You’re not likely to forget it if you’ve heard it even once: the half-cough, half-choke – sort of like a Canada goose in need of a Ricola lozenge – that signals your dog has come down with kennel cough.

As canine illnesses go, kennel cough has something of a split personality. Usually, it’s “self-limiting,” which means affected dogs generally recover without any interventions whatsoever, leaving the victim none the worse for wear. But every so often, a dog develops serious complications, necessitating hospitalization and extreme measures. Given that, plus the condition’s highly contagious nature, means that most boarding facilities and even veterinarians sometimes treat it with the kind of alarm usually reserved for an ebola outbreak.

Kennel cough is a generic name for a group of pathogens that produce a contagious upper-respiratory infection in dogs. Sometimes referred to as bordetella (one of the bacteria that can cause it), kennel cough is also called canine infectious respiratory disease (CIRD) as well as canine infectious tracheobronchitis. The abundance of names reflects the fact that kennel cough is really a loosely defined confederacy of viruses as well as bacteria, any of which can produce a cough that lasts from several days to weeks – and sometimes much longer, if complications such as pneumonia arise.

Kennel cough is spread through respiratory secretions, and since few dogs have learned the kindergarten trick of sneezing into the inside of their elbows, it can spread widely and quickly. As its name suggests, places where large numbers of dogs congregate can be a hotbed for spreading the disease, from boarding kennels to dog runs. Most dogs show symptoms within three to 10 days of exposure. In addition to the trademark gagging cough, infected dogs may exhibit sneezing, nasal discharge, and mild lethargy. Healthy adult dogs generally don’t otherwise act sick or stop eating, and likely will continue to play and be active, though physical exertion may trigger more hacking episodes.

In dogs who are very young, very old, highly stressed (for example, in a shelter), or immunocompromised, or who have an underlying condition, kennel cough can advance to the lower-respiratory tract and cause pneumonia, which is life threatening.

If this sounds like a wide range of symptoms, it may be because the illness actually is a range of illnesses, and caused by a variety of infectious organisms, bacterial and viral. (For the difference between kennel cough and canine influenza, as well as the newly identified circovirus, see sidebar.)

When she was a veterinary student more than 35 years ago, holistic veterinarian Christina Chambreau of Sparks, Maryland, did an externship at the National Institutes of Health’s foxhound breeding colony.

“My job for the summer was to do throat cultures on every coughing dog – and lots of them were coughing,” she remembers. “And every dog I cultured had a different combination of bacteria.”

At the same time, Chambreau worked part-time at a number of different veterinary clinics. “Each one had a completely different conventional treatment protocol – one used Prednisone, another used antibiotics, another said, ‘They’ll just get better.’ When you see multiple treatment protocols like that, it means none of them are ideal.”

Is it any wonder this condition is called the kennel cough complex?

Kennel Cough Vaccinations

For many conventional veterinarians, the reflexive answer to preventing kennel cough is to vaccinate for it.

Holistic veterinarian Marcie Fallek, who practices in both New York City and Fairfield, Connecticut, is not a fan of the vaccine, pointing out that it is short-lived and may not be adequately protective, as there is no way to cover all the pathogens that can cause kennel cough.

“It seems to cause disease more than prevent it,” she says, adding that facilities that insist on vaccinating new boarders on site are operating largely on reflex – and fear. And in reality, they aren’t doing a thing to protect their other clients.

“It takes several days, if not a week, for the kennel cough vaccine to be effective,” she explains. “So when you give it on the spot like that, it doesn’t protect the other dogs. If it’s going to give any protection, which is minimal, it’s only going to be the animal that receives it.”

Using this logic, some owners have persuaded boarding and day-care facilities to accept a signed waiver in lieu of a vaccine, agreeing not to hold them responsible should their dog contract the disease.

Veterinarian Jean Dodds of Garden Grove, California, says she “rarely” recommends vaccinating for kennel cough, because generally speaking kennel cough is “not a serious problem and the vaccines are not 100 percent efficacious.” But if an owner does decide to vaccinate, she does not recommend using the injectable form; instead, she recommends the intranasal vaccine, which is squirted up the dog’s nose, or the oral form, which is taken by mouth.

Intranasal vaccines for bordetella activate interferon, a pathogen-fighting protein, in the dog’s body, an action that does not result from injectable forms of the vaccine. “The interferon also helps cross-protect against other respiratory organisms,” says Dr. Dodds.

If you want to or need to vaccinate your dog for bordetella, it might make the most sense to ask your veterinarian for the intranasal bordetella vaccine that also contains a vaccine for CAV-2, a strain of canine adenovirus that affects the respiratory tract. A dog who is immunized against that form of adenovirus is also protected against the far more serious CAV-1, or infectious canine hepatitis, which can be life threatening. This might be unexpectedly welcome news to those who use minimal vaccination protocols that do not include canine hepatitis (including the popular one recommended by Dr. Dodds).

Dr. Dodds notes that, as with every vaccine, there are some dogs who react adversely to the kennel-cough vaccine, especially those with “a hypersensitivity-like response” in which the body responds to an immune challenge so severely that it can be life threatening. If your dog has had an adverse reaction to a kennel-cough vaccine, he should not be given any more of those vaccines for any reason.

For her part, Dr. Fallek recommends using a kennel-cough nosode, a homeopathic remedy that contains the energetic imprint of the disorder; while sometimes referred to as “homeopathic vaccines,” nosodes work differently, rebalancing the body rather than prompting it to mount an immunological attack. “Kennel-cough nosodes are not 100 percent protective, but neither are vaccines,” she points out. Dr. Fallek recommends that those who wish to use the nosode to protect a dog who will be in a high-risk environment start dosing the dog several days before the expected risk, giving the remedy once or twice a day with a 30C potency for a maximum of five days.

When it comes to preventing kennel cough, the best defense is, well, a good defense.

“The bottom line is, the healthier you can get your dog, the better,” Dr. Chambreau says. “You want to build the immune system so she fights it off herself.”

The basic building blocks of good health are just that – basic. Make sure your dog receives the best-quality food and water possible. Avoid and limit exposure to toxins. And pay attention to the early-warning signs that the body gives when it is beginning to weaken, but before disease manifests.

“These are little things your vet won’t think are wrong,” Dr. Chambreau says, including goopy discharge that accumulates in the corners of the eye, slight waxiness in the ears, a little red line in the gums, minor behavioral problems, and a slight overall odor that necessitates baths every couple of weeks. She recommends keeping a daily journal so you can see patterns in your dog’s well-being emerge over time.

“Any holistic treatment that builds the immune system will usually take care of kennel cough,” adds Dr. Chambreau, who is a staunch believer in what she calls “R&R” – a flower essence remedy called Rescue Remedy and reiki, a healing “life force energy” practice. “You take one course in how to do reiki, and you can start offering it to your dogs every day on a regular basis,” says Dr. Chambreau. And while Rescue Remedy and flower essences in general won’t cure kennel cough or any other disease, many dog owners report that these gentle plant distillations can center emotions and help alleviate anxiety or distress about kennel cough, as much for you as your dog!

Another thing you can add to your preventive toolbox is the thymus thump. During the early part of a dog’s life, the thymus programs the T-cells that are so central to the functioning of the immune system. “By tapping the thymus, you reactivate it,” Dr. Chambreau explains.

To find your dog’s thymus, run your hand down her throat, and below the throat feel for the firm, bony protuberance that is the sternum. Gently thump that area with your hand several times a day, or whenever you remember.

Quite an array of supplements, herbs, and tonics are reputed to help strengthen the immune system; the most commonly cited include coconut oil, apple cider vinegar, aloe vera juice, and whole food supplements.

Melissa Oloff of Canterbury, Connecticut, keeps her Ridgeback Coco on an immune-boosting regimen of Vitamin C and probiotics daily, as well as an echinacea capsule several times a week. When the doggie daycare that Coco attends had an outbreak of kennel cough, Oloff increased the frequency of administering echinacea, giving her dog a dose every day during the week when Coco was exposed. “She was fine, no symptoms,” Oloff says. “The kennel had to send home 50 percent of their dogs.”

Kennel Cough Treatment Plans

As Dr. Chambreau noted when she first began in veterinary medicine, conventional treatment for kennel cough varies, from simply keeping the dog quiet and avoiding drafts and strenuous exercise, to administering antibiotics (which are useless if the pathogen involved is a virus and not a bacterium). Some veterinarians may recommend a cough suppressant, but others, such as Dr. Fallek, contend that cough suppressants further weaken the immune system.

Dr. Fallek is trained in homeopathy, and she finds kennel cough relatively easy to treat with this energy-based modality. Though a dog’s individual symptoms should be used to select the correct remedy, one that Dr. Fallek finds works in many cases is Bryonia, which is indicated for coughs that are made worse by movement.

Dr. Chambreau, who is also a homeopath, notes that kennel cough often can be stopped in its tracks if the homeopathic remedy Aconite is administered at the very beginning. “If you find there is a remedy that works for you [the dog owner], then you might use that,” she says. “Often people and their animals need the same remedy.”

When kennel cough is a concern in Dr. Dodd’s facility (a canine blood bank, utilizing retired racing Greyhounds who are available for adoption!), Dr. Dodds brews a tea made of the herb mullein, which is used for calming the respiratory tract and treating lung ailments.

While mullein is not an endangered plant – the ultimate volunteer, it can get a roothold anywhere, including sidewalk cracks – some popular herbs are. Dr. Chambreau suggests substituting marshmallow root for slippery elm, which is being overharvested because of the popularity of its medicinal bark. As a bonus, marshmallow is the gentler of the two, while still providing soothing relief to inflamed mucous membranes. For throat soothing, Dr. Chambreau suggests aloe vera and raw honey.

Relationship between Canine Influenza & Circovirus

No matter what modality they use, Dr. Chambreau encourages owners to do their homework. No treatment is without its risks, and working with a trained practitioner is the best way to ensure that your healing intentions come to fruition.

If you spend any time on the Internet, you’ve come across frantic references to canine influenza and circovirus. There seems to be an inverse relationship between the hysteria that mention of these two viruses induces, and what people actually know about them. Let’s take the oldest one first.

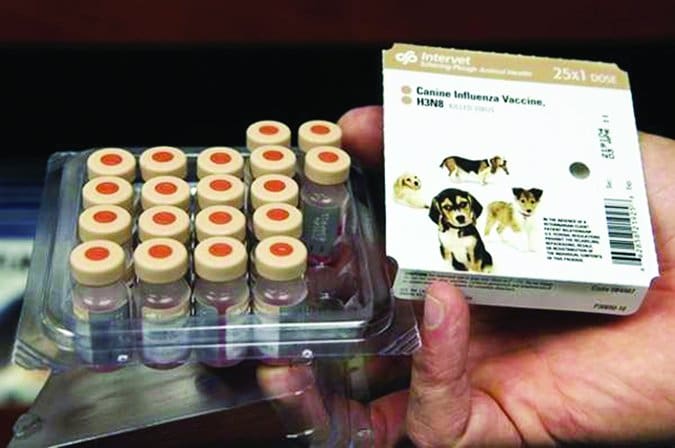

Canine influenza – specifically, canine influenza virus subtype H3N8 – first surfaced in a Greyhound kennel in Florida in 2004. A mutated version of a horse flu that “jumped species,” dog flu is highly contagious and produces symptoms that are similar to kennel cough – cough and runny nose. Dogs may also have a thick nasal discharge, which is usually caused by a secondary bacterial infection. But one thing that sets it apart, Dr. Dodds says, is the presence of a fever.

Like kennel cough, “canine influenza is generally not a disease of much clinical significance, despite the fact that it is a highly contagious virus,” says Dr. Dodds. For that reason, the canine influenza vaccine is not recommended for routine use, “except when animals may be exposed to high-risk situations such as crowded competitive show events, in which case it should be given prophylactically beforehand – two doses, three weeks apart.”

Dogs are at the greatest risk of complications if they become infected with the flu at a time when they are already coping with another stressor, such as intestinal parasites, malnourishment, or another infection.

“The only other dangerous scenario with this virus is when the dog has an upper or lower respiratory infection with streptococcus,” Dr. Dodds says. According to Ron Schultz of the Department of Pathobiological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, in that scenario, two to three percent of dogs infected with canine influenza and strep can die from the co-infection.

The latest panic-inducing virus is canine circovirus. Last fall, media reports about dogs who contracted some sort of lethal virus in Ohio, and then later, in Michigan, were thought to have suffered from circovirus. However, investigators later concluded that while some of the affected dogs were infected with circovirus, it was not the primary cause of their illness. In an update published in November, Thomas Mullaney, interim director of the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health at Michigan State University in Lansing, said, “Based on our current evidence, dog circovirus is not cause for panic.”

It is, however, cause for greater investigation. “I don’t think we really understand circovirus,” Dr. Dodds says. “It’s like giardia; it’s everywhere. What we don’t know is why it causes a major clinical problem in some dogs and not others.” There is also no vaccine for circovirus at this time.

Circovirus symptoms are more diffuse than those of kennel cough or canine influenza. They include vomiting, diarrhea (possibly bloody), and lethargy, though some dogs exhibit a respiratory component, such as coughing.

Researchers have been able to identify circovirus in lab samples from cases as far back as 2007. “The virus went undetected in dogs for several years and probably longer,” Mullaney wrote. “This supports the theory that dog circovirus exists as a subclinical infection, or as a co-infection with other well-recognized pathogens.”

Bottom line? Like kennel cough and canine influenza, circovirus isn’t a major problem for most dogs, but for some it will be. The best way to ensure that yours isn’t in the latter group is to keep her immune system robust and ready to meet the next challenge.

The Holistic Toolbox for Treating Kennel Cough

I’ve had dogs for most of my adult life, and I’ve dealt with kennel cough more times than I can count – though less and less as the years go by and I learn how to rear dogs with immune systems that can shrug it off. Like anything, how we choose to protect and treat our dogs is an evolution and a journey. Here’s where mine has taken me.

Early on in my life with dogs, I vaccinated for kennel cough. Until, that is, one of my fully vaccinated dogs picked it up at a show. Despite being put on antibiotics, he developed pneumonia, and though he recovered, his hospitalization left me with a whopper of a vet bill. I drew two conclusions from that experience: One, I needed pet insurance. And, two, maybe the vaccine wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

From that point on, I didn’t vaccinate for kennel cough (along with a lot of other things, but that’s a different story). I found that my young dogs tended to develop the most severe symptoms when they first encountered kennel cough, usually at a dog show. By contrast, my oldsters, with their wise and still vibrant immune systems, didn’t even sniffle.

After some trial and error, I came across what has become my go-to modality any time I hear that telltale hacking: the homeopathic remedy Drosera. Any time I administer it, the coughing stops in its tracks, and asymptomatic dogs in the household stay that way.

That said, I’ve talked to holistically minded folks who have had zero success with Drosera. One homeopath told me it has never worked for her, even though it is considered a potential remedy for kennel cough. Perhaps there is just something about me and my home that dovetails with Drosera energetically. Whatever it is, it has never failed me -with one exception.

Several months ago, I had a litter of puppies that was off to a shaky start. The dam had a Caesarian section, and the litter was less than half the size of a typical one for my girls: only four puppies, one of which faded hours after she was born. Less than a week later, Cocoa started hacking: It was kennel cough, picked up in those few hours at the vet’s office.

Trusty Drosera to the rescue: I dosed Cocoa, and her coughing stopped within hours. I dosed her babies, too, and, because I had never had puppies this young exposed to kennel cough – and none of my mentors or fellow breeders had, either – I started them on antibiotics.

(I feel a little self-conscious and even defensive about admitting here that I used antibiotics prophylactically, ven though I believe the decision to have been a correct, potentially even life-saving one; the small litter size and fading puppy suggested to me the possibility of a low-grade infection. But it says something about how militant “holistic medicine” enthusiasts can be when a conventional modality is chosen as a first course of action; sometimes we fall into the same reflexive judging that we complain about with an allopathic approach! And that’s not “wholism.”)

Several days later, the large male (who was so big and vigorous that we had dubbed him “Chubsy”) began making odd noises, which got worse if he moved around. Despite all my precautions, he had contracted kennel cough, and the noise I was hearing – sort of a snore, really – was a “stertor,” caused by a partial obstruction of the airway above the larynx.

Thankfully, Chubsy was still active and eating, and a quick vet visit showed his lungs to be clear. I consulted my copy of Boericke’s materia medica (a homeopathic encyclopedia) for other remedies that might help him fight off the kennel cough. But he didn’t improve.

After several days, I decided to switch to another modality I was comfortable with, essential oils, which shouldn’t be used in conjunction with homeopathic remedies because they antidote them.

I have had success staving off colds with Thieves Essential Oil. A proprietary blend of therapeutic-grade oils from Young Living, it’s named for the four grave-robbers of medieval legend who avoided contracting the plague from the cadavers they pilfered by swathing themselves in oils (that turn out to have antimicrobial properties). The oil is a wonderful immune booster; when colds and viruses make their wintertime rounds, I do family foot rubs of Thieves diluted in almond oil to keep us sniffle-free.

Mindful that essential oils can be very powerful, I used a diffuser to disperse the oil in the puppies’ room, for short periods several times a day. I watched the puppies and their mother closely for any negative reactions.

To the contrary: Chubsy improved almost immediately, and within a few days, all signs of the infection – including that sleep-anea-like stertor – had disappeared.

Thanks to that experience, I have another addition to my toolbox if kennel cough crosses my dogs’ paths again.

Denise Flaim of Revodana Ridgebacks in Long Island, New York, shares her home with three Ridgebacks, 10-year-old triplets, and a very patient husband.

This was the most helpful article I have read my toy Australian shepherd struggles with repeated cases of kennel cough his sister is full grown not a toy she has never gotten it. His snout is very narrow and he chokes every time he drinks water b/c his nose airways are so thin. Every time it starts to happen they tell me its no kennel cough but every test and chest x ray that has ever been done doesn’t show anything else and its the tell tale symptoms he gets it about 4 to 6 times a year and it starts with a reverse sneeze and he cannot breath and his nose and his eyes drip so they said he has allergies but then comes a cough and the thickest white foam stuff you can imagine . I just don’t understand why he continues to get this I am worried one day its going to kill him b/c he cannot breathe. I am going to try all of the above recommendations. right now he is on antibiotics and the only thing that helps is half of a cough tablet so he can rest .

Are you familiar with or ever used Lomatium. This is my family’s go to for just about everything especially viral and bacterial.