Heartworms are just what they sound like: worms, up to 14 inches long as adults, that develop and live within the blood vessels of the dog’s heart. Though they prefer the right side of the heart, in a severe infection, they also develop and live within the lungs or any major artery – wherever they can find room with access to blood.

Heartworm disease refers to the constellation of ill effects the dog suffers as a result of this population growing inside him. Heartworm disease has the highest morbidity and mortality of any insect-transmitted disease in the United States.

At one point, heartworm disease was considered a problem of certain areas (the Southeast is notorious for this), changes in climate, dogs being moved across state lines (for instance, dogs relocated from Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina), and changes in wildlife territories have all led to fluctuations in the distribution patterns of the disease. As a result, heartworm disease in dogs is no longer limited to particular parts of the country.

The good news is that with the advent of modern parasiticides and routine surveillance (testing for heartworms), heartworm disease can be prevented. If prevention is not taken and a dog becomes infected with heartworms, he can be treated for the infection – but the treatments can pose a risk to the dog. Prevention is the best approach!

What Happens During a Heartworm Infection in Dogs

Dogs become infected with heartworms through the bites of infected mosquitoes. A mosquito who has taken a blood meal from an infected canid (dog, coyote, wolf, fox) transmits heartworm larvae into the next canid it bites.

The microscopic heartworm larvae enter the dog from the mosquito’s mouthparts and begin a developmental journey that sees them progress through several larval forms and migrate into the dog’s bloodstream, looking for a hospitable place to attach and grow into adult worms.

The pulmonary arteries where the adult worms ultimately lodge become inflamed, dilated, and malformed, as the heart labors to push blood past the obstructing worms. Blood clots and aneurysms (a dangerously ballooning bulge in a blood vessel) can develop.

The heavier the heartworm “burden” – the more worms that the dog is infected with – the worse the dog’s symptoms and prognosis will be. Dogs can become infected with so many parasites that the heartworms can obstruct the flow of blood through the heart, leading to dilation and thickening of the laboring muscles of the right side of the heart. The thickened heart muscle is subject to disturbances in the electrical impulses of the heart, leading to arrhythmias.

If the worm population is unchecked, the heart becomes too distorted to function at all, and the dog can suffer right-sided heart failure. Or, “caval syndrome” may be observed, where the entire right side of the heart is filled with heartworms, interfering with closure of the tricuspid valve and impeding the flow of blood through the heart, leading to cardiovascular collapse.

As the heartworm infection progresses, the blood vessels of the lungs (pulmonary vasculature) become inflamed and unhealthy. This causes pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs). And as the worm-laden heart has to work harder, it becomes less able to pump blood throughout the body, driving the acquisition of oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide in the lungs. As this progresses, the dog becomes increasingly intolerant of exercise – or, in severe cases, any movement at all. The dog will develop a chronic cough that worsens over time, and the dog’s belly may become distended with fluid (ascites).

The heart, lungs, and even the kidney and liver eventually show signs of disease – all caused by the increasingly inefficient labors of the burdened cardiovascular system.

Caval syndrome is an uncommon but lethal condition in which a massive clot of worms suddenly obstructs the vena cava (a large vein that carries blood into the heart). This occurs when a dog has a heavy infection of adult heartworms and it leads to immediate, life-threatening shock. A dog will collapse, have pale gums, rapid heart rate, and fast, irregular breathing. Bloody urine can develop, and body temperature may be low.

There is only one successful treatment for this condition, and it is invasive and risky. It involves making a cut into the jugular vein and manually removing the clot of worms from the heart with long forceps.

Once enough worms are removed, the heart can pump efficiently again. This treatment requires general anesthesia while a dog is in a state of shock, as well as 1 to 2 days of hospitalization for recovery followed by adulticidal treatment. The prognosis is extremely guarded.

The Range of Heartworm Symptoms in Dogs

It usually takes at least a year before a dog, bitten by an infected mosquito, shows signs of heartworm disease – and it may take even longer. The symptoms that dogs may display as a result of their heartworm infection depend on a number of factors:

- How many heartworms a dog becomes infected with (dogs can be infected with just one worm or dozens; the worms don’t increase in number without repeated, new infections caused by bites from more infected mosquitoes).

- The exact location in the dog’s circulatory system where the worms attach themselves (worms lodged near heart valves, for example, can cause more trouble than ones elsewhere).

- How long the worms have been present in the dog (the longer, the more damage they can cause; worms can live up to 5 to 7 years and grow 12 inches or longer).

- The dog’s health (some dogs may better tolerate a limited infection than others).

Early signs of a heartworm infection in dogs may be a mild cough or “slowing down” during exercise (exercise intolerance). You may notice that your dog becomes reluctant to run and play or tires quickly, particularly in the heat. A dog who is only lightly infected (with just one or two worms) may never experience worse symptoms than this.

However, dogs who have a heavier worm burden and/ or become repeatedly reinfected will suffer worsening and serious symptoms. Eventually, total failure of the right side of the heart occurs. Blood-tinged fluid may drip from the nose. Dramatic weight loss called cardiac cachexia can be noted. This is end-stage heart failure and successful treatment is difficult. At this stage, death is not far off.

Heartworm Lifecycle

To understand how best to prevent and treat heartworm infections, it helps to understand the life cycle of the heartworm.

The heartworm goes through several physical transformations in its lifetime and requires hosts of two different species to complete its life cycle: the mosquito and a mammal. The life cycle starts in an infected animal. If an adult male and a female adult heartworm are both present in a dog, they can produce microfilaria, a type of motile embryo. The microfilariae circulate freely in the infected animal’s blood and cannot develop any further unless they are sucked up into a mosquito through its bite.

The next stages of a heartworm’s development can take place only in the gut of a mosquito – weird, right? Once a mosquito ingests a blood meal laden with microfilariae, the microfilariae start to mature. Over a period of 10 to 30 days (average is about two weeks), the microscopic embryos develop through three larval stages – still very microscopic, but each distinct. If the mosquito bites another dog, any larvae in the third stage of development (called L3 larvae) exit the mosquito through its mouthparts and enter the dog. Only once the L3 larvae are in a mammal again can they develop further.

The larvae live and continue to develop in the dog’s subcutaneous tissue for about 50 to 70 days, in a stage called L4 – the fourth larval stage. Once that stage is complete, the larvae begin to migrate through the dog’s tissues, in search of the circulatory tract. Once they reach a blood vessel and enter the bloodstream, they become sexually immature adults. These juvenile worms move toward the heart and lungs, where they latch on and mature into sexually capable adults who can mate, so the females can produce viable embryos (microfilaria), starting the life cycle again.

This entire process, from the bite of the mosquito who takes the microfilaria from an infected dog, through the larval stages in the mosquito, through the larval stages in a new mammal host, to adulthood, takes a minimum of about six months.

It’s important to understand this cycle, as veterinary technology can prevent your dog’s infection, or, failing that, detect his infection in order to deliver a timely treatment, at specific times in the heartworm’s life cycle, and under specific conditions.

Heartworm Prevention for Dogs

Heartworm preventative drugs belong to a class of medications called macrocyclic lactones. They have been in existence for about 30 years and are derived from the soil microorganism Streptomyces.

Macrocyclic lactones are used in both the treatment of human and animal parasitic diseases. These medications work by inhibiting nerve transmission within parasites, leading to their paralysis and death. They effectively kill the third-stage larvae that infected mosquitoes may have newly implanted in your dog, as well as the fourth-stage larvae that are developing under his skin.

These drugs do not kill any juvenile or adult heartworms that may already reside in the circulatory tract (though the drugs may weaken them). Once the larvae reaches the bloodstream, it’s too late for the preventative drugs to kill them. To be effective, the drugs must be administered between the bite of an infected mosquito and when the larvae reaches young adulthood. That’s why these drugs must be administered precisely on the schedule recommended by their manufacturers (monthly for many of the drugs, or according to label instructions).

Heartworm Preventative Medications

| Heartworm Preventative | Active Ingredients | Form | Effective Against | Duration | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage Multi | imidacloprid, moxidectin | topical | heartworms, adult fleas, sarcoptic mange mites, roundworms, hookworms, whipworms | 30 days | Bayer |

| Heartgard | ivermectin | oral | heartworms | 30 days | Boehringer Ingelheim |

| Heartgard Plus | ivermectin, pyrantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms | 30 days | Boehringer Ingelheim |

| Interceptor Plus | milbemycin, praziquantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms, whipworms, tapeworms | 30 days | Elanco |

| IverHart Max | ivermectin, pyrantel, praziquantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms, tapeworms | 30 days | Virbac |

| IverHart Plus | ivermectin, pyrantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms | 30 days | Virbac |

| ProHeart 6 | moxidectin | injection | heartworms | 6-12 months | Zoetis |

| Revolution | selamectin | topical | heartworms, fleas, ear mites, ticks, sarcoptic mange mites | 30 days | Zoetis |

| Sentinel Flavor Tabs | milbemycin, lufenuron | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms, whipworms, fleas | 30 days | Virbac |

| Sentinel Spectrum | milbemycin, lufenuron, praziquantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms, whipworms, tapeworms, fleas | 30 days | Virbac |

| Simparica Trio | sarolanar, moxidectin, pyrantel | oral | heartworms, ticks, fleas, roundworms, hookworms | 30 days | Zoetis |

| TriHeart | ivermectin, pyrantel | oral | heartworms, hookworms, roundworms | 30 days | Merck |

| Trifexis | spinosad, milbemycin | oral | heartworms, fleas, hookworms, roundworms, whipworms | 30 days | Elanco |

How to Diagnose Heartworm

Most dog owners have had their dogs tested for heartworm infections, but many are unaware of the limitations of these tests.

The most sensitive and readily available antigen detection test is a snap test that can be conducted in your vet’s office. A blood sample is drawn, mixed with a conjugate solution, and applied to the test. Results are available within 10 minutes.

The most common heartworm tests used by veterinarians detect the antigens that are released by adult female heartworms into the dog’s bloodstream. In most cases, antigen tests can accurately detect infections with one or more adult female heartworms.

Currently there are no USDA-licensed serologic tests that can detect male heartworms. This means if a dog, by chance, is infected with only male heartworms, the test won’t catch it. And if a dog is infected, but the heartworms have not yet reached adulthood, the test won’t catch it.

Also, if a dog is infected with just one or two adult female heartworms, the tests will detect antigens produced by this tiny female population only 60% to 70% of the time. The dog may test negative or inconsistently positive.

In addition, according to Michael W. Dryden, DVM, MA, PhD, of the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, recent studies have documented that antigen tests may not test positive in up to 7% of dogs due to the occurrence of “antigen-antibody complexes” that are formed in the dog’s blood.

So, to counter these rather sobering testing statistics, in an ideal world, puppies would be started on heartworm preventative medication at their first veterinary visit, and receive their first heartworm tests at or just before a year of age. Since tests cannot detect heartworms before the heartworms are 6 to 7 months of age, there is little reason to test much sooner. (That said, if I was looking at a rescued dog of indeterminate age who lived primarily outside before rescue, especially in a warm climate where mosquitoes are active year-found, I would test him sooner.)

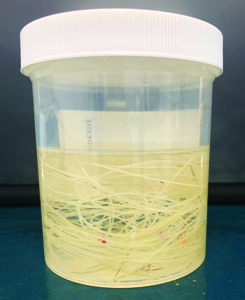

Your veterinarian might also look at a blood sample under the microscope. The microfilariae are easy to detect, as the active embryonic larvae are much bigger than blood cells. They also “whip” from side to side. A positive antigen test and the presence of microfilaria definitely means that a dog has a heartworm infection.

If the antigen test is positive, but no microfilariae are detected, then a second heartworm test should be conducted to confirm the positive finding. Treatment for the infection should not be started until the positive has been confirmed.

If a dog tests negative but has symptoms compatible with heartworm disease and hasn’t been taking prevention, then more extensive testing is necessary. This includes a blood smear to look for microfilaria as mentioned above. “Heat fixation” is a newer test, conducted by outside laboratories, that can dissociate the antigen-antibody immune complexes, unbinding any heartworm antigen present so that it is detectable by the antigen tests.

If you choose to import a dog from another state, make sure that he has been thoroughly examined and tested for heartworms – both so he can be treated promptly and to eliminate the possibility that he provides a new local reservoir (host) for heartworms in your area.

Some breeds of dogs, particularly white-footed herding breeds such as Australian Shepherds and Collies, are known to have a deficiency of P-glycoprotein. This is known as the multi-drug resistant mutation (MDR1). Dogs with this mutation are unusually sensitive to certain classes of drugs including macrocyclic lactones (MLs).

However, studies have shown that at the standard preventive doses, MLs are safe in all breeds. This is why it is important to use the canine products rather than trying to dose large animal products. The vast majority of toxicities in MDR1 mutation dogs were caused by overdose of large animal products or accidental ingestion of too much medication.

Heartworm Treatment Options

If a heartworm infection is confirmed, the next step is determining how advanced the disease is. This can include x-rays of the chest to look at the dog’s heart size, lungs, and blood vessels.

Some veterinarians will also conduct an electrocardiogram (ECG) to evaluate the heart rhythm for abnormalities, as well as an echocardiogram – an ultrasound of the heart. This will determine if the heart is enlarged, and heartworms will show up on the echo as bright white lines. Knowing the severity of disease can predict the likelihood of complications from treatment.

Dogs with minimal cardiovascular changes have a good prognosis. The presence of heart failure, significant lung changes, and caval syndrome complicates treatment significantly.

The treatment of heartworm infections has advanced significantly in recent decades.

Initially, oral prevention such as milbemycin is administered for two months, along with doxycycline. The oral prevention kills the larval forms and any circulating microfilariae that may be present. (The microfilariae can’t develop into heartworms in your dog – but you don’t want your dog to be a host for any stage of the heartworm life cycle!)

Doxycycline is an effective antibiotic against Wolbachia, a parasite harbored within the heartworm. By killing the parasites in the heartworms, the heartworms themselves are weakened. When administered as part of therapy, doxycycline lessens the complications of infection.

At two months (day 60), it’s time to administer melarsomine (Immiticide), the drug that actually kills the adult heartworms. The drug is given as an injection deep into the epaxial muscles along the spine on days 60, 90, and 91. During treatment, extremely strict crate rest with or without sedation and close monitoring are required.

A dog’s prognosis depends on the severity of infection at the time of treatment, as well as the management of the dog during the treatment period. As the worms die, they decompose in the bloodstream. If a dog exercises enough to elevate his heart rate, severe complications such as worm or pulmonary embolism (blood clot) leading to respiratory distress and collapse can occur. Treatment for embolism is hospitalization for oxygen therapy and steroids to decrease inflammation in the lungs. Many dogs will do well if this is caught and treated quickly. But it can’t be repeated enough: It’s critical to strictly control the dog’s activity while he undergoes treatment for heartworm infection.

Other helpful medications include steroids to reduce inflammation as the worms die, as well as pain medication to alleviate discomfort caused by the deep intramuscular injection of melarsomine. Sedatives may be needed to keep a dog rested, calm, and exercise-restricted. According to the American Heartworm Society, “A pivotal factor in reducing the risk of thromboembolic complications is strict exercise restriction.” An antihistamine may also be administered to reduce the risk of anaphylaxis.

Monthly preventative medication is the most effective way to prevent canine heartworm infections, but here are a few more:

• Eliminate sources of standing water in your dog’s environment. Ask your local or county mosquito abatement manager what you can do to control mosquitoes.

• Minimize your dog’s time outdoors at prime mosquito feeding hours (dawn, dusk).

• Make sure to administer preventions monthly and use only those specific to canines. Do not use large animal products as it is easy to mis-dose these and cause toxicity.

• If any doses of preventative are missed, contact your veterinarian to discuss appropriate next steps.

“Slow Kill” Method

The so-called “slow kill” method of treating a heartworm infection consists of a monthly dose of heartworm preventative medication only; no adulticidal medications are used. Remember, the preventative medications kill any circulating microfilariae as well as any L4 forms of the parasite. But these medications don’t quickly or reliably kill the adult heartworms that damage the dog’s circulatory and pulmonary systems, though they do weaken the adult worms and shorten their life span. The result is that the heartworms may take as long as two years to die, as opposed to a couple of months.

A 2004 study examining the efficacy of the slow-kill method determined that nearly 30% of dogs still tested positive on a heartworm antigen test after 24 months of monthly heartworm prevention.

Finally, the slow-kill method may not destroy a subpopulation of worms that are resistant to the medication, leading to a worse infection that cannot be treated with macrocyclic lactones.

A slow-kill protocol is inexpensive in terms of money spent by the dog’s owner, but very costly in terms of the dog’s health. Dogs being treated in this way must be strictly rested to prevent the risk of pulmonary blood clots caused by the breakdown of dead heartworms. As long as the heartworms are alive, pathologic changes to the lung and heart tissue continue, and this damage is usually permanent.

In contrast, the conventional treatment has been shown to clear heartworm infections 98% of the time – and within a couple months of starting the treatment protocol.

The Takeaway Message About Heartworm

Heartworm disease is a serious, often fatal syndrome. Prevention is simple! Administer monthly prevention to protect your dog, minimize mosquitoes in your environment, and work closely with your veterinarian to develop a healthy lifestyle.

Are you aware every single time a potentially L3-laden mosquito bites your dog? Of course not; no one is. That’s why the preventative drugs are delivered monthly – to kill any larvae that may have been deposited in your dog in the last month, before any of them can develop into mature heartworms and take up residence in your dog.

With the understanding that heartworm infections start with mosquito bites, some dog owners limit the administration of heartworm preventative drugs to seasons when they can witness the presence of mosquitoes; for example, they may stop giving preventative drugs in fall and winter. Some owners feel their dogs are so rarely outdoors, or that their climate is so mosquito-free, they don’t need to give their dogs heartworm prevention.

As a veterinarian, I’ve heard these reasons and more. Some of my clients have told me that they live in an area with a particularly low endemic rate of infection or that they’ve never personally experienced heartworm in previous pets. They may also have concerns about the cost of preventative drugs or fear adverse side effects from the administration of preventives.

According to the American Heartworm Society, “Heartworm disease has been diagnosed in all 50 states, and risk factors are impossible to predict. Multiple variables, from climate variations to the presence of wildlife carriers, cause rates of infections to vary dramatically from year to year—even within communities. And because infected mosquitoes can come inside, both outdoor and indoor pets are at risk.”

With rare exceptions, all dogs should be on heartworm prophylaxis (preventative drugs) year-round. Puppies should be started on these medications as early as possible. There are oral, topical, and injectable options on the market, so administration has never been easier. These are weight-based medications and will be adjusted as your dog grows.

Many prescription heartworm preventions also treat intestinal parasites such as roundworms and hookworms. Some also prevent whipworms and tapeworms. A few are now combined with flea and tick prevention. By administering these medications, you keep your pets healthy, as well as yourself and family members. Some intestinal parasites are zoonotic to people, including hookworms, tapeworms, and roundworms. Children are particularly susceptible.

To help you make the decision whether to administer heartworm medications, the American Heartworm Society website provides valuable insight on rates of infection in your state, as well as zoomed-in views of certain local areas. There are incidence maps available for the United States, helpful infographics, and even an area just for kids. Go to www.heartwormsociety.org.

There are many prescription options on the market, and your veterinarian will likely only carry some of these. Discussing your lifestyle and preferences with your veterinarian can help determine which works best for you and your dog. But you need to use something!

Thank you for this great article. One thing I’m curious about is the long-term damage. My cocker spaniel was rescued and before we got her she was treated for heartworms. We don’t know the extent of the damage.

Thank you for the information on heartworms. I really learn somethings I didn’t know

Can someone explain what’s the difference between whipworms and tapeworms.

Why would dogs need to be on Hw preventative during the winter months?

They don’t need to be on meds in the winter months but the manufacturers in collaboration with veterinarians want owners to think that they do. As my vet explained to me when I asked her this question: If the temperature rises during the winter (I live in a moderate climate area but the winter is cold enough such that there are no mosquitoes) such that some mosquitoes hatch then your dog is at risk.

I stopped giving heartworm meds a long time ago because we don’t have mosquitoes at any time of the year where I live. I suppose that is because there is a vector control program but probably of more significance is that I live in an area where there is no rain at all in the summer. Consequently very little standing water in the warm months. Every once in a while we will have a few mosquitoes but statistically speaking, I think it more dangerous to give poison to my dogs then to buy into the propaganda that my dogs are in danger. I do test with SNAP every 6 months and have never had a positive test. Our neighbor’s dogs live outside and they are also negative.

They don’t need to be on meds in the winter months but the manufacturers in collaboration with veterinarians want owners to think that they do. As my vet explained to me when I asked her this question: If the temperature rises during the winter (I live in a moderate climate area but the winter is cold enough such that there are no mosquitoes) such that some mosquitoes hatch then your dog is at risk.

I stopped giving heartworm meds a long time ago because we don’t have mosquitoes at any time of the year where I live. I suppose that is because there is a vector control program but probably of more significance is that I live in an area where there is no rain at all in the summer. Consequently very little standing water in the warm months. Every once in a while we will have a few mosquitoes but statistically speaking, I think it more dangerous to give poison to my dogs then to buy into the propaganda that my dogs are in danger. I do test with SNAP every 6 months and have never had a positive test. Our neighbor’s dogs live outside and they are also negative. If I was traveling with my dog to the mountains, however, I would absolutely get a Rx and use the heartworm meds. When mosquitoes are present, I absolutely do believe that the benefit to risk ratio of the meds is favorable.

I live in an area with historically low HW rate BUT have noticed a few mosquitoes this winter. Therefore, I made an informed decision to place my two MDRI mutant/normal Collies on Interceptor thanks to this article which served as a foundation to further research. Even if I had MDR1 mutant/mutant Collies, Interceptor would have been safe. Let’s hope these heartworm medications remain effective vs. HW developing resistance. Anyhow, thank you for covering this topic. With climate change, pests are finding new domicles. My area is warmer and wetter.