Chippy, our Toller, is a terrible food thief. (Of course, the use of the word terrible is one of perspective. Given his impressive success rate, Chippy would argue that he is actually a very good food thief). He’s an incredibly sweet-looking dog; just don’t turn your back on your toast. Or any delicious food! Chip has become so proficient at his food thievery that our dog friends all know to “keep eyes on Chippy” whenever we celebrate a birthday or have snacks after an evening of training. We are often reminded of the now-infamous “birthday cake incident” during which Chip and Grace, an equally talented Aussie friend, succeeded in reducing a section of cake to mere crumbs, no evidence to be found. Suffice it to say, we watch food in our house.

Like many other expert food thieves, Chip is quite careful in his pilfering decisions. He will steal only when we are not in the room or when we are being inattentive. The parsimonious (simplest) explanation of this is a behavioristic one: Chip learned early in life that he was more likely to be successful at taking forbidden tidbits when a human was not in the room, and more likely to be unsuccessful if someone was present and attentive to him. In other words, like many dogs who excel at food thievery, Chip learned what works!

However, while a behavioristic explanation covers most aspects of selective stealing behavior in dogs, a set of research studies conducted by cognitive scientists suggest that there may be a bit more going on here.

Do Dogs Have a “Theory of Mind”?

Many dog owners can attest to the fact that dogs will alter their behavior in response to whether a person is actively paying attention to them or is distracted. For example, in separate studies, dogs were more apt to steal a piece of food from an inattentive person, and would preferentially beg from an attentive person. (Cited references1,2)

One could explain this in very simple terms, based on well-established observations about how animals learn. For example, a dog could learn over time that human gaze and attentiveness reliably predict certain outcomes, such as positive interactions and opportunities to beg for food. Similarly, a lack of eye contact and attention might reliably predict opportunities to steal a tidbit (or two or five).

But it’s also possible that, just like humans, dogs use a person’s gaze to determine what that person does or does not know. This type of learning is considered to be a higher-level cognitive process because it requires “perspective-taking”- meaning that the dog is able to view a situation through the perspective of the human, and can then make decisions according to what that individual is aware of. The import of this type of thinking is that it reveals at least a rudimentary “theory of mind” – the ability to consider what another individual knows or may be thinking.

So, while it’s established that dogs are sensitive to the cues that human eye contact and gaze provide, it’s not clear whether they can use this information to determine what the person may or may not know.

Enter the cognitive scientists!

The Toy Study

Here’s one approach to teasing out “theory of mind” evidence: Researchers set up a scene that causes the test subjects to change their behavior based on the inferences they draw from watching another being, whose own view of the scene is limited. They wanted to see what a dog does when he can see that a human may or may not be able to see what the dog sees.

In 2009, Juliane Kaminski and her colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology set up a clever experiment (reference 3) in which they used a barrier that was transparent on one end and opaque on the other end. A dog and a human were positioned on opposite sides of the barrier, and two identical toys were placed on the same side of the barrier as the dog. The dog was then asked to “Fetch!” They found that the dogs preferred to retrieve the toy that both the dog and the person could see, over the toy that only the dog could see.

The results suggested that the dogs were aware that their owners could not know that there was a toy located out of their view, and so retrieved the toy that they (presumably) assumed that their owner was requesting.

An additional finding of this study was that the dogs were capable of this distinction only in the present, at the time that the owner’s view was blocked. When the researchers tested dogs’ ability to remember what the owner had been able to see in the past, such as a toy being placed in a certain location, the dogs failed at that task.

Food Thievery Study

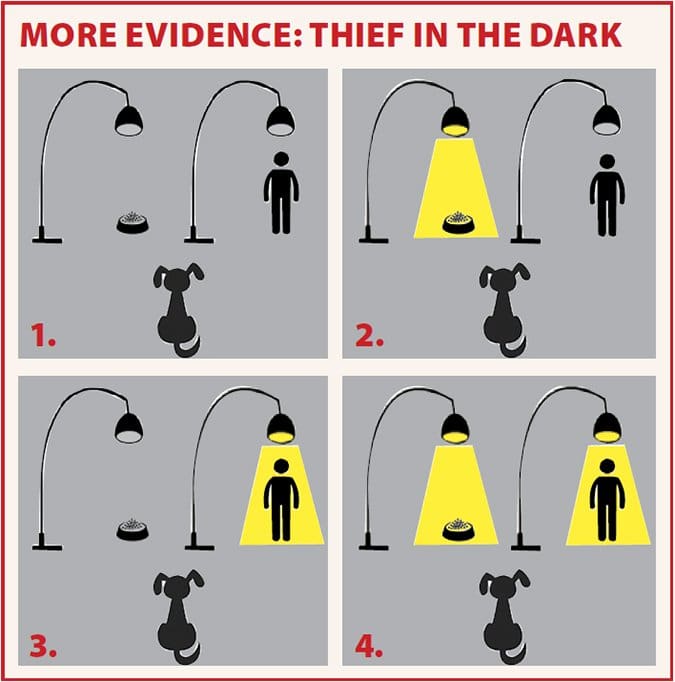

Recently, the same researchers (reference 4) provided additional evidence that dogs are able to consider what a human can or cannot see. Twenty-eight dogs were tested regarding their tendency to obey a command to not touch a piece of food under various conditions; the variation had to do with the commanding human’s ability to see the food.

The testing took place in a darkened room that included two lamps, one of which was used to illuminate the experimenter and the second to illuminate a spot on the floor where food was placed. During the test conditions, the experimenter showed a piece of food to the dog and asked the dog to “leave it” while placing the food on the ground. The experimenter alternated her gaze between the dog and the food as she gradually moved away and sat down.

In two subsequent experiments using the same design, the experimenter left the room after placing the food, and the degrees of illumination were varied. For each experiment, four different conditions were tested, and the dog’s response with the food in each set of conditions was recorded. The conditions were:

1. Completely dark; both lamps off

2. Food illuminated, experimenter in the dark

3. Experimenter illuminated, food dark

4. Both food and experimenter illuminated

There were several illuminating results in this study (sorry, I could not resist this opportunity to make that pun):

1. Dogs steal in the dark.

When the experimenter stayed in the room, dogs were significantly more likely to steal the food when the entire room was in the dark. (They do have excellent noses, after all). If any part of the room was illuminated while the experimenter was present, the dogs were less likely to steal. Conversely, when the experimenter was not present, illumination made no difference at all and most of the dogs took the food. (Lights on or off; they did not care. It was time to party!)

2. Smart dog thieves work fast.

Within the set of dogs who always took the food, when the experimenter was present, they grabbed the tidbit significantly faster when it was in the dark, compared to when the food was illuminated. This result suggests that the dogs were aware that the experimenter could not see the food and so changed up their game a bit. (“I’ll just weasel on over to the food and snort it up, heh heh. She can’t see it and will never know. I am such a clever dog!”) Chippy would love these dogs.

3. It’s not seeing the human that matters, it’s what the human sees.

Collectively, the three experiments in the study showed that illumination around the human did not influence the dogs’ behavior, while illumination around the food did (when a person was present). This suggests that it is not just a person’s presence or attentiveness that becomes a cue whether or not to steal, but that dogs may also consider what they think we can or cannot see when making a decision about what to do.

Take Away Points

Without a doubt, gaze and eye contact are highly important to dogs. They use eye contact in various forms to communicate with us and with other animals. We know that many dogs naturally follow our gaze to distant objects (i.e., as a form of pointing) and that dogs will seek our eye contact when looking for a bit of help. And now we know that dogs, like humans and several other social species, can be aware of what a person may or may not be able to see and, on some level, are capable of taking that person’s perspective into consideration.

As a trainer and dog lover, I say, pretty cool stuff indeed. Chip, of course, knew all of this already.

Just One More Thing

I was excited about this research because these results continue to “push the peanut forward” regarding what we understand about our dogs’ behavior, cognition, and social lives. Learning that dogs may be capable of taking the perspective of others, at least in the present, adds to the ever-growing pile of evidence showing us that our dogs’ social lives are complex, rich, and vital to their welfare and life quality.

That said, because these studies had to do with dogs “behaving badly” – i.e., “stealing” food – I was a bit hesitant to write this article. These studies provide evidence that dogs have a lot more going on upstairs than some folks may wish to give them credit for. And as can happen with these things, evidence for one thing (understanding that a person cannot see a bit of food and so deciding to gulp it on down), may be inappropriately interpreted as evidence for another (“Oh! This must mean that dogs understand being ‘wrong!’). Well, no. It does not mean that at all.

If you have ever thought, “My dog knows he was wrong!” or “I trained him not to do that; he is just being willful!” or “He must be guilty; he is showing a guilty look!” – then I have a message for you: These studies show us that dogs understand what another individual may and may not know, based upon what that person can see. This is not the same, or even close to being the same, as showing that dogs understand the moral import or the “wrongness” of what they choose to do. Chippy knowing that I cannot see that piece of toast that he just pilfered is not the same as Chippy feeling badly that he took it. (For more on this, see “Debunking the Myth of the ‘Guilty Look,’ ” WDJ October 2015.)

The bottom line: These studies show us that dogs may be sneaky, but neither the studies nor the results say anything at all about whether the dogs feel guilt when they sneak a bite of food they’ve been told to leave alone.

Linda P. Case, MS, owns AutumnGold Consulting and Dog Training Center in Mahomet, Illinois. She is the author, most recently, of Beware the Straw Man (2015) and Dog Food Logic (2014), and many other books about dogs. Check out her blog at thesciencedog.wordpress.com.