[Updated December 26, 2018]

I just talked to a potential client who is interested in bringing his 7-month-old Golden Doodle to train with us at AutumnGold. His dog, Penny, has the usual young dog issues – jumping up, a bit of nipping during play, still the occasional slip in house training, etc. Penny also raids the kitchen garbage bin, removing and shredding food wrappers, napkins, and any other paper goodies that she can find. The owner tells me that he is particularly upset about this last behavior because he is certain that Penny “knows she has done wrong”. He knows this because . . . wait for it . . . “Penny always looks guilty when he confronts her after the dreaded act.”

If I had a nickel . . . !

Like many trainers, I repeatedly and often futilely it seems, explain to owners that what they are more likely witnessing in these circumstances is their dog communicating signs of appeasement, submission, or even fear.

And, also like many other trainers, I often feel as though I am beating my head against the proverbial wall. But wait! Once again, science comes to our rescue! And this time, it is a darned good rescue indeed.

The guilty look is a difficult issue to study because it requires that researchers identify and test all of the potential triggers that may elicit it, as well as the influence the owner’s behavior and his or her perceptions of their dog may have. Tricky stuff, but lucky for us, several teams of researchers have tackled this in recent years, using a series of cleverly designed experiments.

Is it scolding owners? The first study, published in 2009, was designed to determine if dogs who show the “guilty look” (hereafter, the GL) are demonstrating contrition because they misbehaved, or rather are reacting to their owner’s cues, having learned from previous experience that certain owner behaviors signal anger and predict impending punishment.1

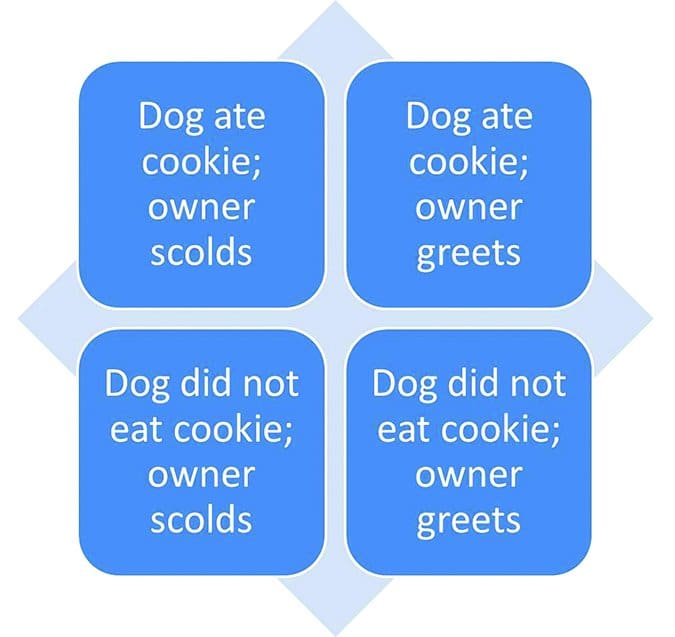

The study used a 2×2 factorial design, in which dogs were manipulated to either obey or disobey their owner’s cue to not eat a desirable treat, and owners (who were not present at the time) were informed either correctly or incorrectly of their dog’s behavior. The box below illustrates the four possible scenario combinations:

Study 1

Fourteen dogs were enrolled and all of the testing took place in the owners’ homes. All of the owners had previously used “scolding” to punish their dogs in the past; an additional one in five also admitted that they used physical reprimands such as forced downs, spanking, or grabbing their dog’s scruff. In addition, all of the dogs were pre-tested to ensure that they had been trained to respond reliably to a “leave it” cue and would refrain from eating a treat on the owner’s instruction.

During each test scenario, the owner placed a treat on the ground, cued the dog to “leave it,” and then left the room.

While the owner was out of the room, the experimenter picked up the treat and either (1) gave the treat to the dog or (2) removed the treat.

Upon returning to the room the owner was informed (correctly or incorrectly) about his or her dog’s behavior while he or she was away. Each dog was tested in all four possible combinations. (For a detailed explanation of these procedures and controls, see the complete paper listed in “Cited References” at right). Test sessions were videotaped and dogs’ responses were analyzed for the presence/absence of behaviors that are associated with the GL in each of the four situations.

The Results – Two important results came from this study:

1. Scolding by the owner was highly likely to cause a dog to exhibit a GL, regardless of whether or not the dog had eaten the treat in the owner’s absence.

2. Dogs were not more likely to show a GL after having disobeyed their owner than when they had obeyed. In other words, having disobeyed their owner’s cue was not the primary factor that predicted whether or not a dog showed a GL.

First nail in the coffin: The owner’s behavior can trigger the GL.

What about dogs who “tell” on themselves? Joe next door, who happens to know a lot about dogs, says, “How do you explain my dog Muffin, who greets me at the door, groveling and showing a GL, before I even know that she has done something wrong?”

Not to worry; the scientists got this one, too.

Study 2

Experimenters set up a series of scenarios involving 64 dog/owner pairs.2 The testing took place in a neutral room with just one dog, the owner, and one researcher present. After acclimatizing to the room and meeting the experimenter, the dog was cued by the owners to “leave” a piece of hot dog that was sitting on a low table. The owner then left the room.

In this experimental design, the experimenters did not manipulate the dog’s response. Instead, they simply recorded whether the dog took the treat or not. But before calling the owner back into the room, the treat (if not eaten) was removed.

The owners then returned to the room but were not informed about what their dog did (or did not) do in their absence. The owner then was asked to determine, by his or her dog’s behavior whether or not the dog had obeyed the “leave it” cue. In this way, the experimenters ingeniously tested for the “dog telling on himself” possibility.

The Results – Just as the first study found, a dog’s behavior in the owner’s absence was not correlated with showing a GL upon the owner’s return. Corroborating evidence from independent studies is always a good thing!

The researchers also found that when they controlled for expectations, owners were unable to accurately determine whether or not their dog had disobeyed while they were out of the room, based only upon the dog’s greeting behavior. In other words, the claim that dogs tell on themselves and therefore must have an understanding that they had misbehaved was not supported.

Second nail in the coffin: Dogs don’t really tell on themselves; it’s an owner’s myth!

The most recent study, published in 2015, parsed out a final two factors that could be involved in the infamous GL: the presence of evidence as a trigger and guilt itself.

If indeed, as many owners insist, a dog’s demonstration of the GL is based upon the dog having an understanding of the “wrongness” of an earlier action, then this would mean that the trigger for the GL would have to be directly linked to the dog’s actual commitment of the wrongful act, correct?

Likewise, if the dog herself did not commit a misdeed, then she should not feel guilty and so should not demonstrate a GL to the owner.

It is also possible that the mere presence of evidence from a misdeed (for example, a dumped-over garbage pail) could become a learned cue that predicts eventual punishment to the dog. In this case, a dog would be expected to show a GL in the presence of the evidence, regardless of whether or not he or she was personally responsible for it. This last study tested both of these factors.

Study 3

Using a similar procedure to those previously described, the researchers created scenarios in which dogs either did or did not eat a forbidden treat in their owner’s absence. They then either kept the evidence present or removed it prior to the owner’s return to the room. Owners were instructed to greet their dogs in a friendly manner and to determine whether or not their dog had misbehaved based only upon their dog’s behavior.

The Results – Owners were unable to accurately determine whether or not their dogs had misbehaved based upon their dog’s greeting behavior, and the dog’s actions did not increase or decrease the inclination to greet the owner showing a GL. A dog’s inclination to demonstrate a GL was also not influenced one way or the other by the presence of evidence.

The second finding suggests that the presence of evidence is not an important (learned) trigger for the GL in dogs. Rather the strongest factor that influences whether or not a dog exhibits a GL upon greeting appears to be the owner’s behavior.

Third and final nail: Neither engaging in a misdeed nor seeing evidence of a misdeed accurately predict whether or not a dog will show a GL.

Take Away Points

These studies tell us that at least some dogs who show signs of appeasement, submission, or fear (a.k.a. the GL) upon greeting their owners will do so regardless of whether or not they misbehaved in their owners’ absence. We also know that an owner’s behavior and use of scolding and reprimands are the most significant predictors of this type of greeting behavior in dogs. These results should be the final death throes of belief in the GL. Good riddance to it!

Now, all that needs to be done is that trainers, behaviorists, and dog professionals everywhere work to educate and encourage all dog owners to please stop doing what the owner is doing in the photo!

Cited References

1. Horowitz A. Disambiguating the “Guilty Look”: Salient Prompts to a Familiar Dog Behavior. Behavioural Processes 2009; 81:447-452.

2. Hecht J, Miklosi A, Gacsi M. Behavioral Assessment and Owner Perceptions of Behaviors Associated with Guilt in Dogs. Applied Animal Behavior Science 2012; 139:134-142.

3. O stojic L, Tkalcic M, Clayton N. Are Owners’ Reports of Their Dogs’ “Guilty Look” Influenced by the Dogs’ Action and Evidence of the Misdeed? Behavioural Processes 2015; 111:97-100.

Linda P. Case, MS, is the owner of AutumnGold Consulting and Dog Training Center in Mahomet, Illinois, where she lives with her four dogs and husband Mike. She is the author of Dog Food Logic and many other books and publications on nutrition for dogs and cats. See her blog at thesciencedog.wordpress.com.