomach starts putting pressure on the great vessels that return blood to the heart (these travel underneath your dog’s backbone), which compromises cardiac output and general circulation, throwing your dog into shock.

At a certain point, the gas-filled larger part of the stomach (the “body” of the stomach) starts floating upward and flips over, resulting in a twisted stomach. This compounds all the issues mentioned above and accelerates the speed of progression of this disastrous medical condition. Without emergency surgical intervention, dogs with GDV die a painful death from cardiovascular shock and septic peritonitis from stomach devitalization and/or rupture, and it can happen within hours.

SIGNS OF BLOATING IN DOGS

Bloating dogs usually appear uncomfortable, if not distressed. It comes on suddenly. They are restless and may pace. Drooling and panting are common. Their bellies sometimes, but not always, look distended, and they may react painfully to pressure placed on their left flank. It’s common for dogs to display frequent, unproductive retching like they are trying to vomit but can’t.

WHAT TO DO

Get to a veterinary hospital as soon as any suspicion arises. Time is of the essence! If your dog receives treatment early enough, twisting of the stomach may be avoided and the full snowballing, life-threatening process described above may be averted.

To have this surgery performed or not, that is the question. There are many opinions about this; it may just come down to what feels right for you and your dog.

Why wouldn’t you do it? Well, it’s a pretty major surgery to put your dog through when you don’t even know if he’ll ever bloat. There are risks (and significant cost) associated with any surgical procedure. And even if you have your dog ’pexied, it doesn’t mean he can’t bloat. It only means the stomach can’t flip. So you may still have some costly emergency visits for decompressing simple bloats if they occur.

Why would you do it? Maybe you’ve had Great Danes your whole life and have lost a few to bloat. There’s something to be said for doing whatever you can to avoid that traumatic, heart-breaking experience again. The most obvious time to consider it would be if you have an at-risk breed with a history of bloat in the line. Some might opt for prophylactic gastropexy on these breeds even with no history in the line.

If you do elect to have a prophylactic gastropexy performed on your dog, I encourage you to find a facility that offers it as a laparoscopic procedure. With laparoscopy, the incisions are much smaller, post-operative discomfort is way less, and recovery time is shorter than with traditional surgery, where the abdomen is opened with a large incision.

TREATMENT FOR BLOAT

Your dog will be given antibiotics, medication for pain, and started on intravenous fluid support to combat shock. Abdominal x-rays will be taken to see if the stomach has twisted. Decompression of the stomach as quickly as possible is of the utmost importance. This is achieved either by passing a tube down the esophagus into the stomach to let the gas out, or by passing a large needle through the dog’s side into the stomach to release the gas.

Once the stomach has been decompressed and cardiovascular status is stabilized, the dog is taken to surgery. At surgery, the stomach, if twisted, is repositioned and then sutured or tacked to the body wall (gastropexy) to prevent reoccurrence of GDV. Even if the stomach didn’t twist this time, gastropexy is recommended, as the risk of recurrence of bloat with twisting in the future is high. Any devitalized or necrotic stomach tissue identified is removed. The spleen is sometimes collaterally damaged when the stomach rotates and must be removed or partially removed if damaged.

Post-operative care is intensive. Even if your dog makes it through surgery, he is not out of the woods for at least the next 24 to 72 hours, as post-operative complications are common. These include infection, sepsis, DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation – a life-threatening diffuse clotting problem that can happen after a massive physiologic insult like this), and potentially fatal cardiac ventricular arrhythmias.

PREVENTION OF BLOAT

It’s pretty obvious this is a situation you’d be better off preventing if possible. The list of simple things to do to avoid bloat includes:

- Make sure there is no history of bloat in your potential puppy’s line.

- Avoid using elevated feeding bowls. These were once thought to help prevent bloat, but studies showed they actually increased its incidence.

- Add canned food to dry kibble meals; this has been shown to lessen risk of bloat.

- Feed at least twice a day, so meals are smaller.

- No exercise associated with meals. Do not feed after exercise until breathing is normal and relaxed. Promote rest for several hours after a meal.

- Consider a prophylactic gastropexy, especially for higher-risk dogs (see sidebar, above).

Even if prevention is not possible, the most important thing is to be aware of the signs of bloat and be ready to respond quickly.

The Problem With, “May I Pet Your Dog?”

It used to be that if folks wanted to pet your dog, they just reached out and did it. Happily, in today’s more well-informed world, there’s usually a quick, “May I pet your dog?” first. All too often, though, the moment that permission is granted, the stranger is moving in close and looming over the dog, swiftly thrusting a hand an inch from the dog’s nose. The dog – perhaps pushed forward a bit by the owner who sees how eagerly the other human wants this – might find an enthusiastic, two-handed ear jostle is next.

For some dogs – the stereo-typical Golden Retriever, perhaps? – this is the moment they’ve been waiting for! That extra human attention may even be the highlight of their walk. If your family has only included extroverted canine ambassadors like this, the idea that a dog would not welcome an outstretched hand is incomprehensible.

Yet, comprehend we must. Because, believe it or not, few dogs automatically love being trapped on a leash and touched by new people. As hard as it is for us to accept, that quiet dog being petted may well be hating every moment that the human is enjoying so much. While that’s important to understand when you’re the stranger in the scenario, it’s absolutely critical when you’re the one holding the leash.

DON’T ASSUME THAT DOGS WANT TO BE PETTED

Indeed, plenty of wonderful dogs are not eager to say hello to strangers. They may feel anything from uninterested, to wary, to terrified. In some cases, they have been specially bred – by humans – to feel what they’re feeling.

Unfortunately, because we humans value petting dogs so much, we often ignore that pesky truth. We tend to believe that all good dogs should happily accept petting from anybody at any time. But dogs have plenty of reasons for choosing to say no:

- Perhaps they’ve been bred to guard, so this forced interaction with strangers is deeply conflicting.

- Perhaps they’re simply more introverted and don’t enjoy this kind of socialization.

- Perhaps something in their background has made them less trusting of people.

- Perhaps normally they’d be all in, but today their ear hurts, or they are very distracted by the big German Shepherd staring at them from across the street.

There are many reasons, all legitimate, that may make a dog prefer to skip this unnecessary interaction.

DON’T GIVE CONSENT ON BEHALF OF YOUR DOG

Becoming conscious of just how deeply some dogs do not want to be randomly touched is the first step toward realizing that we really should be asking dogs, not their handlers, whether or not we can pet them. Ultimately, it’s the dog’s consent we need in order to safely pet them, not the human’s.

Maybe the idea of giving our dogs the right to consent feels strange to you. For my part, it feels downright creepy to not give my dog the right to consent or decline to being touched by a stranger. It feels wrong that I have the power to decree, “Sure, absolutely, you go right ahead and put your hands all over this dog’s body. She’s so pretty, isn’t she? We all love to touch her.” Ew!

Of course, dogs can’t verbally answer the “May I pet you?” question (when given the opportunity to do so), but they sure do answer with their body language. Unfortunately, most people don’t have the skills to read what can be very subtle signals, and as a result, many dogs are routinely subjected to handling that makes them uncomfortable. Worse, this often happens while they’re restrained by a leash with their owner allowing it.

That experience can make dogs even less enamored of strangers, and – the saddest part – less trusting of their owners, who did not step up to help them through that moment.

TIPS FOR MAKING FRIENDS WITH A DOG

I give my dogs agency when it comes to who touches them and when. If somebody asks, “May I pet your dog?” I smile at their interest and tell them I’d love for them to ask the dog. Then I show them how:

- Keep a little distance at first.

- Turn a bit to the side, so you don’t appear confrontational.

- Use your warm, friendly voice to continually reassure.

- Crouch down, so that you’re not looming in a scary way.

- Keep your glances soft and light instead of giving a steady stare.

- Offer your hand to sniff. But instead of the fist shoved unavoidably in the dog’s face (which is what society has been taught is the polite thing to do), simply move that hand ever so slightly toward the dog so she has a choice of whether to get closer to investigate. Look elsewhere as she does so, so she can have a little privacy as she sniffs.

Often, this approach gets us to a waggy “yes” from even a shy dog in 30 seconds!

HOW TO TELL IF YOUR DOG IS GIVING CONSENT

If the dog pulls toward the stranger with a loose, relaxed, or wiggly body, the dog is saying yes. Great! The next step is to begin petting the dog in the spot she’s offering – likely her chest or rump. (A top-of-the-head pat is on many dogs’ list of “Top 10 Things I Hate About Humans.”)

If my dog does not give a quick or easy “yes,” I may try backing us up a bit and making conversation, because many dogs warm up after having a few minutes at a safe distance to size up a new human. I might feed my dog a few treats while talking to the stranger, or give him some treats to toss near my dog. If she then relaxes and leans into the experience, great!

If not, we just call it a day and move along. That is also – and this is critically important – great! No harm, no foul. No need to apologize if our dogs say, “No thanks.” We can simply and cheerily head on our way.

A Healthy House for Your Dog (and You, Too!)

Maintaining a healthy home is in everyone’s best interests. Here are simple steps that can lead to a healthier home environment for you, your dogs, and your family.

NONTOXIC, PET SAFE CLEANERS

In recent years nontoxic household cleaners have become popular in supermarkets, natural food stores, and from online retailers. Some contain traditional ingredients like vinegar and baking soda, both of which you can use individually.

The acetic acid in distilled white vinegar kills harmful bacteria and microbes, plus it has antifungal properties that help resist mold. For a simple all-purpose cleaner, mix equal parts water and vinegar. Apply with a sponge, cloth, or spray bottle, then rinse or wipe with a clean, damp cloth and let dry. Make a spray that can help prevent ant or mite infestations around food storage areas by blending 1 cup distilled vinegar, 1 cup water, and a few drops of peppermint essential oil.

A popular do-it-yourself cleaner for vinyl floors combines 1 cup vinegar, 5 drops baby oil or jojoba oil, and 1 gallon warm water. The result removes waxy buildup and leaves the floor shining.

While recommended for kitchen counters, floors, sinks, mirrors, bathrooms, and windows, vinegar’s acidity can damage stone and should not be applied to granite countertops.

Baking soda, which is alkaline rather than acidic, is an effective scrubbing agent for sinks, countertops, and cookware, plus it’s a natural deodorizer. To remove odors, sprinkle baking soda on carpets before vacuuming and add to laundry wash water.

DUST AND VACUUM

Dust is often a challenge in homes with dogs. If yours is a shedder, you’ll want a good vacuum cleaner, Swiffer floor sweeper, lint rollers, or all three. Vacuum cleaners designed for use around pets feature allergen-capturing filters and attachments that work on floors, furniture, dog beds, and more.

To deal with flea infestations, vacuum areas frequented by your pets every two to three days, especially highly trafficked hallways and paths in your house. Flea eggs, larvae, and pupae can be found wherever a dog lives, and female fleas lay 20 to 50 eggs per day for up to three months. No wonder they’re hard to eliminate!

Flea larvae mature on or near the dog’s bedding and resting areas, so removing opportunities for eggs to develop is the most effective nontoxic flea population control strategy. Don’t forget to vacuum under cushions on couches or chairs that your dog sleeps on. Change vacuum bags frequently and seal their contents safely in a plastic bag (or empty bagless canisters into a plastic bag) before disposing.

HOW TO WASH DOG BEDS

Washing your dog’s bed is a good idea wherever fleas are a problem or whenever it needs a good cleaning, so check bed labels for cleaning instructions. Dog beds, blankets, throw rugs, and removable bed covers can be tossed in the washer with any detergent – you won’t need insecticidal soap, special detergents, or bleach because fleas cannot survive plain water. If desired, add baking soda as a deodorizer.

If a bed cover isn’t removable or the bed shouldn’t be washed, vacuum or clean it thoroughly, scrub it with a damp microfiber cloth, and wash the floor under the bed as often as possible. Purchase several covers, sheets, or towels for pet bed use and rotate them in and out of the wash.

HOW TO CLEAN FOOD AND WATER BOWLS

The best food and water bowls are made of stainless steel. Avoid ceramic bowls, as some decorative ceramics allow chemicals to leach into food and water. Plastic bowls may contain carcinogenic substances and can harbor bacteria.

Washing your dog’s food and water bowls with soap and hot water is especially important if you feed your dog raw meat because pathogenic bacteria can reproduce quickly at room temperature. Your dog should have access to fresh, pure water at all times.

NON-SLIP SURFACES

Slick or slippery floors, whether polished wood, vinyl, laminate, or tile, can pose health risks to dogs who have arthritis or are recovering from an illness or accident. Replace slippery flooring with bamboo or cork, both of which are slip-resistant, or use non-skid rugs, sisal grass runners, peel-and-stick carpet squares, yoga mats, or other skid-free surfaces wherever your dog needs traction.

You can discover a flooring’s slip-resistance by checking for its coefficient of friction, or COF, which is an objective standard of rating how slippery an item is. Manufacturers and retailers publish flooring COF ratings for comparison. Terracotta tile, quarry tile, and brick have high COF ratings, so they are very slip-resistant, while honed natural stone, which is slippery like glass, has one of the lowest COF ratings.

BRING THE OUTDOORS IN

Science tells us that dogs improve human health by bringing the outdoors in, but we don’t want a house full of muddy paw prints. Create an entrance plan to help keep things tidy. A mud room or garage entry, coupled with a super absorbent doormat or rug directly inside or outside the door will reduce incoming dirt. Have a good supply of towels, paw or body wipes, brushes, and grooming supplies nearby to simplify cleanup.

IMPROVE OR PRESERVE AIR QUALITY

You already know that, for your own health, you shouldn’t smoke. But did you know that second-hand smoke has been associated with lung and nasal cancers in smokers’ dogs? If you must smoke, do it outdoors and away from your dog. Don’t smoke in any enclosed space such as a closed room (or worse, in a car) with your dog present.

The air in the average home can be two to 20 times more polluted than the air outside. In addition to using natural cleaning products, open the windows in your home at least once a day unless the outdoor air quality is poor, such as when smog, air pollution, smoke from forest fires, or high pollen counts reduce air quality.

Whole-house and portable air filters remove dust, pollen, mold, and bacteria. Non-toxic houseplants improve air quality by removing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. Instead of using chemical “air fresheners,” use scented flowers, dried herbs, or aromatherapy essential oil diffusers to add fragrance.

KEEP YOUR YARD “GREEN”

Pet waste smells bad and can attract flies and spread worms. Removing it daily helps prevent health problems including coprophagia (when dogs eat their own or other dogs’ poop).

In place of commercial pesticides and herbicides, look for safe, organic compounds that can help control garden pests and keep your yard healthy without the use of toxic chemicals.

Every improvement you can make in the health of your home and yard will help your dog avoid common problems.

Dog Food, Protein, and Sustainability

What if we could give millions of pets a healthier, happier life and, in the process, make our planet healthier, too?” That’s the question that a pet food company called Jiminy’s was founded to answer back in 2016. Jiminy’s hoped to meet this lofty goal by replacing conventional sources of animal protein (such as chicken and beef) in its dog food with protein obtained from commercially grown crickets.

Yes, crickets. According to the calculator provided on Jiminy’s website, replacing a 50-pound dog’s beef-based food for one year with a cricket-based food containing the same amount of protein would save almost 3 million gallons of water, reduce the production of greenhouse gases equivalent to driving an average car more than 4,000 miles, and use 23 acres less land.

THE COSTS OF PROTEIN PRODUCTION

Protein is, of course, a critical component in dog diets. Animal-sourced proteins are the most commonly used proteins in pet food. In 2021, a report commissioned by the American Feed Industry Association’s Institute for Feed Education and Research, the Pet Food Institute, and the North American Renderers Association estimated that U.S. pet food manufacturers purchase 6.9 billion pounds of animal protein per year (report quoted by Pet Food Processing magazine).

According to a study published in 2017 by a researcher at the University of California – Los Angeles, dogs and cats are responsible for 25% to 30% of the environmental impact of meat consumption in the U.S. American pets consume more meat than humans in most countries worldwide.

The production of all those food-animal proteins has an enormous impact on the planet. Beef production is the largest driver of deforestation in South America. Producing a kilogram of beef causes the emission of almost 100 kilograms of greenhouse gas; by comparison, the production of one kilogram of peas results in a little less than one kilogram of greenhouse gas emissions. The production of both food animals and the food that must be produced to feed the food animals requires massive amounts of water; it’s estimated that 70% of all the freshwater withdrawals on the planet go to agriculture.

INDUSTRY RESPONSE

Jiminy’s may have gone further than any other company to directly address the environmental impact of pet food production, but it isn’t the only company making these calculations; the entire pet food industry has sustainability on its mind.

With an ever-growing global human population, there is ever-increasing competition for ingredients that can sustain humans and their pets alike. That causes the cost of the nutrients that dogs require to continually increase – and the cost of dog food to rise accordingly.

Pet food makers have a number of different tactics for meeting their consumers’ needs for protein. Each of these protein sources offer benefits and pose concerns for both the canine consumers they are made for and the planet. Most use a combination of the following:

- Human-edible animal-source proteins

- Meats and meat by-products that are not human-edible

- Plant-sourced proteins

- Insect-sourced protein

Historically, we’ve advocated for what we believe is nutritionally healthiest for dogs – the use of the highest-quality animal-protein sources that dog owners can afford – to the exclusion of all other factors (and that will continue to be the primary selection factor in our dog food reviews). After all, the amino-acid profiles of animal-sourced proteins more perfectly meet dogs’ nutritional requirements than plant-sourced proteins.

But perhaps we should all consider, at least once, the deleterious effect on the environment of producing all of that food – just for our pets. If the most dire predictions about climate change come to pass, dogs in the future will be fed very differently than they are now.

We know more than a few vegans and vegetarians who own dogs. Some feed their dogs vegan or vegetarian diets, not wanting to support the production and death of any food-source animals, even for their own dogs’ benefit.

Others feed their dogs conventional foods that contain animal-sourced proteins. A subset of these friends buy only those dog foods that offer third-party certifications that the meat sources used in the foods were humanely raised and/or wild-caught.

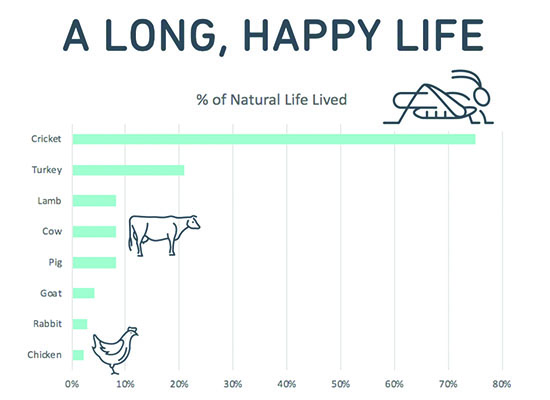

We’re not vegetarians nor vegans, but we’ve always admired the concept of “humanely raised” meats, and have sought to support companies that offer products with humane certifications. But we’d never before seen the particular animal-welfare consideration illustrated in this graphic, which we found on the Jiminy’s website:

Jiminy’s calls their food and treats “humane” partly because the insects used as the primary protein source in their products are able to live for a far greater percentage of what would otherwise be their natural life than any other food-species animals.

Jiminy’s also considers its products humane because of the way insects used in the food are raised and harvested. According to the company, “Crickets are naturally a swarming species and like being in a dark, warm place. They’re raised in cricket condos (inside barns) which allow the crickets to live in a way as close as possible to how they would live in the natural world. They are free to hop from feed station to feed station and can burrow deep into the condos if they choose. Harvesting time comes near the end of their natural life cycle – which is approximately 6 weeks. This comes after they have mated and laid their eggs. At the end, temperature is lowered and they go into a hibernation-like state before they’re harvested.”

HUMAN-EDIBLE MEATS AND MEAT BY-PRODUCTS

The phrase “edible” confuses everyone; isn’t all food edible? Well, no; not by the official definition of the word in this country. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the word “edible” means that it’s wholesome (untainted and fresh) and safe for humans to eat. People often use the phrase “human grade” to describe the same type of ingredient as “edible” but “human grade” has no legal definition.

“Meat” has a legal definition, and it refers to the muscle tissue of food-source animals.

There are a number of edible meat by-products (sometimes referred to as “offal”); these are non-muscle parts of slaughtered animals that are eaten but have been cut from a dressed carcass. These include foods such as liver, tongue, hearts, and pigs feet.

Human-edible animal-source proteins are among the most expensive ingredients that pet food makers have at their disposal. Since they have to pass the same inspections as for the foods we eat, they are as wholesome and nutritious as possible. They are kept clean and chilled throughout processing.

There are a very few products made for pets in human-food manufacturing facilities (see “Human Grade Dog Food,” WDJ December 2021”). There are probably more pet food makers that use human-edible meats in their products (mostly refrigerated and frozen diets), but unless the products are made with 100% human-edible ingredients in USDA-inspected human-food manufacturing plants, they cannot make “human-grade” claims on their labels or marketing materials.

Of all the protein sources available to pet food makers, meat and meat by-products have the greatest deleterious effect on the environment.

“NON-EDIBLE” MEATS AND MEAT BY-PRODUCTS

Non-edible meats include those that didn’t pass inspection for human consumption or have passed their sell-by date. Meat by-products include many nutritious parts of the animal that humans don’t typically eat, including organs, stomachs, intestines, bones, and poultry “frames” (what’s left of a bird after the feet, wings, neck, head, organs, and most of the meat have been removed). Blood, collected from freshly killed animals before they are butchered, is also considered a meat by-product.

Some meat by-products are used in canned, fresh/refrigerated, and frozen pet foods. Most meat by-products, however, are rendered – subjected to a process that separates the fat from the proteins, removes most of the moisture, and kills any pathogens present; the result is a low-moisture meal. According to the North American Renderers Association, without rendering, roughly 50% of each meat animal would go to waste.

We’ve recently become convinced of the value of a meat by-product that we were strongly opposed to in the past: spray-dried porcine and bovine plasma. Blood is collected in slaughterhouses that are specially equipped for its capture. The blood is chilled and transported in food-grade, species-dedicated tank trucks to processing plants where it is treated with ultraviolet photopurification, centrifuged (to remove red and white blood cells), concentrated, and dried.

Plasma contains albumin proteins with bioactive peptides and immunoglobulin G (IgG). Studies indicate that its inclusion in canine diets support immune and gut health. It’s been used as a thickener in canned foods for some time, often disguised under another of its legal names, “natural flavor.” Increasingly, it’s being added to dry dog foods as a palatant (reportedly, dogs love its taste) and protein booster.

Over the years, mankind has gotten increasingly inventive in finding uses for by-products of the meat industry. If these materials went unused, it would make the environmental impact of their production even more egregious than it is.

PLANT PROTEINS IN DOG FOOD

There are a number of protein-containing grains and legumes (and grain and legume by-products) used in dog food production. Some have been used for many decades; others are just emerging as potential replacements for animal-protein sources. The most commonly used plant proteins used in pet food include:

- Algae (aquatic plant)

- Beans

- Brewers dried yeast

- Chickpeas

- Corn

- Duckweed (aquatic plant)

- Fava beans

- Lentils

- Lupin beans

- Peas

- Potatoes

- Quinoa

- Rapeseed

- Rice

- Soybeans

- Sunflower seeds

- Wheat

The environmental impact of growing all of these plant sources of protein is far less than that of producing an equivalent amount of animal protein. However, more care must be taken to ensure the resulting products are formulated to fully meet the dog’s nutritional needs – the amino acids in particular.

Another drawback of foods that contain only plant-sourced proteins is that they tend to be far less are less palatable to dogs. According to Pet Food Industry, characteristic off-flavors from plant proteins in pet food include bitterness and astringency.

Finally, plant-derived protein sources also carry the risk of mycotoxins – toxins that are produced by fungi that can infect certain plants. The higher the inclusion of ingredients that can be contaminated with mycotoxins, the higher the risk of mycotoxin poisoning.

INSECT-SOURCED PROTEIN DOG FOOD

As previously mentioned, crickets are being used by Jiminy’s in treats and its “Cricket Crave” dog food. Cricket protein is reportedly more expensive than any animal protein, but as more entrepreneurs figure out cricket farming, and more commercial cricket farms come onto line, the price of this unique protein will descend.

Cricket protein production has an exponentially smaller carbon footprint and less water consumption than conventional animal protein production. Nutritionally, it has some other advantages: It’s highly digestible, exceeds the amino acid requirements set by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), and (due to its fiber content), functions as a prebiotic (a microbial food source that promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut).

Jiminy’s also uses another protein sourced from dried larvae of the black soldier fly. Nestlé has announced it’s launching a pet food that contains this protein, initially to be sold only in Switzerland, and there are several other foreign pet food manufacturers offering dog food containing insect meal. These foods are promising, but given their newness and dearth of feeding trials, we’d recommend using them only in rotation with more conventional diets.

On The Fence

I’ve been fostering a very special scruffy-faced pup for a little more than two months now. It pains me to say that, while I truly do love him to pieces, I am still on the fence about whether or not to keep him.

I’ve justified his extra-long stay here with a couple of different excuses. At first, it was because I wanted the chubby, wobbly puppy to lose a little weight and develop a little muscle; it seemed like he had trouble with his knees. I thought it would be best to be certain that his lack of strength and coordination was simply due to a lack of opportunity to exercise and not some serious abnormality that should be addressed or corrected before we tried to find him a home. I wouldn’t want him to get placed with someone who had neither the time nor resources to fix whatever problem he might have.

He was so much bigger and thicker than the litter of 11 unrelated pups I was also fostering, and didn’t appear to be any particular breed or type, so I went ahead and ordered a mixed-breed DNA test for him. I told my husband that since we had no clue about his breed, we’d have a hard time telling prospective adopters how big he might become. I told my friends that I was waiting for the results before promoting him for adoption, so I could better represent him as something or other, to make sure he ended up in a home that was appropriate for his size.

The litter of 11 all went back to the shelter and got adopted, he slimmed down and muscled up, and his legs started looking fine. The DNA tests results came back and indicated he’s going to be a medium-large dog. According to Wisdom Panel, he’s (in descending order) American Staffordshire Terrier, American Pit Bull Terrier, Boxer, German Wirehaired Pointer, American Bulldog, English Springer Spaniel, Great Dane, Australian Cattle Dog, German Shorthaired Pointer, Labrador, and In other words, medium-large.

Then, my husband and I were leaving for a week’s vacation, and I didn’t have time to show him to anyone before we left, so he stayed with my sister-in-law and niece while we were gone. (They fell in love with him, too.) When we got home, I was busy doing all the things that pile up while you’re away on vacation, which meant no time to schedule any meet-and-greets.

Though my stated reason to not keep the puppy has been to give Otto, my 14 1/2-year-old dog, a peaceful last year or so, the puppy hasn’t really been bothering Otto at all. Help! I’m running out of excuses!