When it’s time to buy food for your dog, how do you choose? Do you just look for something you’ve heard of before? Go with whatever they were feeding at the shelter or breeder? Shop by price? Ask your veterinarian?

Any of those selection methods might result in a good choice—or you could end up with a wildly inappropriate diet for your dog. Choosing a dog food is not a one-size-fits-all proposition! No food is “best” for all dogs; there’s not even a single pet food company whose products are ideal for all dogs!

Here’s how we choose foods—and our top picks for different types of dogs or situations. We hope that your search can be facilitated by the process we used to select our top recommended dry dog foods (and nearly 20 runners up) in eight different categories.

Start With Our Approved Dry Dog Foods List

You’re likely aware that there are hundreds of dog food companies and thousands of foods to choose from—and the vast majority are not, in our opinion, all that great. To winnow down the contenders, we’ve created a list of companies that make the kind of foods we like: “WDJ’s Approved Dry Dog Foods”. When we go shopping, we consider only foods from companies on that list.

Next, we look at the individual products made by these companies. We’ve made a spreadsheet for each product they offer and entered every bit of information about them: their complete list of ingredients, amount of protein and fat they contain, whether they are formulated for adult maintenance or can be fed to growing puppies—and if so, whether or not they can be fed to large-breed puppies, who shouldn’t consume high levels of calcium and phosphorus.

By using the spreadsheet, we can scan, sort, and compare ingredient lists. We start our search for any type of dog food by analyzing the candidates’ ingredients, looking for attributes of quality—as well as traits that tend to indicate low-quality foods.

Finally, to select the best candidates for foods for specific dogs, dogs whose needs are typical of a certain type (such as highly active dogs, fat dogs, large-breed puppies, etc.), or dogs who belong to humans with budgetary limitations or ethical qualms about buying a meat-based diet, we use more refined criteria. We’ll describe those criteria within each category of foods.

SUBSCRIBER ONLY: The Complete List of Whole Dog Journal’s 2025 Approved Dry Dog Foods

All Life Stages Dry Dog Food/Puppy Food

By law, every dog food label bears a tiny statement that tells consumers whether the product is “complete and balanced” (contains all the nutrients a dog needs in appropriate amounts). This is known as the nutritional adequacy statement or the AAFCO statement, as it references the Association of American Feed Control Officials, who developed a set of nutritional standards for puppies and pregnant or nursing females (called “growth and reproduction”), and a separate set for adult dogs (“adult maintenance”).

If the food has been formulated to meet the needs of dogs in a growth or reproduction phase, the AAFCO statement may reference “growth,” “growth and reproduction,” or “dogs of all life stages.” Growing, pregnant, and nursing dogs need more protein, fat, calcium, phosphorus, and several other minerals than adult dogs—but it’s fine for adult dogs to consume foods with these higher nutrient levels; thus the “all life stages” label.

Whether we’re looking for a food for a growing puppy or a reasonably active adult dog, we look among prospects that have moderate levels of protein. The minimum percentage of protein for growth is 20% “as fed” (how it’s listed on product labels). There is no maximum dictated by the AAFCO dog food nutrient profiles, but few foods exceed 40% protein as fed, so we’d consider 30% protein (as fed) to be moderate; we look for foods with protein levels around that number.

If the food contains supplements such as probiotics, taurine, or glycosaminoglycans (i.e., glucosamine, chondroitin), we want to see them listed on the guaranteed analysis, indicating they are present in verifiably beneficial quantities, not just token window dressing.

Whether we are shopping for a food for a puppy or adult dog, our preference is always for a product with meat and/or a meat meal in the top two ingredients; more meats in the top five or so spots on the ingredients list are even better. We also prefer legumes (such as peas, chickpeas, and lentils) to be used only in minor roles (below the 5th or 6th position on the ingredients list).

Dry Dog Foods for “Adult Maintenance”

Adult maintenance foods often contain lower levels of protein and fat than foods that are formulated to meet the needs of puppies and nursing or pregnant mothers. But, again, AAFCO has not issued maximum levels of fat or protein for any life stages, and some foods formulated for adult maintenance may contain more fat and protein than some foods for all life stages. So, when shopping for an adult maintenance food, take a peek at the protein and fat levels in any food you consider to make sure the amounts are appropriate for your dog. Less-active or overweight adult dogs don’t need foods with super high levels of protein or fat.

If you are unsure about what level of fat is appropriate for your dog, compare the caloric content of the foods you are considering. Fat contains more than twice the calories (9 per gram) of protein and carbohydrates, which each contain 4 calories per gram.

Low Fat Dry Dog Foods

The legal minimum amount of crude fat in a dry adult maintenance food is 4.95% (“as fed,” a term that means this percentage is expressed for the form of food that is in the package); for puppies, the minimum is 7.65% (as fed). In this category, we selected foods with fairly low (but not the lowest) amounts of fat for adult dogs; none of our selections would be appropriate, however, for growing puppies. The dogs who are most in need of low-fat foods are those who are inactive and sedentary, have diabetes, are overweight, have pancreatitis, or are of a breed that is genetically predisposed to pancreatitis.

Remember that dry dog foods contain protein, fat, and carbohydrates; you can’t make a kibble without carbs! When you reduce the amount of any one of those three macronutrients, one or both of the other two will rise—so some lower-fat foods will contain increased levels of protein, some will contain increased levels of carbohydrates, and some will contain increased levels of both. This is where, as always, you need to take your own dog’s unique needs into account. Does he do better on higher-protein or higher-carb foods?

Our top picks in low-fat foods reflect products that take a balanced tack, with increased amounts of protein and carbs. We didn’t select the foods with the very lowest amounts of fat that are on our Approved Dry Dog Foods list. If your dog has suffered one or more episodes of pancreatitis, you may wish to look among those products with the very lowest possible fat levels.

High Protein Dry Dog Food

To repeat, there are no established maximum values for protein in dog food. Dogs can eat and thrive on food that contains twice (or even more) than the minimum amounts of protein they require. This amount of protein is not necessary, however, and foods with high protein levels are much more expensive than lower-protein foods. That said, some dogs absolutely do better on high-protein foods than they do on foods with more moderate or lower protein levels. Particularly active dogs, fit senior dogs, and canine athletes—particularly dogs who are used in endurance or cold-weather activities—may do better on high protein foods.

We don’t generally select foods with the very highest levels of protein for our favorites; we chose foods that were among the highest 20% or so.

Limited Ingredient Dry Dog Food

There isn’t a commonly agreed-upon definition of limited-ingredient dog foods. Some manufacturers will use just five or six major ingredients (the sources of protein, fat, and carbs) in their limited-ingredient foods, while others will contain 10, 12, or more.

Usually, those of us who are considering a limited-ingredient diet are either feeding a dog who is sensitive to either known or as-yet unknown ingredients, trying to prevent aggravating a hypersensitive (allergic) response, or trying to identify which ingredients the dog can digest without triggering an adverse response. The more ingredients a food has, the harder it is to identify exactly which ingredient is troubling the dog—so our bias in selecting favorites in this category is for foods with as few major ingredients as possible.

Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

In our opinion, grain-free foods became far too popular (and for no particular reason!), which led pet food makers to search for every non-grain carbohydrate source they could find (because, again, you can’t make a kibble without carbs). Potatoes, sweet potatoes, and legumes (peas, lentils, chickpeas, and beans) were the most popular ingredients pressed into service to meet the demand for grain-free foods.

In 2018, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration started a firestorm of controversy by publishing a preliminary advisory warning of a possible link between grain-free foods and the incidence of canine dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Despite much study, that link has not been proven, though a link between higher rates of DCM and foods with high inclusions of legumes is still suspected. Today, we feel confident that there is no link between the broad category of “grain-free foods” and canine DCM, and that even foods with a high legume inclusion are safe for dogs as long as their maker adds adequate amounts of taurine and/or its metabolic precursors, methionine and cysteine.

Pet food makers like the higher inclusion of legumes because they can serve double duty as a carbohydrate source as well as a source of protein that is less expensive than animal protein. But the amino acid profile of animal proteins suit dogs better than plant-based proteins. So we feel most comfortable recommending grain-free foods only when they contain a relatively low inclusion of legumes, and for dogs who have a demonstrated lack of ability to thrive on foods that contain grain.

Budget Dry Dog Foods

Our “budget” foods are more expensive than the cheapest foods you can find, but that’s because the cheapest foods you can buy would be disqualified from our approved foods list by several criteria.

The least expensive foods usually use plant proteins (such as corn and peas) rather than animal proteins as their main protein sources. They often contain unnamed animal protein and fat sources (identified on the ingredients list only as “meat,” “meat meal,” or “meat and bone meal,” and “animal fat”)—or just “animal by-products or “poultry by-products.” And, finally, the least expensive foods usually contain highly processed grain by-products—waste from the human food industry. We just can’t recommend those foods.

Dry Dog Foods Containing Alternative Proteins

While they are quite rare, some dogs are hypersensitive (allergic) to all or most animal protein sources. Also, many people have ethical, moral, and/or environmental objections to raising and killing animals to feed their dogs. Fortunately for individuals of both kinds, there is an increasing number of complete diets for dogs that contain no “dead animal” sources of protein.

We’re aware of fewer than 10 foods that fit in this category. Some are vegetarian, some are vegan, and some are . . . well, we’re not quite sure what to call products that use insect sources of protein!

Note that all of these meat-free foods are formulated for adult maintenance only; none are appropriate for puppies.

Best Dry Dog Food by Category

SUBSCRIBER ONLY: The Complete List of Whole Dog Journal’s 2025 Approved Dry Dog Foods

Best All Life Stages Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Three meats in the first six ingredients

- Inclusion of marine micro-algae oil, a vegan source of EPA and DHA

- Many nutrients on the guaranteed analysis, including EPA and DHA (especially beneficial for puppies) and taurine

First 10 ingredients: Deboned chicken, chicken meal, brown rice, barley, oatmeal, turkey meal, dried plain beet pulp, chicken fat, flaxseed, pumpkin

Protein: Min 31%

Fat: Min 15.5%

Calories: 421 Kcal/cup

Cost: $3.15/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Chicken meal, Brown Rice, Oatmeal, Dried Beet Pulp, Chicken Fat (Preserved with Mixed Tocopherols), Dried Egg, Brewers Dried Yeast, Natural Chicken Flavor...

View all

Ingredients:

Organic turkey, Organic chicken meal, Organic oats, Organic brown rice, Organic flaxseed, Organic tapioca starch, Organic chicken fat (preserved with mixed tocopherols), Organic chicken liver...

View all

Ingredients:

Chicken, oats, barley, chicken liver, carrots, eggs, ground flaxseed, broccoli...

View all

Best Adult Maintenance Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Three meats in the first six ingredients

- Many extra nutrients on the guaranteed analysis, glucosamine, chondroitin, taurine, probiotics

- Baked food, not extruded

First 10 ingredients: Whitefish, whitefish meal, oatmeal, barley, sunflower oil, salmon, flaxseed, tomato pomace, cod, quinoa

Protein: Min 27%

Fat: 14%

Calories: 453 Kcal/cup

Cost: $2.77/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Chicken meal, Brown Rice, Chicken Fat (Preserved with Mixed Tocopherols), Whole Dry Eggs, Herring meal, Millet, Dried Beet Pulp, Brewers Dried Yeast...

View all

Ingredients:

Deboned Beef, Turkey meal, Chicken meal, Barley, Oats, Spelt, Chicken Fat (preserved with Mixed Tocopherols & Citric Acid), Ground Flaxseed...

View all

Ingredients:

Chicken, oats, barley, chicken liver, carrots, eggs, ground flaxseed, broccoli...

View all

Best Lower-Fat Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Maximum % of fat also listed on guaranteed analysis

- Though meat is not first on ingredients list, two fresh meats and two meat meals immediately follow brown rice (2nd–5th)

- Peas play a supportive role, but not too high on ingredients list (7th)

First 10 ingredients: Whole grain brown rice, chicken, turkey, chicken meal, turkey meal, cracked pearled barley, peas, oatmeal, white rice, faba beans

Protein: Min 21%

Fat: Min 6%, Max 9%

Calories: 328 Kcal/cup

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Chicken meal, brown rice, millet, sorghum, oat, barley, rice bran, dried beet pulp...

View all

Ingredients:

Pork meal, Dehulled Barley, Peas, Ground Brown Rice, Oatmeal, Rice, Tomato Pomace, Chicken meal...

View all

- Grandma Mae’s Low Fat Entrée (Min 7% fat)

Best High Protein Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

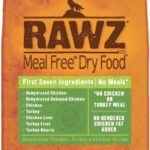

- Ingredients list starts with two dehydrated meats, then two meats, then three organ meats

- Despite high protein, moderate fat level (12%)

- Taurine added to formula

First 10 ingredients: Dehydrated chicken, dehydrated deboned chicken, chicken, turkey, chicken liver, turkey liver, turkey heart, pea starch, dried peas, tapioca starch

Protein: Min 40%

Fat: Min 12%

Calories: 462 Kcal/cup

Cost: $6.65/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Chicken, chicken giblets (liver, heart, gizzard), cod, whole herring, turkey giblets (liver, heart...

View all

- Wellness Core+Wholesome Grains Puppy (37% protein)

Best Limited Ingredient Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Novel protein from two species of fish (whitefish and herring) may benefit dogs with allergies to more common proteins

- Quinoa is also a novel carb source for many dogs

- First 10 ingredients: Whitefish, herring, whitefish meal, herring meal, quinoa, pumpkin, olive oil, dicalcium phosphate, natural whitefish flavor, calcium carbonate

Protein: Min 35%

Fat: Min 17%

Calories: 429 Kcal/cup

Cost: $4.54/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Turkey meal (Natural Source of Glucosamine and Chondroitin), Pumpkin, Butternut Squash, Tapioca, Sunflower Oil (Preserved with Mixed Tocopherols), Flaxseed, Dried Yeast, Natural Flavors...

View all

- Natural Balance Limited Ingredient Chicken & Brown Rice Recipe

Best Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Six meats and meat meals in the first six spots on the ingredients list

- Several legumes, but low on ingredient list (even combined, not present in an excessive amount)

- Added taurine

First 10 ingredients: Chicken meal, turkey meal, salmon meal, deboned chicken, deboned turkey, deboned trout, potatoes, peas, tapioca, lentils

Protein: Min 32%

Fat: Min 14%

Calories: 394 Kcal/cup

Cost: $3.68/lb

Runners up:

- Farmina N&D Brown Lamb, Norwegian Kelp, & Carrot Recipe

Ingredients:

Deboned Beef, Pork meal, Salmon meal, Oats, Barley, Tapioca, Pork, Pork Fat (preserved with Mixed Tocopherols)...

View all

Best Budget Dry Food

Things we like:

- Deboned meat (a lower-ash ingredient) and a meat meal 1st and 2nd on ingredients

- Many extra nutrients (including probiotics) on the guaranteed analysis

First 10 ingredients: Deboned chicken, chicken meal, ground brown rice, pearled barley, oat groats, rice bran, chicken fat, dried plain beet pulp, flaxseed meal, natural chicken flavor

Protein: Min 25%

Fat: Min 15%

Calories: 362 Kcal/cup

Cost: $2.33/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Chicken, turkey, chicken meal, turkey meal, cracked pearled barley, whole grain brown rice, peas, oatmeal...

View all

Ingredients:

Deboned Chicken, Chicken meal (source of Glucosamine and Chondroitin Sulfate), Oatmeal, Barley, Brown Rice, Peas, Dried Plain Beet Pulp, Chicken Fat...

View all

Best Alternative Proteins Dry Dog Food

Things we like:

- Eco-friendly, humane, sustainable formula

- Grub protein is highly digestible and prebiotic (helps feed beneficial bacteria in the gut)

- Baked, not extruded

First 10 ingredients: Dried black soldier fly larvae, oats, dried yeast, sweet potato, potato protein, sunflower oil, brown rice, dried plain beet pulp, dicalcium phosphate, natural vegetable flavor

Protein: Min 28%

Fat: Min 14%

Calories: 426 Kcal/cup

Cost: $4.12/lb

Runners up:

Ingredients:

Vegetable Broth, Potatoes, Ground Brown Rice, Ground Barley, Oats, Potato Protein, Carrots, Canola Oil (Preserved With Mixed Tocopherols)...

View all

- Open Farm Kind Earth Premium Insect Kibble Recipe (protein sources are black soldier fly larvae and dried yeast)