Coconut oil, an edible fat derived from the meat and milk of the coconut palm fruit, is often touted as a superfood for dogs. At temperatures above 75°F, coconut oil is a clear liquid; at colder temperatures, it’s solid and white, like vegetable shortening.

What Does Coconut Oil Do for Dogs?

The alleged benefit with the most evidence to support it is that supplementation with coconut oil may have a positive effect on dogs with epilepsy, by reducing the frequency and intensity of seizures. Recent studies, such as “Efficacy of medium chain triglyceride oil dietary supplementation in reducing seizure frequency in dogs with idiopathic epilepsy” (Veterinary Record, October 31, 2020), have so far been small in size, and their protocols differ, but most conclude by recommending further research on the use of coconut oil in the management of canine epilepsy. (See sidebar for more study references.)

Used topically, coconut oil has been credited with soothing dogs’ itchy skin and insect bites, combating ear mites, and healing mange, wounds, and ear infections. As an addition to dogs’ diets, it’s believed to help improve arthritis symptoms, dull coats, digestive problems, and unpleasant body odors. Unfortunately, none of these claims have been tested in clinical trials – but as a low-cost, readily available supplement without serious side effects, many owners have conducted their own tests of coconut oil on their dogs and are delighted with the results. With the exception of the studies on coconut oil and dogs with epilepsy, claims about what coconut oil can do for dogs are generally anecdotal reports shared by coconut oil enthusiasts rather than clinical trials and published studies.

That’s not to say it hasn’t been analyzed. Food scientists are aware that it contains medium-chain fatty acids, also known as medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). These fatty acids are metabolized differently from other fats as they go directly from the digestive tract to the liver, where they serve as a quick source of energy. The main MCT in coconut oil is lauric acid, which the body converts into monolaurin, which has antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal properties. Coconut oil’s other MCTs (caprylic acid, capric acid, and caproic acid) fuel the brain, help balance blood sugar levels, reduce chronic inflammation, and aid weight loss.

One group of dogs likely to benefit from coconut oil or MCT oil are those who have issues with fat, such as fat intolerance, high triglycerides, chronic pancreatitis, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). MCTs do not require pancreatic enzymes to be digested, so they are tolerated by dogs with those issues. This helps affected dogs avoid unwanted weight loss and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.

Reports of other promising studies about coconut oil and dogs with epilepsy:

“Efficacy of medium chain triglyceride oil dietary supplementation in reducing seizure frequency in dogs with idiopathic epilepsy” (Veterinary Record, October 31, 2020)

“A multicenter randomized controlled trial of medium-chain triglyceride dietary supplementation on epilepsy in dogs (Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, May 2020)

“Dietary medium chain triglycerides for management of epilepsy: New data from human, dog, and rodent studies” (Epilepsia, August 2021)

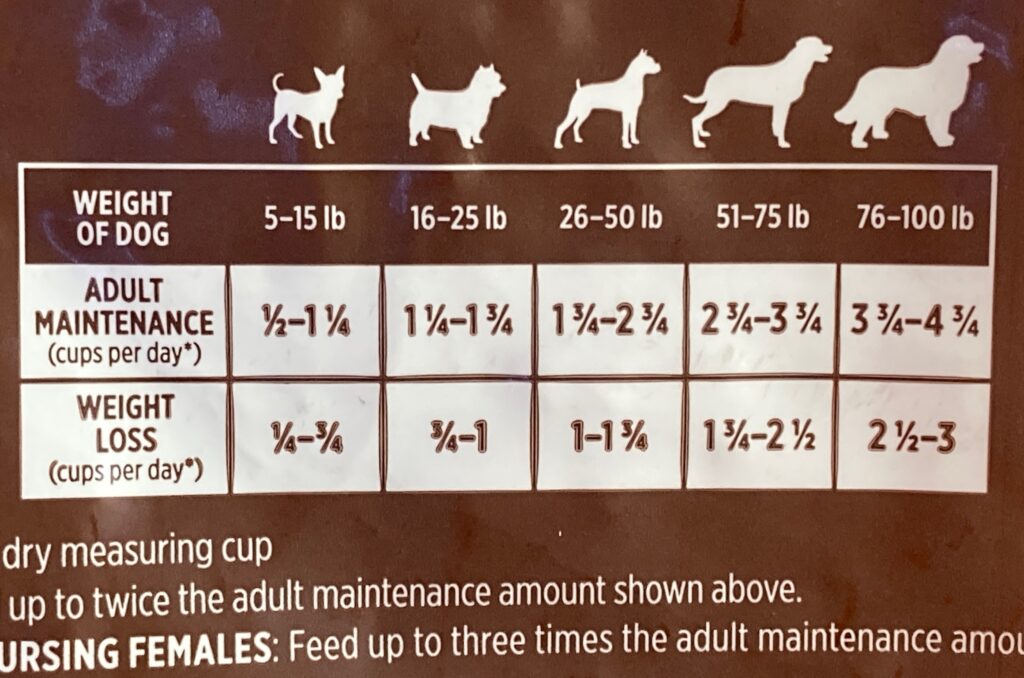

How much coconut oil can you feed your dog?

The recommended amount for most dogs is 1 teaspoon coconut oil per 10 pounds of body weight (1 tablespoon per 30 pounds body weight) daily.

Coconut oil contains 40 calories per teaspoon (120 calories per tablespoon), which can add up to more daily fat than an older, sedentary dog needs. Reduce the recommended dose to avoid unwanted weight gain.

However much you decide to feed your dog, begin with smaller amounts, such as one-quarter to half of the daily total. If your dog responds well, gradually increase the amount every few days until you reach the recommended dose.

If your dog experiences diarrhea when fed coconut oil, try dividing the daily amount into two servings.

Coconut additions to your dog’s diet aren’t limited to coconut oil. Most dogs enjoy pieces of fresh coconut directly from the shell as well as shredded dried coconut (no sugar added). Coconut water, the liquid inside a fresh coconut, is high in sugar and not usually recommended for dogs.

Is coconut oil safe for dogs?

Coconut oil is often criticized for its saturated fat content. In the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (September 2006), John Bauer, DVM, explained that saturated fats do not impart any increased risk of arterial diseases in dogs, in contrast to their effect in humans. Warnings about coconut oil’s saturated fats being dangerous to dogs are incorrect.

Coconut oil’s main adverse side effects when added to food are diarrhea and greasy stools. These are easy to prevent by feeding small amounts so the body can gradually adjust to the addition of coconut oil in the diet.

Some dogs are allergic to coconut products. Dogs who react by coughing, scratching, or showing other signs of discomfort may be responding to impurities in the oil, in which case switching to another brand may make a difference – or they may simply not do well with coconut oil and should avoid it.

How to apply coconut oil topically to your dog

For topical application, store coconut oil in a glass eyedropper bottle and a small glass jar. These containers are easy to warm in hot water to melt the oil if it’s solid.

Use the eyedropper to apply small amounts of coconut oil to ears, cuts, wounds, sores, or other targeted areas. Use the jar to apply coconut oil to larger areas, such as cracked paw pads.

Keep a towel or tissue handy to remove excess oil as needed. Because most dogs love the smell and taste of coconut oil, distract your dog or cover the treated area for a few minutes so the oil can be absorbed before your dog licks it off.

Choosing the right coconut oil

Once difficult to find, coconut oil is widely sold in supermarkets and natural food stores, with most of it coming from the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Mexico. Refined coconut oil (often labeled RBD for Refined, Bleached, and Deodorized) is made from copra (dried coconut meat) and treated to remove impurities. In most cases, the coconuts that produce it are of low quality and chemicals like chlorine and hexane are used in the refining process. This inexpensive coconut oil is safe for human and canine consumption, and it retains most of coconut oil’s healing benefits.

A better choice is unrefined or “virgin” coconut oil, which retains the nutrients found in fresh coconut; this is the first choice of most coconut oil enthusiasts. It is of higher quality and more expensive than RBD oil. For best results, look for cold-pressed (not heat-processed) raw coconut oil sold in glass rather than plastic containers.

Hydrogenated coconut oil, which is solid at temperatures below 92°F, contains harmful trans fats, and is not regarded as a health-promoting food.

Fractionated coconut oil is liquid at all times because it contains only caprylic and/or capric acid. Its lauric acid has been removed. Often labeled as MCT oil, this tasteless, odorless product is more expensive than regular coconut oil and is promoted as a nutritional supplement.

There are many coconut oils on the market and the quality varies. Try different brands to see what you and your dog most enjoy. Avoid any coconut oil that has a pronounced smoky odor or an “off” or rancid taste or fragrance, is yellow in color, or has any other discoloration.