By Randy Kidd, DVM, PhD This has become a nation of fat people – and fat dogs. Once again our dogs are mirroring us, no matter how bad that picture looks. It has been estimated that (depending on the survey and the way “obese” and “overweight” are defined) from about 25 percent to more than half of dogs seen by veterinarians are overweight or obese, and many practitioners feel that even these numbers grossly underestimate the true extent of the problem. For more perspective we can refer to numbers from a medical database maintained by Banfield, The Pet Hospital (a chain of 500-plus veterinary hospitals). Its data indicate that of the 3.5 million animals seen in the chain’s hospitals each year, almost 83 percent are categorized as exceeding their recommended weights. More worrisome, the obesity trend seems to be accelerating in recent years, much as it has in humans. The percentage of heavy dogs seen at Banfield increased from 49 percent to 83 percent from 1999 to 2004. The problem of defining obesity in dogs stems in part from the wide variance that exists in “normal” weights for different breeds. Most fat experts define an “overweight” dog as being 10 to 15 percent above the ideal weight for the breed; an animal is obese when he weighs 15 to 25 percent or more than the breed’s ideal weight. Another way to look at obesity is to look at it structurally rather than limit its definition to a set weight standard. Under this guideline, obesity can be defined as an increase in body weight beyond the limitation of its skeletal and physical requirements, resulting from an accumulation of excess body fat.

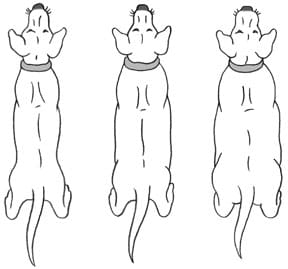

Whatever the definition and true statistics are for overweight and obese dogs, obesity is the most common nutritional disorder in dogs, and many practitioners feel it is today’s number one health danger for dogs. According to existing statistical evidence, the increased incidence of obesity (in both dogs and humans) has dramatically risen only over the past 10 years or so. Obesity is a, well, growing problem without an end in sight. And for fat people and fat dogs, this is not a good sign. It is interesting to note that it is not just dogs and their people that are overweight; overweight and obese cats are also a concern, and the Banfield survey mentioned above found that many exotic pets – birds, ferrets, and rabbits – are overweight too, again with the percentages of overweight animals increasing over the past few years. Being fat is not healthy Obesity in dogs may be associated with the following diseases: hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus, non-allergic skin conditions, arthritis, and lameness. Increased weight puts added stress on bones and the ligaments and tendons of joints, making them more susceptible to traumatic injury. Fat dogs don’t ambulate as well; they become couch potatoes, resulting in “stuck” joints that cause the dog to want to lie about even more – a cycle that ultimately leads to a painfully immobile animal. The immune system is compromised when an animal is overweight, making him more susceptible to infections and autoimmune diseases. Being overweight adversely affects the intricate balance of many, if not all, the body’s hormonal systems, resulting in any number of hormonally related diseases. Being overweight also adversely affects the skin; overweight animals typically have dull, lusterless skin that is in turn more susceptible to disease processes. No matter how you look at it, the obese animal has a poorer quality of life than his trimmer counterpart. He also actually has a shorter life. Purina Pet Institute’s 14-year study showed that dogs who ate 25 percent less food than their well-fed counterparts in the study lived longer – on average 13.5 years, compared to the average age of death of 12.2 years for their chubbier trial mates. In addition, the less-stuffed dogs had fewer signs of aging (grey muzzles, etc.) and a much lower incidence of hip dysplasia than did the overfed dogs. My dog, fat?! Determining this may take more than a good long look at the dog. In the first place, folks who are overweight tend not to see the fat in front of their eyes. Many studies have shown that most overweight folks don’t realize they are carrying excess baggage, and other studies indicate that folks who are overweight also tend to have overweight pets – and they don’t recognize the added pounds in either themselves or their pets. Another problem is that dog breeds have so many distinct body types it is often difficult to see through the normal body type into the fat of the matter. There is help, however, and it comes in two forms: a body condition score, developed by Purina, and the availability of an unbiased opinion. The body condition score (BCS) is a chart that provides a numerical ranking from 1/emaciated to 5/obese for dogs and cats. (1 = emaciated; 2 = thin; 3 = moderate; 4 = stout; 5 = obese.) The chart is easily accessible on the Internet, and it comes complete with examples of how the typical animal within each ranking would appear. Most veterinary clinics also have a copy of the chart for easy viewing. The best way to use the chart is to first compare your dog to the chart and then use your hands to feel for body condition. A fit dog should have an indented waist and the waist line should tuck-up slightly behind the ribs. (Remember that some breed standards may vary somewhat from this ideal.) Dogs tend to put on fat over their shoulders, ribs, and hips and around the tail head. You should be able to feel individual ribs and the space between each rib, and the shoulder blades, hips, and tail head should be readily palpable. Since folks tend not to notice just how fat they or their animals are, it’s probably a good idea to get an unbiased opinion – check with your vet, and ask for an honest fat appraisal. One caveat here: It may be best to have a thin and fit vet do the evaluating; out-of-shape vets might also tend to overlook fatness in their patients, and they will almost certainly minimize the importance of exercise for overall health. There are also several newer ways to evaluate the fatness of your dog that may prove to be more valid than the more subjective BCS. Leptin is a peptide hormone synthesized and secreted primarily by fatty tissue. Increased plasma levels of leptin correlates with body fat, probably better than either body weight or the BCS. There is now a simple blood assay for leptin that may prove useful for quantitative obesity assessment in small animals. Other methods of assessing body fat that are more hi-tech (and usually more expensive) include ultrasonography, bioelectric impedance (determines the amount of various body fluids as well as measuring leanness); DEXA scan (Dual Energy X-ray Absortiometry – determines bone mineral content and density, muscle mass, and percent of body fat), and the D2O dilution method (deuterium oxide dilution – determines total body water, a measurement of body fat). How obesity happens In dogs (and their people) obesity has become a health problem of epidemic proportions. The solution to the problem of fat dogs can actually be reduced to a simple equation (more exercise; fewer calories). But there are many instigating factors associated with obesity. A truly holistic approach to keeping your dog’s weight within its ideal range will consider these, along with an exercise program and a diet that provides the requisite number of calories for the amount of “work” the dog does. Specialists in bariatric medicine – the study of overweight, its causes, prevention, and treatment – feel that obesity may have numerous causes that can loosely be categorized into: environmental, behavioral, available foods, and biological components. So far, bariatric medicine is primarily a human specialty (one could predict that the specialty will soon develop in veterinary medicine), but many of its methods can, by extension, be applied to animals. In fact, some of the work that is used to help define and treat human obesity was originally done on laboratory animals, including dogs. There are at least two potential obesity-causing components of the environmental factors to consider: the dog’s social environment and his physical environment. The number one cause of obesity in our dogs is humans. “Over-love” is an important part of why our dogs are overeating; we want to make them happy! They beg, and we reinforce the behavior (making it more likely to happen again) by feeding them. The more they beg, the more we feed them, the more they beg – and the weight goes on. Giving our dogs treats – often as we wolf down a fatty, carb-loaded, nutritionally empty treat ourselves – has become an American way of life. There’s another social aspect to overeating: often, in multiple dog families, the presence of other dogs encourages some of them to overeat. Apparently the social aspect of being in a “pack” of dogs creates the competitive desire to wolf down the available food before the other dogs can get their fair share. A dog’s social environment is also an important consideration for how much he will weigh as an adult. Every practitioner will tell you that the fat dog often has a fat person at the other end of the leash. The way we humans have adapted our physical environment is also involved in our pet’s propensity to be fat. In a few short decades we have moved from a mostly rural population to a society where most of us live in cities or suburbs. Back when I started veterinary practice, the greatest majority of the dogs who visited my practice could be considered “free range” dogs – they were country dogs with several acres to roam over, or they had an in-town backyard to play in that would be considered huge by today’s standards. Today’s dogs are often enormous dogs, kept in small apartments, and their backyard “playground” is the size of a postage stamp. Further, the art of walking and chatting with the neighbors has been lost – and along with it, the evening walkabout that once upon a time gave the family dog some time to stretch out, run around, and rub noses with the other neighborhood dogs. Our own sedentary lifestyle and the way we have sardined ourselves into a living environment surrounded by concrete has made it difficult for us to help our dogs get the amount of daily exercise they need. Recent surveys show that even when folks know full well that they are overweight, that their dogs are overweight, and that exercise is the answer to the problem, they still will not take the time to walk their dogs the 150 minutes per week that is considered the minimal time necessary for maintaining body condition. There’s more: One theory says that pollutants in the air may be partly responsible for obesity. Organochlorines are fat-soluble chemicals that are almost ubiquitous in today’s environment – they are a continuing contaminant in our air, coming from a variety of sources including the outgassing of plastics (such as polychlorinated biphenyls, PCBs) and pesticides such as chlordane, aldrin, endrin, dioxin, dieldrin, and DDT/DDE. Their presence may be related to a biochemical process that results in weight gain in animals.

The organochlorine (OC) theory basically works like this: Obese animals have higher concentrations of OCs in their bodies. With weight loss, the blood concentration of OC increases as they are released from fatty tissue. An increased blood OC level has been associated with reduced fat oxidation, reduced resting metabolic rate, and reduced skeletal muscle oxidative capacity (reduction in the muscle’s ability to work and use up calories) – all these effects may be due to a decreased effectiveness of the thyroid gland. The end result is that as the animal loses weight, he releases OCs from fat reserves into the blood, which decreases his ability to metabolize carbohydrates effectively … which ultimately allows the weight that he has lost to return as weight gain. All this spells yet another reason to avoid pesticides whenever possible, and to avoid plastics if possible – for example, use glass or stainless steel feeding and watering bowls instead of plastic ones. Lots of contributors For eons the canine species roamed the forests and fields, hunting and scavenging for whatever morsel of food they could find. Being a carnivore is hard work, sometimes exciting in the extreme, and it takes a certain amount of skill to fill one’s belly with any regularity. For our pets, all that is gone now; the only effort and skill required is the ability to find the food dish. And the food dish is mostly filled with processed carbohydrates, not the meaty proteins a dog’s digestive system is adapted for. And so, our obese dogs have reason to blame the foods they eat for some of their problems. Many commercial pet foods, over the years, have increased dietary fat levels and improved the palatability of their foods. Most commercial foods simply contain too little meat-derived protein, too many grain-based carbohydrates, and too much fat. Fat adds to a food’s palatability and, in the case of kibble, is sprayed onto the extruded food so the dog will eat it. Just as their human counterparts, dogs vary widely in their level of physical activity and in the amount of food they want to eat each day. Since these behaviors are innate, the best we can do is to notice them and then offer compensatory actions to counteract their tendency to create an overweight dog. For instance, most Border Collies will probably not need to be encouraged to exercise more; they tend to be hyperactive enough. A pooch who wants to sleep all day, however, may need a little encouragement to get into his daily walk. You may be able to appease the dog who is a perpetual beggar by feeding him very small amounts of food several times a day, being sure that the total amount of food stays within the recommended amount of calories for the dog’s ideal weight. Again, like their human counterpoints, dogs have a wide range of resting metabolic rates. Those with a high metabolic rate can seemingly eat anything and everything and never get fat; the animal saddled with a low metabolic rate can literally look at food and get fat. The key is to recognize these differences and to compensate for the dog with the low metabolic rate by limiting his daily food intake and being certain he is getting enough exercise. • Spaying and neutering: Both of these two operations have an effect on the animal’s potential for future weight gain. Information (from Ohio State University) indicates that when an animal is spayed or neutered, his or her energy needs decrease by about 25 percent. Other factors that add to a spayed or neutered animal’s propensity for weight gain include: a) lack of roaming – males, especially, don’t roam as much after neutering; b) no expenditure of energy for reproduction, gestation, and lactation; and c) perhaps the most important, an owner who has demonstrated his devotion to the dog by having him or her neutered or spayed; owners who care may also be the type who simply must feed a begging dog treats throughout the day. The bottom line here is that spayed or neutered animals will not get fat just because they lack their gonads. True, they will likely need fewer calories, after the surgery – but so long as they are fed foods that provide them with some caloric reduction, and so long as they continue to exercise adequately, they will not gain weight. • The genetic hypothesis: Some breeds of dogs, including Labradors, Golden Retrievers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Cairn Terriers, Basset Hounds, Shetland Sheepdogs, Dachshunds, and Beagles tend to be more prone to obesity. While the genetic hypothesis has merit, not all dogs with genetic susceptibility to obesity become overweight, and any individual of any breed of dog or mutt will become obese if he is fed too much for the energy he expends. It should also be noted that in humans there have been several gene-loci identified as associated with obesity, and each of these loci has in turn several additional, associated genes that have been identified as contributing to the overall propensity for the individual to be obese. In other words, genes may be important, but trying to find the one that is the contributor to obesity is like searching for one particular flake of Parmesan in the spaghetti sauce. • Age: As an animal ages, his metabolism slows, and often creaky joints and the simple lack of a burning desire to chase all things interesting can lead to a diminished expenditure of calories. The result can be a gradual increase in weight – unless we watch the calories and decrease them as the animal ages. • Stress: Chronic stress can have a huge impact on a dog’s weight. Stress causes the adrenals to secrete excess amounts of glucocorticoids that alter glucose metabolism, which (via a complex of enzymatic and hormonal reactions) ultimately leads to an accumulation of body fat. In addition, stress can lead to alterations in the homeostatic systems of the body to the extent that other diseases occur. • Diseases: It’s been estimated that diseases account for less than five percent of the total number of cases of obesity in humans, and a like percentage probably occurs in dogs. In reality, it is often impossible to determine which comes first: the disease causing the obesity, or the obesity precipitating the disease. Diseases that may be associated with obesity in dogs include: hypothyroidism, Cushing’s (hyperadrenocorticism), diabetes, insulinoma (tumor of the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas), and diseases of the pituitary. The “cure” As you’d expect whenever you have a disease process that counts so many patients, there are a plethora of “cures” for obesity on the market. Seemingly, humans will try anything – from crazy diet plans, to stapling their stomachs, to filling themselves with non-nutrients to create a sense of satiety. Drugs abound: drugs to increase metabolism (amphetamines and others); drugs to stop the absorption of fats; drugs to fool the brain into thinking the belly is full or into thinking its caloric needs have been met, and on and on. None of these high-tech solutions to obesity have worked long-term in humans or animals – unless the intervention is coupled with long-term social and behavioral modification and most importantly unless an adequate amount of weekly exercise (approximately 150 minutes per week) is included in the program. There are several diet foods available in today’s marketplace, and these often combine a lowered amount of carbohydrate, low fat (5 to 8 percent dry matter basis), and a food source with increased levels of fiber (10 to 25 percent dry matter basis). A reducing diet should begin with a goal that recognizes the animal’s ideal weight compared to the standard for its breed or type. A program of gradual weight reduction – somewhere between 3 to 5 percent of body weight per week initially and about 1 percent of body weight per week as the dog nears ideal weight. The amount of weekly weight loss to shoot for will depend on the current weight of the animal, his age, and general health. To achieve this weight reduction, the diet should provide enough food to meet about 50 to 70 percent of the requirements for the animal’s ideal or normal weight. Instead of one or two daily meals, small meals may be fed frequently during the day, and snacks and table foods should be eliminated entirely. The burden of resisting a constantly begging dog can be lessened by feeding small amounts (1 tablespoon or so) several times a day and carefully monitoring future food allotments once the desired body weight is attained. It may be best to have a veterinarian monitor the animal’s progress on a monthly basis – again because folks are often too close to their animals to see that they are overweight, and it can be difficult for many of us to create an environment of tough love. One study, for example, showed that caretakers who were allowed to institute a diet program on their own were unsuccessful (probably too many treats given to the begging dogs on the side); whereas the same diet, monitored by a veterinarian, produced the expected weight loss during the time frame of the trial. There is evidence that acupuncture may be effective for helping to reduce weight. Acupuncture is evidently extensively used to aid weight reduction in China; it operates by enhancing the digestive system, thus making nutrients more bioavailable and quenching the desire to overeat. Remember, too, that acupuncture and chiropractic will help keep your dog’s joints “oiled,” and thus make it easier for him to get out and about every day. Some herbs have also shown some promise for helping an animal reduce its weight – when they are combined with a long-term program of behavioral modification and exercise. Due to the recent interest in an easy-fix for fatness, the list of weight-reducing herbs has become endless, but some of the following may be helpful: aloe vera, astragalus, chickweed, dandelion, fennel, fenugreek, green tea, plantain or psyllium, red pepper, and Siberian ginseng. Check with an experienced herbalist for dosages and methods of use for these herbs. One of the more promising of the weight-loss supplements for dogs appears to be DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone), although its popularity for weight reduction in dogs has come as the result of one study only. Animals in this study were fed a high-fiber, low fat diet, with half of them receiving high doses of DHEA. All dogs on the study lost weight, but the dogs fed DHEA lost almost twice as much – 10 percent vs 5.5 percent. Several years ago DHEA was a popular human supplement, used as the cure-all for aging, among other things, but it went out of favor when it was discovered it also had some adverse side effects. So, to my way of thinking, the jury’s not yet out on DHEA for dogs; check with your holistic vet. Simple, if you can do it Today’s sophisticated science often overwhelms common sense and rational thinking, and thus we have come up with a variety of reasons to explain why our dogs (and ourselves) are getting progressively fatter. While some of these explanations can be used to help prevent obesity in predisposed animals, most don’t offer us much more than an excuse for feeding our dogs unhealthy foods or for not exercising adequately. The real answer to the problem is to feed fewer calories, especially empty calories, and to exercise more. Couple this with an environment that values fitness and a life-style that enhances playful interaction with other critters (four-legged and two-legged) and you have all the prescription you and your dog need for staying fit and trim. -Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.