In January 2010, a massive earthquake rocked the West Indian island of Hispaniola, bringing the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince to its knees as hundreds of thousands of people were missing or feared dead amid the destruction.

As myriad relief teams sprung into action, some of the most highly skilled members hadn’t yet reached a double-digit birthday, worked with enthusiastic barks and tail-wagging, and were happiest with “paychecks” they could tug.

They were urban search and rescue dogs, many of whom were trained at the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation in Santa Paula, California.

One Woman’s Vision

The National Disaster Search Dog Foundation is the brainchild of Wilma Melville. It started when her retirement hobby as a civilian canine search-and-rescue handler took her to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in the wake of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building bombing in 1995. At the time, Melville and her canine partner were one of only 15 canine teams certified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in the entire country. As she debriefed from the experience, she decided there had to be a better way to develop qualified teams capable of meeting FEMA standards, and one short year later, the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation (NDSDF) was born.

Today, the foundation trains about 20 dogs per year, placing the canine graduates with approved first-responder handlers all around the country. Canine candidates are recruited almost exclusively from dogs living in shelters and with rescue groups. A network of trained canine recruiters research and evaluate prospects from across the country. Approximately 30 to 40 dogs find their way each year to the foundation, where they are further evaluated for acceptance into formal training. Dogs not accepted for formal training, or who are released from training at any point, are either placed with qualified families as part of the organization’s Lifetime Care Program, or helped into a different working dog career.

“It’s important to us to use re-homed dogs; it’s simply the right thing to do,” says Sylvia Stoney, NDSDF’s manager of canine recruitment. “There are so many dogs who need a job – a purpose – and so many of these dogs possess the qualities we look for that make them the perfect candidates for our training program.”

Indeed, the qualities of a good search dog frequently misalign with many pet owners’ idea of a good family dog. A dog with the right amount of intensity and perseverance needed for life-saving search work is often very challenging in a pet home. A good search dog doesn’t just love toys. Rather, he has an “obsessive, visceral response to a toy, and an insatiable desire to chase, hunt, and possess it.” This is not the dog whose behavioral needs are met by a daily walk around the neighborhood, some basic training, and a backyard game of fetch.

“Where one person might see destructive energy, we see a great opportunity to redirect that energy into a fun game of hide-and-seek,” explains Stoney.

In search-and-rescue training, the “victim” is hidden with the beloved toy and the dogs are taught to locate the victim’s scent and bark to alert the handler. Upon finding the victim, the dog is rewarded with an exciting game of tug. It’s all a fun game to the canine heroes!

Expecting the Unexpected

One of the biggest challenges facing search-and-rescue canine teams is the ability to train under a range of circumstances that even remotely mimic what they will encounter at an actual disaster site.

“You’re often at the mercy of concrete recycling centers, but that only gives you rubble search,” says Debra Tosch, the foundation’s program and finance administrator, and a former FEMA-certified canine-search specialist. “Maybe you can get access to a building with furniture, but nothing is overturned, so you aren’t really working under realistic conditions.”

Tosch and her canine partner Abby’s first deployment was the World Trade Center collapse on 9/11/01. Because all of their training had been at recycling centers or other pristine, by comparison, sites, Tosch initially worried about her dog’s ability to navigate the complex labyrinth of twisted steel that stood before them. “I’d never seen my dog work on anything like that,” she says.

Fortunately, Abby’s training carried her through the challenging searches. But for Tosch, the experience emphasized the need for a more realistic training center where teams would gain more real-world experience.

“It’s very important to be able to remove questions of, ‘I wonder if my dog can do this?’ and allow handlers to show up feeling like, ‘I know my dog can do this!'” Tosch says.

Disneyland for Dog-and-Handler Teams

In 2009 the foundation broke ground on what would become a first-of-its-kind, 125-acre National Training Center (NTC) solely dedicated to the training of canine disaster-search teams. Nestled deep in the Santa Paula foothills, about 90 miles from Los Angeles, the state-of-the-art center connects teams from around the country with skilled professional trainers while they face complex search tasks – scenarios that far exceed what can be staged at typical training sites.

“When the teams come out here, we challenge them. We don’t set them up to fail, but we challenge them. Then they take what they’ve learned back to the team and share with other handlers on their task forces,” says Tosch. “We really want these teams to be prepared when that call comes and they head out the door. That’s how you strengthen disaster response in America.”

There is no shortage of challenges to be had at the training site, which features areas that are dedicated to different types of disasters in varied locations. Elements were designed with input from working handlers who recalled what they found most challenging about various deployments.

“Search City” is currently comprised of multiple buildings, including a convenience store filled with overturned shopping carts (a complex agility challenge) and a two-story tilted house, with rooms in various states of disarray, designed to elicit feelings of vertigo in the human handlers as they accompany their canine partners. It also includes three Hollywood back-lot-style building facades (a schoolhouse, a firehouse, and a townhouse), each with its own debris pile.

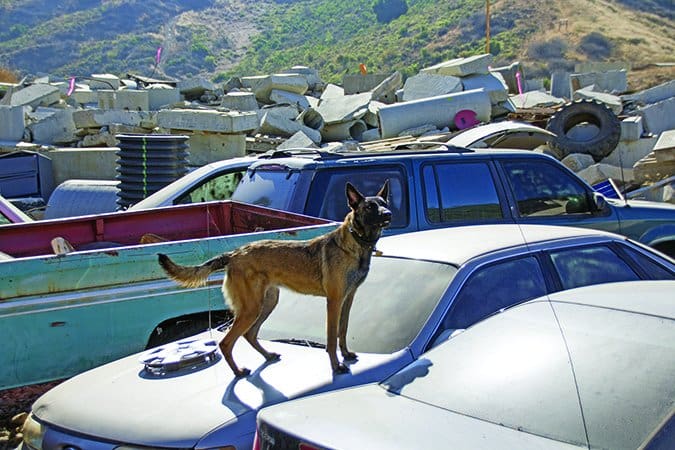

“Industrial Park” is home to a two-car train wreck and simulated freeway bridge collapse. Overturned cars, abandoned RVs, mountains of wood pallets, and the occasional small airplane litter the area. A 10,000 square foot rubble pile rounds out the currently available elements, and a tower where teams can learn to rappel with their dogs is also in the works. Tosch says the exact layout of the elements is expected to change quarterly, allowing teams who visit repeatedly to face new challenges each time.

One of the most interesting features of the NTC is its use of a proprietary scent-delivery system that can deliver live human scent to various places within the buildings, even to locations where it does not appear a human could be. For example, as the victim is stationed in a small outbuilding, his scent can be delivered to a specific area, such as underneath a bathtub in a Search City building. Seeing the dog alert on the bathtub drain can confuse the handler, often leading him to believe his dog is incorrect. Foundation trainers oversee the exercise and validate the dog’s alert when needed, reminding handlers to trust their dogs.

“As humans, we’re visual. The dog might be barking and be totally on the scent, but the handler is using his eyes and thinking there’s no way someone can be there,” explains Tosch.

The NTC is also equipped to house handler teams in its 24-bed handler lodge. The lodge helps cut travel-related costs for out-of-area teams and allows teams to train for longer hours, over multiple days, a common real-world experience. This helps teams build the endurance necessary to maintain motivation throughout a mentally and physically challenging search.

In its mission to strengthen disaster response in America, the NDSDF makes training at the NTC financially accessible to teams from all around the country. In addition, its highly trained dogs are placed with approved first-responder handlers at no cost. The entire operation is funded exclusively by corporate and private sponsorships and donations; the Foundation receives no government funding.

The NDSDF is Well Received

Teresa MacPherson’s first glimpse of the NDSDF training center was via helicopter, as she and her task-force canine handler teammates were air-lifted into position – another element of “realness” made possible thanks to the foundation’s commitment to authenticity. MacPherson, a civilian member of FEMA’s Virginia Task Force 1, helps evaluate and train other teams, which allows her to travel to a variety of training sites, often with her dog. Still, she was thrilled to get the chance to experience the National Training Center.

“It’s a really cool site,” she says. “They were able to surprise me, they really made me think, and they challenged my dog with a lot of complex scent pictures and agility scenarios. I’ve done a lot of training, but this was really challenging. We have to expose our dogs to all kinds of different scenarios in training so it all comes together and, when we hit ‘the big one,’ the dogs aren’t surprised, they’re prepared.”

Firefighter Captain Jason Vasquez of the Los Angeles County Fire Department and a member of California Task Force 2, agrees that the NDSDF’s center strengthens the skill set of the dogs trained there. Vasquez has a long history with the foundation. He received his first foundation-trained canine partner in 2004 and has been partnered with two more foundation-trained dogs since then. Vasquez says the growth of the NDSDF, including the development of the National Training Center, has created better prepared, more sophisticated handlers through the creation of an in-depth handler’s course and continuing education opportunities.

“The handlers are 100 percent more advanced from when I started,” he says. In the past, the task force would recommend a team member to be partnered with a dog, but the team member often didn’t begin learning his full range of handler responsibilities until after he was paired with a dog. Now, handlers begin learning about their role as early as six months prior to placement, and they attend a two-week handler’s course at the foundation. This shift has led to less handler washout and a better FEMA certification success rate.

For Vasquez, the biggest advantage of the National Training Center is the diverse collection of training scenarios. Not only are the scenarios challenging, thanks to the creative expertise of the on-site training staff, but they consist of elements that are difficult, if not impossible, to otherwise access. For example, Vasquez says West Coast teams are often known for being especially skilled on rubble piles, as they are readily available. On the other hand, building searches are harder to come by, as the area’s homeless population often overruns abandoned buildings. Conversely, East Coast teams are known for being especially good at building searches, but they often lack access to rubble piles. “At the training center, you have both. We can take advantage of things we don’t otherwise have access to and we can access a lot of different training elements in one stop,” he says.

From Grassroots to a Leadership Role

As the foundation continues its mission, another goal is to develop a deployment readiness certification designed to help task forces determine whether or not their certified teams are deployment ready.

“The FEMA certification is the minimum standard needed to go out the door with a task force,” says Tosch. “Certification tests the minimum skills required to certify on that particular day, but certification is not deployment.”

According to Tosch, FEMA certification is important, but can’t be an accurate assessment of deployment readiness, because it doesn’t adequately recreate the complex mental and emotional challenges of deployment. The foundation’s goal is to create an assessment that would provide teams with a more realistic picture of the myriad challenges – for both dogs and handlers – that exist while on a mission.

“It’s so impressive to look at where the foundation started, and to see where they are today,” Vasquez says, noting the much-appreciated ability of the organization to maintain a grassroots feel and foundation-family atmosphere.

“That’s one of the reasons I keep coming back. I’m proud of my canine partner and I’m proud to be part of such a great organization,” he says.

SEARCH AND RESCUE DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Support the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation in its mission to strengthen

disaster response in America. More funding means more trained dogs are paired with first responders, potentially saving lives when disasters strike.

2. Be sure your shelter knows about the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation in the event they might have a candidate dog.

3. Learn more about the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation. You can even request a tour of the National Training Center.

Stephanie Colman is a writer and dog trainer in Southern California.