There’s an old saying: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” Fortunately for our beloved dogs, that’s not necessarily the case in the world of dog training and behavior. Granted, there are still far too many professionals who cling to old-fashioned methods that employ the use of force, pain, and coercion. For them, things do seem to stay the same. However, the corps of enlightened training professionals that routinely read about, absorb, and apply innovations of behavior science grows daily, and I’m proud to consider myself one of these.

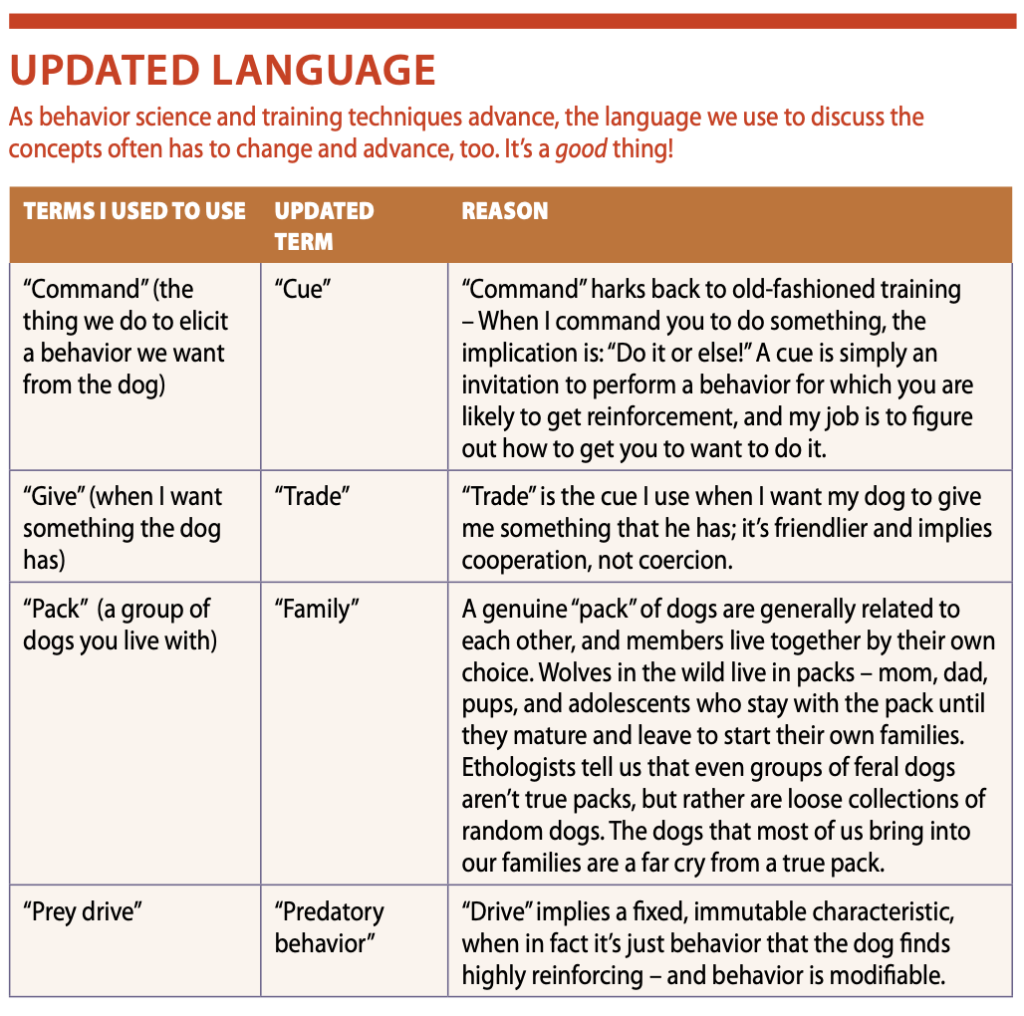

Of course, that means from time to time I have occasion to change what I say and how I say it. I sometimes look back at something I wrote years ago and cringe when I realize that, as much as there may have been general agreement with it in the profession then (whatever it is), there is growing or widespread agreement now that it isn’t really so. Here are some examples of things about which I have changed my mind over the years:

* The importance of putting reinforcers on an intermittent schedule of reinforcement.

Early on, when using treats in training was somewhat revolutionary, we “foodies” took a lot of heat for our use of treats. As a result, in the past, we put a lot of emphasis on moving the dog from a continuous schedule (in which he gets reinforced every time – very important when he is first learning a new behavior) to an intermittent schedule of reinforcement, which means he learns to offer the behavior multiple times when asked and gets reinforced only occasionally. Continuous reinforcement, we thought, would make dogs and humans dependent on the presence of the treat in order to get the behavior to happen.

We have come to realize that it’s not all that important to use intermittent reinforcement unless you need the behavior to be durable – resistant to extinction. There is absolutely nothing wrong with reinforcing the behavior every time it happens. And I pretty much do! The Miller dogs are generally on a continuous schedule of reinforcement, even if it’s sometimes just a cheerful “Good dog!”

Remember, “reinforcement” doesn’t have to mean a treat. While I almost always have treats in my pockets, I can also use praise, a toy, petting (for dogs who love to be petted), opening a door to go outside, the opportunity to perform another behavior the dog loves – or anything else the dog finds reinforcing, in place of a treat.

We do know that a behavior extinguishes over time if it is not reinforced and that behaviors that are intermittently reinforced are more durable than others. But how many of us are often in environments with our dogs where we can’t reinforce behavior every time, or most of the time? I can think of a few – a dog in an American Kennel Club obedience trial, a canine actor on stage in a play, a working dog who, by nature of his job, has to work at a distance from his handler . . . not all that many!

In the real world, few owners “over-reward” and end up with dogs who refuse to work unless a treat is shown to them first. More commonly, I see owners who fail at “catching their dogs doing something right” – that is, fail to frequently reinforce their dogs for the behaviors they like to see. Lacking reinforcement, and thus, experience that teaches them which behaviors will reliably result in enjoyable consequences produced by their owners, dogs will find things to do that please themselves!

That’s why I now advise you to reinforce your dogs any and every time you see behaviors you like – looking at squirrels out the window without barking, going to her mat when the family sits down to dinner, checking in with you on a walk, greeting friends at the door with all four paws on the floor. And reinforce these terrific behaviors with anything your dog finds enjoyable – a treat, a cheerful word, a belly rub, a favorite toy, or a rousing game of tug o’ war.

* Rules for playing tug o’ war with your dog.

Speaking of tug, I’ve considerably lightened up on my recommended “rules for tug o’ war” with dogs. Again, sensitive to criticism from the old-fashioned trainer crowd, we used to dictate strict rules for playing tug with your dog. Playing tug even under these rules used to be considered dangerous by many old-school trainers, who warned owners that tug could make their dogs aggressive. I wouldn’t ever go that far – though I certainly wouldn’t advise an inexperienced owner to casually play tug with an already aggressive dog or one who is known to guard resources.

Many dogs love to play tug with their owners, so it has a ton of potential for use as a mutually enjoyable and fantastically reinforcing game. To get the most out of the reinforcing nature of the game, ask your dog to play by some basic rules; to keep yourself safe, play with a few safety guidelines in place. Here are my current rules and guidelines for playing tug:

• Use a toy that’s long enough to keep your dog’s teeth far away from your hands and that’s comfortable for you to hold when he pulls.

• Hold up the tug toy. If your dog lunges for it, say “Oops!” and quickly hide it behind your back. He needs to be polite when he plays tug with you.

• When he’ll remain sitting as you offer the toy, tell him to “Take it!” and encourage him to grab and pull. If he’s reluctant, play gently until he learns the game. If he’s enthusiastic, go for it!

• Randomly throughout tug-play, ask him to “Trade!” Offer him a yummy treat, which he can take after he relinquishes the tug toy to you. Then, offer the toy and tell him to “Take it!” again.

• While you are playing, if his teeth creep up the toy toward your hands, say “Oops! Too bad!” in a cheerful voice, have him give you the toy, and put it away briefly. (This is for safety reasons. You can get it out and play again after 15 seconds or so.)

• If your dog’s teeth touch your clothing or skin, say “Oops! Too bad!” and put the toy away for a minute (again, for safety reasons).

• Children should not play tug with your dog unless and until you are confident they can play by the rules. If you do allow children to play tug with your dog, always directly supervise the game.

• Only tug side to side, not up and down (up and down tugging can injure your dog’s spine) and temper the vigor of your play appropriately to the size and age of your dog. (You can play tug more vigorously with an adult Rottweiler than you can with a Rottie puppy or a little terrier.)

Here are the rules for tug that I have discarded or modified:

• Keep the tug toy put away. Bring it out only when you want to play tug. (There is no logical justification for keeping the tug toy away from the dog at other times.)

• Ignore the dog if he invites you to play tug. You get to decide when tug happens. (What does it hurt if your dog asks you to play? You can always say, “No thanks! Not now!”)

• You should “win” most of the time – that is, you end up with possession of the toy, not your dog. (As long as you allowed the dog to take the toy, and he didn’t take it in an aggressive manner, there is no harm in letting him have it sometimes, or even frequently. In fact, some dogs quickly learn that playing with the toy by themselves is nowhere near as much fun as playing with you.)

• When you are done playing, put the toy away until next time. You control the good stuff. (Playing with you is the really good stuff! It’s fine to let the dog trot off with the toy when you’re done, as long as it’s safe for him to have.)

As you can see, I’ve removed all the rules that insist you always have to be in total control of the game – the ones that were based in the old-fashioned thinking that if you weren’t in total control your dog would take advantage of you and perhaps even become aggressive. We know better now. Happy tugging!

* Leave It/Walk Away

Many of us teach our dogs a cue to “Leave it!” (also known as “Off!”) for use in those situations when you see something you don’t want your dog to mess with – whether it’s a pile of cat poo, a discarded chicken bone, a cat crossing the sidewalk, or a snake. I still teach that cue for use when I want the dog to understand “Whatever you are coveting or considering going toward, I want you to leave it alone.” But I also teach an alternative cue, “Walk away,” which means “Whatever you are looking at, I want you to do a 180-degree spin and run away with me.”

While there are many situations where the two cues could be used interchangeably, and some cases where “Leave it” is still the more appropriate choice, I find that dogs respond much more reliably to the “Walk away” cue, simply because we teach them that it’s a fun game. Given the choice, it’s my much-preferred behavior to ask for.

I first discovered this with my Cardigan Corgi, Lucy. She had learned “Leave it!” in her adolescence and responded reasonably reliable to that cue. When she was 10 years old, I learned about New Jersey trainer Kelly Fahey’s “Walk away” protocol, and taught it to Lucy.

Then I did an experiment. I set a bowl of tasty food on the floor, and as Lucy walked toward it, I said, “Leave it!” She took two more steps and started eating. Then I said, “Walk away!” and she spun away from the bowl and ran away from it with me.

The moral of the story and a good reminder: We are almost always more successful asking our dogs to do something (run away with me!) than not to do something (don’t eat that!). It’s one of the basic tenets of positive reinforcement-based dog training.

For complete instructions on teaching “Walk away” to your dog, see the “Walk Away!” sidebar in the “Frustrated on Leash?” article in the October 2019 issue of WDJ.

* Head halters can help – or hurt.

Just like almost every other positive trainer, I was enthusiastic about head halters when they first made the training scene around 1995. They helped many people prevent their dogs from dragging them around on walks, without the use of painful yanks from choke chains or pinching prong collars. With a regular collar, the leash is attached at the dog’s neck; with a head halter, the leash attachment is right under the dog’s head, making it very difficult for him to brace against the leash and pull. Gentle pressure on the leash from the handler turns the dog back toward the handler.

But the more we saw halters used, the more it became clear that the majority of dogs hated them, even after fairly thorough efforts were made to desensitize and counter-condition dogs to wearing them.

Then front-clip harnesses came along and fulfilled much of the same function: giving us a significant degree of control over dogs who pulled hard. It was easy to switch my allegiance to these new products (and we described all the reasons for this in the February 2005 issue of WDJ).

Most dogs accept harnesses without protest, and they are far less likely to do damage to a dog’s neck or spine if they hit the end of the leash hard. (I occasionally come across a dog who finds front-clip harnesses aversive, and I don’t use them with those dogs.)

For a review of front clip harnesses, see “Harness the Power,” WDJ April 2017.

* Modified recommendations for crating your dog.

Some people believe that confining your dog in a crate – ever – is cruel. Never fear: I am still a strong advocate for crating. There are a couple of things regarding crates, however, that I do differently now than I did years ago.

I used to be on board with this common caveat to owners: “If your dog/puppy is crying in his crate, ignore him until he stops crying, or you will reinforce his vocalizations.” I shudder now to think of that.

Okay, granted, if your dog barks a few times, it’s still good advice to ignore it so you don’t reinforce him for barking. But anything beyond that – ongoing, emotional vocalization – needs to be addressed behaviorally. Leaving a dog to cry in his crate for long periods increases his stress and gives him an even more negative association with being crated.

A dog who is stressed about crating but still needs confinement for management purposes needs a gradual program of habituation (a few seconds at first with you right there, then longer and longer, with you gradually removing yourself), or needs alternatives to crating (an exercise pen or a dog-proofed room).

My other change having to do with crates regards size. I used to say that a dog’s crate should be just big enough for him to stand up, lie down, and turn around. That is still true if you’re housetraining – you don’t want the crate to be big enough that he can soil one end and sleep dry and comfortably in the other.

But after he is housetrained, if he still needs to be crated, there’s no reason to continue to deprive him of more spacious quarters.

THE GOOD NEWS

In general, the positive dog training world has made a quantum shift from, “I will make the dog do want I want him to do … I bought him so I could compete with him in agility and he’s damn well going to do it!” to “I will explore options with my dog to see what he would like to do. I’ll be really happy if he wants to do agility, since I love agility, but if he tells/shows me that he would prefer to do nosework, or rally obedience, or canine freestyle, I’m good with that, too.”

Personally, I have also made a quantum philosophical shift. I used to be fiercely competitive with my dogs. My wonderful terrier-mix (and “crossover dog”) Josie had multiple obedience titles and was one of the first 26 dogs in the world to earn a rally obedience title through the Association of Professional Dog Trainers (APDT). I no longer need my dogs to be precise competitors, doing perfectly straight sits in perfect heel position; just being who they are is good enough. Today, while I respect those who find joy in mutual partnership and competition with their dogs, I just want to be with mine, doing barn chores, hiking on the farm, and sharing and enjoying our life together.

As I read through my past writings to find things that I now disagree with, I was pleased to find there weren’t as many as I thought there might be. I went through my articles all the way back to Whole Dog Journal’s inception in 1998, and didn’t find anything horrendously objectionable. Yes, I found some things I would do or say differently now, but nothing that would get me kicked out of the force-free trainer club. It’s always good, though, to remind ourselves that when we know better, we do better.

Author Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT‑KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She and her husband live in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center, where she offers dog-training classes and courses for trainers. Miller is also the author of many books on dog-friendly training. See page 24 for more information.

Thank you so much for sharing the information in this post! I think it’s now to delete all the pain, coercion, shouting,…in dog training!

My kids love karate we do karate 4 o 5 times a week that’s a great sports i recommend!!

In my opinion, this is a very useful article. I think it is very important to train a dog from an early age. My first dog was trained by a professional dog trainer. I trained my second dog myself and I realized that it was very difficult. True, you do not need to treat the dog very often with delicious things, because it will get used to and train the dog will be even harder. Before training a dog, you need to read many professional books.