[Updated March 15, 2017]

Recently, we explored the explosion in the numbers and kinds of canine commercial foods aimed at capturing consumers on the basis of their dogs’ age, size, and breed (see “A Special Food for Every Dog?” WDJ June 2002). But as we will see, even “medical” diets seem to have multiplied like rabbits!

Medical diets are the ones formulated for dogs with health problems, from vexing but garden-variety conditions such as itchy skin or digestive issues, to more serious health problems such as cancer or kidney disease. Some of these foods are what we’ll call “veterinary diets” (available only from veterinarians); the rest are over-the-counter (OTC) products, available in any pet supply store.

The number of products available in both types of medical categories has dramatically increased. OTC foods claiming to “promote” healthy coats or “support” digestive function are ubiquitous in pet supply stores and even grocery stores. Hill’s Pet Nutrition was once the only maker of foods that are available only with a veterinarian’s prescription; there are now several major manufacturers offering competing product lines, including Eukanuba, Innovative Veterinary Diets (IVD), Purina, and Waltham.

Vet-Prescribed and OTC Dog Foods: What’s the Difference?

While all of these medical diets claim to benefit dogs with certain health conditions, there are some significant differences between veterinary and OTC products.

Veterinary foods are available only from veterinarians. In theory, a dog would receive a “prescription” for one of the foods following a specific diagnosis, and the vet would monitor the effect the diet had on the dog. If a manufacturer wants to claim that its product can prevent or treat disease, the Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), a branch of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), requires research that proves this. The maker must provide extensive documentation that the food is both safe and efficacious – that it does what it says.

In contrast, OTC food labels are couched in very general terms. They can’t say their products “prevent” or “treat” anything; those are medical claims. Instead, they use vague verbs such as “support” or “promote.” Because they do not make medical claims, the makers of these foods are not required to prove that their products actually do what they say they do.

Another difference is that while the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) sets the standards for OTC pet foods, and the individual state feed control officials regulate the manufacturers in their own states, veterinary diets are solely within the purview of the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine. The labels on veterinary foods must still comply with AAFCO’s general guidelines, but the CVM oversees and enforces the medical claims.

Below, we examine the products – both veterinary and OTC – aimed at each major category of medical conditions. Keep in mind that the differences among foods in each of these categories – especially the products made by the five big veterinary diet makers – are more subtle than the differences we noted between products made for dogs based on age, size, or breed. The parameters for conventional treatment of a particular disease tend to be narrow, necessarily making these diets similar in theory and content.

Vet-Prescribed Kidney Diets

Hill’s founder Mark Morris pioneered the concept of “prescription diets,” as well as Hill’s methodology of naming its products with lowercase letters (so annoying to editors!). Hill’s k/d (kidney diet) was Morris’ first prescription diet, a low-protein, low-phosphorus food he created to save a guide dog named Buddy who was suffering from kidney failure.

Today, there are at least eight different foods promoted for dogs suffering from chronic renal failure. The thing to note here is that these diets are beneficial only to dogs that have already been diagnosed with this condition. There is no proven benefit to feeding such a diet to older dogs that have normal kidney function; these diets do not prevent kidney disease, and are so low in protein that they may actually be detrimental to healthy dogs.

That said, these diets are excellent for managing the symptoms of kidney failure, and at least one study claims that life expectancy is increased in dogs fed such diets. According to representatives from Hill’s, its h/d (heart diet) formula can also be used for chronic renal failure, since it is also relatively low in protein and phosphorus as well as sodium. One competitor claims that Hill’s l/d (liver diet) also falls into this category, though Hill’s does not – l/d is low in protein but not restricted in phosphorus.

Eukanuba makes two kidney formulas, Early Stage (which contains somewhat less protein than its normal foods, at 18 percent as fed), and Advanced Stage (containing 13 percent protein as fed). IVD’s offering in this category is Select Care Modified, which can do double duty for kidney and heart disease. Purina NF (kidNey Failure) is similar to Hill’s k/d, and Purina’s CV (CardioVascular) is similar to Hill’s h/d. Waltham has one kidney formula, Low Phosphorus Moderate Protein, which is referred to in its advertising as “Restricted Protein,” maybe just to confuse us.

There are no OTC foods made to address kidney failure, although some weight loss or senior formulas may contain lower protein than many maintenance foods.

Vet-Prescribed Urinary Tract Diets

While we’re on this tract (sorry!), we should also mention that there are a number of veterinary diets designed to minimize, prevent, dissolve, or otherwise have an effect on the formation of bladder stones. Interestingly, this concept has yet to be realized in the OTC market for dogs, though there are many such diets for cats on your grocery store shelves.

In dogs, stones are usually either struvite or calcium oxalate, though there are a few other more unusual stones such as urate and cystine, and stones may contain combinations of mineral types. This is a case where a vet’s reading of your dog’s test (urinalysis) results would be critical for effective prescribing. Some breeds are prone to one or more types of stones (for example, urate in Dalmatians, struvite and calcium oxalate in Schnauzers). Hill’s makes three types of stone diets: s/d (intended to dissolve struvite stones by extreme acidification of the urine), c/d (also acidifying but intended for prevention), and u/d (for urate and cystine).

IVD’s Select Care provides Control (for struvite), Modified (for calcium oxalate), and Vegetarian (for the “metabolic” stones, urate and cystine). Oddly, Purina only makes a struvite diet (UR) only for cats, and Waltham has only one struvite diet, S/O Lower Urinary Tract. Perhaps Hill’s is so entrenched in this market that its main competitors don’t think it’s worth trying to steal its market share.

Vet-Prescribed Cardiac Diets

Once again, Hill’s was the early entry in this field with its h/d. Hill’s also claims cardiac benefits for its k/d and g/d (geriatric diet). Eukanuba’s contribution to this category is its Advanced Stage kidney diet; IVD’s offering is its Select Care Modified kidney diet. Purina does have its CV formula, but allows that its NF formula can also be used. Waltham has just come out with an “Early Cardiac Support” diet.

The main feature of cardiac diets is low sodium – even though there has never been any real evidence that sodium has any effect on hypertension or heart disease in dogs. Even for human health, the latest research shows that unless you are sensitive to sodium, salt may not raise blood pressure – and salt sensitivity is rare, even among individuals with high blood pressure.

However, manufacturers are catching on to the connection, long known in felines, between taurine, carnitine, and heart disease. CV, h/d, and Early Cardiac Support all contain added taurine and carnitine; the levels of taurine and carnitine in CV are somewhat higher than in h/d. Early Cardiac Support is a rice and fish-based food using menhaden (a kind of herring) meal, which is a good source of Omega 3 fatty acids. Foods with more carnitine and taurine may be better for a dog with heart problems, and the antioxidant and other health-promoting properties of Omega 3 fatty acids may also be helpful.

We’ve not yet seen any OTC entries in the cardiac care category.

Joint Health Diets for Dogs

Numerous studies have shown glucosamine and chondroitin to be beneficial supplements for people with arthritis for relieving joint pain and improving mobility. Numerous OTC adult and senior dog foods, as well as a few large breed puppy foods, now include glucosamine and chondroitin with the advertised purpose of promoting joint health, implying (but not claiming) that they can prevent arthritis.

In the veterinary diet arena, Eukanuba has introduced Senior Plus, which includes glucosamine and chondroitin as well as added antioxidants, Omega 3 and 6 fatty acids, carnitine, and chromium.

Waltham also has a veterinary diet (Joint Support) which contains perna mussel powder from the New Zealand green-lipped mussel, Perna canaliculus. This shellfish contains large amounts of glycosaminoglycans similar to glucosamine and chondroitin as well as the Omega 3 fatty acids EPA and DHA. At least one study showed dramatic improvement in arthritis pain in people taking perna mussel; however, there is no evidence that it will prevent arthritis.

While glucosamine and chondroitin (and probably green-lipped mussels) appear to be safe in the numerous studies examining them, few dog foods contain them at an amount that could reasonably be expected to have any effect at all, and few makers of these foods even tell you how much is present in their products.

Also, believe it or not, inclusion of these ingredients has never been approved for use in animals and is currently considered illegal by the FDA and AAFCO, although only a few states have attempted to stop the sale of foods containing them. A petition was recently introduced to AAFCO to approve a definition for glucosamine, but no action has been taken as yet.

The most significant problem with these “joint support” foods is that there has never been any scientific evidence that supplemental glucosamine or chondroitin will prevent arthritis. Virtually all studies of these ingredients were done in humans who already had arthritis. Also, we are not aware of any evidence demonstrating that these supplements arrive in the dog’s bowl (or in her tummy, let alone her joints) in a form or at a level that has been proven to be beneficial to either prevent or treat arthritis.

Oral/Dental Health Dog Foods

Hill’s Science Diet and Nutro are currently the primary makers of OTC dental care formulas. Hill’s actually makes another, more convincingly proven dental formula called “t/d,” which is available only through veterinarians. Hill’s claims that its OTC “oral care” formula will actually remove tartar from the teeth.

If the lack of visible tartar on the teeth gives you a false sense of security to the point of not brushing your dog’s teeth, or not visiting a veterinarian at least annually, these foods may ultimately do more harm than good. Other scientific research on the subject suggests that some “oral health” dog foods merely produce less tartar than other dry foods, certainly not zero tartar. In one study comparing an unspecified oral health diet to regular dog food plus a special chew, dogs on the oral health diet had more tartar, and worse, lost weight and condition.

Vet-Prescribed Diabetes Diets

Who knew so many dogs were diabetic? There must be a lot of them, because there are a lot of these diets.

The mainstay of diabetes treatment in pets has always been a high-fiber diet, which theoretically slows digestion and maintains a steadier blood glucose level. Recent research in cats has dramatically reversed this thinking, with high-protein, high-fat, very low-carbohydrate/fiber diets such as Purina DM or even canned kitten food providing the best results in terms of reduced insulin levels, normalization of weight, and symptom control. Canine research has yet to catch on to this concept. Most diets making a claim for diabetes management are also used for weight loss.

Eukanuba has taken the boldest step into this arena with its frankly named Glucose Control diet, with 25 percent protein, 5.5 percent fat, and 5 percent fiber as fed. Its Restricted Calorie diet (generally considered a weight reduction diet at 22 percent protein, 5 percent fat, and 7.5 percent fiber as fed) also qualifies.

Hill’s makes two diets that take the prize for fiber: r/d (reducing diet) at 20 percent protein, 5 percent fat, and 26 percent fiber, and w/d (weight diet) with 15 percent protein, 6 percent fat, and 20 percent fiber, as fed, on the theory that if a little is good, a lot must be really good – but it doesn’t seem to leave much room for actual food!

IVD’s Hifactor comes in at 23 percent protein, 10 percent fat, and 13 percent fiber. Purina makes DCO (Diabetic/COlitis diet), which comes in at 23 percent protein, 10 percent fat, and 10 percent fiber, and OM (Obesity Management) diet at 26 percent protein, 4 percent fat, and 16 percent fiber as fed. Waltham offers its High Fiber with 18 percent protein, 6 percent fat, and 5 percent fiber as fed.

We’re not aware of any OTC diets for diabetic dogs.

Veterinary Foods for Dog Obesity

We discussed OTC “light” foods in “A Special Food for Every Dog?” (June 2002). But the list of veterinary diets for treating obesity is almost the same as the diabetes diets. This should come as no surprise; most dogs who get diabetes are overweight, and the treatment for both is traditionally the same.

These veterinary foods all provide between 200-300 calories per cup of kibble, compared to 300-400 for most maintenance-type foods (including most other veterinary diets). Eukanuba’s Restricted Calorie contains 238 calories per cup, and its Glucose Control has 253 calories per cup, as fed. Hill’s r/d contains 220 calories, and w/d 243 calories, per cup as fed. IVD’s Hifactor contains 230 calories per cup.

Waltham has two special entries in this category in addition to its High Fiber (227 calories per cup as fed): Low Fat (19 percent protein, 4 percent fat, 2.5 percent fiber, and 264 calories per cup as fed) and Calorie Control (27 percent protein, 4.5 percent fat, 3.5 percent fiber, and 212 calories per cup as fed – the lowest of all).

Vet-Prescribed Geriatric Dog Food

Again, we discussed OTC “senior” foods in the June 2002 issue. The OTC market in mature and senior foods is booming as our dog population becomes larger and older over time. In general, these foods are lower in fat and calories than maintenance foods, but you have to watch the labels, as some makers seem to be formulating their senior dog foods for skinny old dogs, not fat ones.

Veterinary diets for obese old dogs include Eukanuba’s Restricted Calorie and Glucose Control diets; Hill’s w/d also falls into this category. IVD has Select Care Mature (289 calories per cup as fed).

Hill’s g/d (Geriatric Diet) contains 358 calories per cup as fed, making it a better choice for skinny old dogs. This food is specifically intended for dogs “at risk” for heart and kidney disease.

Dog Foods for Allergies and Gastrointestinal Disease

This is where things really get complicated! If we look at all the veterinary diets intended to treat all types of allergies including Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), we find 16 basic diets, with several additional variations on the theme. Some are promoted to treat allergic skin disease, while others address food intolerances, true food allergies, and a variety of GI ailments, but there is a great deal of crossover in these categories so we will consider them all in this section.

Food intolerances and allergies in dogs tend to manifest in two primary ways: skin disease and gastrointestinal disease. Allergic skin disease (such as rashes, itchiness, ear infections, and lick granulomas) is most commonly caused by inhalant allergens (dust, pollen, etc.), but dogs can be truly food-allergic. Diarrhea and other GI signs can be caused by a food allergy, but are more often the result of a food intolerance, rather than a real immunologic reaction to a food component, which is the hallmark of a food allergy. Let’s consider some of the more distinct syndromes in this category, starting with the gastrointestinal diseases.

• Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Not everyone agrees that IBD is a food allergy, but it is certain that diet can play a large role in its management. Symptoms of IBD include vomiting and diarrhea, though not necessarily both, and not necessarily at the same time.

Two dog foods fall more into the IBD management category than the others, and they are also touted for their ability to treat pancreatitis, colitis, diarrhea, constipation, and gastrointestinal disease in general. These are Eukanuba Low Residue, and Purina EN (ENteric, meaning intestinal). Low Residue contains moderate levels of soluble fiber, is overall low in fat but with a “balanced” Omega 3 to Omega 6 fatty acid ratio, and is highly digestible. EN is low in fiber and fat, and provides extra medium-chain triglycerides, all of which theoretically make it easier to digest. IVD’s Select Care Neutral, also a relatively “hypoallergenic” diet, can be used as well.

• Pancreatic disease. Pancreatitis in dogs is correlated with dietary fat, so the IBD diets may be particularly well-suited to treating that condition. Hill’s i/d (intestinal diet) is considered a good diet for pancreatitis, and is often the first choice of veterinarians for just about any digestive problem. Failure of the pancreas to produce sufficient enzymes for digestion can result in incomplete digestion and assimilation of food. IVD’s Select Care Neutral, Sensitive, and Vegetarian formulas all contain digestive enzymes that may be helpful. Purina EN is also recommended for these problems due to its low fiber and high digestibility. Diabetes is sometimes a consequence of primary pancreatic disease, so the diabetes diets might also be appropriate.

• Diarrhea or constipation. Since these are kind of “opposite” conditions, you might expect that diets for these two conditions would be completely different. However, the use of fiber to moderate gastrointestinal motility – slowing it down in the case of diarrhea, or speeding it up in constipation – creates the ability to use some of the same diets for both. Therefore, most of the weight management diets could be used here.

Eukanuba’s Nutritional Intestinal Formula Low-Residue can be used for both of these as well as other problems such as flatulence, vomiting, and colitis (inflammation of the colon). Hill’s i/d is frequently used for these conditions as well. IVD’s Select Care Neutral is indicated for chronic GI diseases, small bowel diarrhea (increased volume, frequency, and water content of stool), and IBD, while its Select Care Sensitive is more suited for acute GI diseases – viral or bacterial diarrhea, perhaps, or recovery from an episode of “garbage gut,” where a dog ate something he shouldn’t have eaten. Purina EN and Waltham High Fiber also cover these conditions.

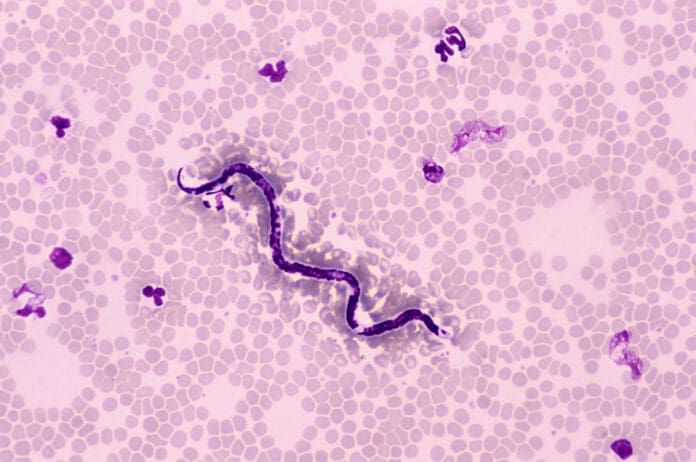

• Colitis. Inflammation of the large intestine (colon) can result from many causes, including stress, parasites, allergies, or cancer. While this can lead to constipation, it is more often associated with diarrhea. The dog needs to go more frequently, although the amount of stool is typically small, and there may be mucus or blood present on or in the stool. Parasitic colitis, of course, must be treated with an appropriate dewormer.

But for dietary or stress colitis, high fiber is, once again, the most common treatment. (In a few cases, excessive dietary fiber may actually irritate the colon, worsening the problem.) Eukanuba Low-Residue, Restricted Calorie, and Glucose Control, Hill’s i/d and w/d, IVD’s Hifactor, Purina’s DCO and OM, and Waltham’s Calorie Control and High Fiber might all be appropriate for dogs with colitis.

• Skin reactions. The primary theory behind diets for allergic skin disease is that allergies develop to items that the dog has been exposed to for a long time. By feeding ingredients the dog has not had before, the immune system is no longer challenged by the original allergens, and things should calm down. This was the origin of the “lamb and rice” diets. However, so many foods now contain lamb and rice that these ingredients have become less useful for treatment (though rice still seems to be fairly benign for most dogs). Manufacturers have had to scramble to find other “novel” or “alternative” protein and carbohydrate sources.

This is why we now have Eukanuba’s Nutritional Skin & Coat Formulas (Fish & Potatoes, Kangaroo & Oats), Hill’s d/d (Lamb & Rice, Rice & Duck, Rice & Egg, Rice & Salmon, and Whitefish & Rice), IVD’s Select Care Vegetarian and IVD Limited Ingredient Diets (Rabbit, Venison, Whitefish, and Duck with Potatoes or Green Peas), and Purina’s LA (Limited Antigen) diet (rice, salmon, and trout).

A slightly different theory about food allergies has spawned Hill’s z/d and z/d ULTRA, and Purina’s HA (Hypo-Allergenic) diets. The idea is that the immune system reacts only to large proteins (such as those found in chicken, corn, or beef) that are absorbed intact. If you chop up all the proteins into little tiny pieces before the dog eats them, they will essentially “fly under the radar” of the immune system and not provoke an allergic reaction. This is a great theory, and allows the use of ordinary ingredients (chicken, in the case of z/d) as long as they go through a special process that breaks down the proteins. The dog can fully utilize the amino acids contained in these proteins, so the food still provides complete nutrition. Purina HA is actually a vegetarian food using soy protein instead of meat.

The only problem with this theory is that it doesn’t always work. There have been cases where an animal has become allergic to z/d or a similar diet. It’s uncommon, but it lends credence to the idea that it’s wise to change foods periodically, so the immune system is not bombarded with the same ingredients year after year. Your dog may be far less likely to develop a food allergy in the first place if you follow this advice.

There are a number of OTC dog foods that attempt to mimic some of these veterinary diets – without making specific medical claims. Hill’s makes “Sensitive Skin” and “Sensitive Stomach” formulas. Precise also makes a “food allergy” type formula, “Sensicare,” which also claims to protect the skin. Hill’s skin formula contains egg protein, plus extra Omega 3 and 6 fatty acids and antioxidants compared to its regular adult maintenance food. It’s certainly true that these ingredients will help keep the skin and coat in better condition.

Oddly enough, Hill’s “Sensitive Stomach” food has an identical list of ingredients and identical guaranteed analysis. However, according to a Hill’s customer service representative, the products have different formulations, which is possible if the proportions of ingredients are different.

Both foods claim relatively (compared to other brands) high levels of the antioxidant vitamins C and E. Those other brands must not have much vitamin C, since a dog would have to eat a pound of Hill’s kibble just to get 100 mg of it! The vitamin E content is higher, since it is also contained in the preservative system. Most of Hill’s veterinary diets are preserved with artificial preservatives BHA, BHT, and propyl gallate, so its OTC foods in this category may be a better choice on that criterion alone.

Growth and Recovery Dog Foods

There are several veterinary diets available for animals who are just plain sick, or who are recovering from illness, injury, or surgery. These high-fat, high-protein formulations are available only in cans. Hill’s a/d is a standard for animals who need a lot of energy packed into a small amount of food. It is also extremely palatable and easy to digest; its smooth, pudding-like texture makes it perfect to force-feed by syringe, or to administer through an implanted feeding tube. IVD’s SC Development and Euka-nuba’s Maximum Calorie have somewhat similar characteristics and indications.

Hill’s p/d (pediatric diet) is also a high-calorie, easily digested food, designed for puppies but suitable for older dogs who need big-time nutrition fast. It comes in both canned and dry versions.

Unique Formula Dog Foods

Hill’s Pet Nutrition, long the leader in veterinary diet innovations, has three unique formulas that are worthy of mention, and have not (yet) been imitated.

Hill’s l/d (liver diet) is designed for animals with liver disease, such as canine hepatitis. It features low copper and can be used in dogs (primarily Bedlington Terriers) with metabolic copper storage disease. It contains a mix of amino acids thought to maximize liver function, and high levels of antioxidants to protect the liver.

The company’s n/d (neoplasia diet) is based on research conducted at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences on canine cancer and diet. It seems that cancer cells are particularly fond of carbohydrates. Dry dog foods generally are composed of half or more carbohydrates, and even most canned dog foods contain a fair amount of starch. Feeding canine cancer patients lots of carbohydrate-based foods may well be feeding their cancers.

To address this, Hill’s developed n/d, a high-protein, very high-fat diet with minimal carbs. Cancer patients benefit from extra protein and fat, which can help prevent muscle wasting and theft of protein and fat by the tumor. The n/d formula also features very high levels of Omega 3 fatty acids, which have anti-cancer properties, and high levels of the amino acid arginine, which aids immune function. Studies show that, even after the tumor has been surgically removed or killed by chemotherapy or radiation, cancer-induced alterations in metabolism persist, so n/d should be fed “forever” to dogs who have had cancer.

Hill’s newest entry in the field of veterinary diets is b/d (brain diet). According to Hill’s promotional literature, b/d has been shown to “improve alertness, increase attentiveness to problem-solving tasks, and improve enthusiasm, so they feel younger.” Just exactly how they asked the dogs how old they felt is not disclosed, but that’s the claim. This food contains high levels of antioxidants. Oxygen free radicals are thought to be the major contributor to human aging, so antioxidants should reduce the signs of aging. This appears to be the mechanism of b/d. This food also contains some nice veggies like spinach and carrots, to appeal to those looking for a more “natural” food than is usually associated with Hill’s.

Conclusions

While Hill’s is probably not all that thrilled with sharing a market that was once Hill’s alone, the competition in both veterinary and OTC diets is good news for dogs whose medical conditions improve with nutritional adjustments. If your veterinarian prescribes a certain diet for your dog, but your dog does not like the food or doesn’t do well on it, or his condition doesn’t improve as much or as rapidly as expected, try one of the other formulas in the same category.

Remember that OTC foods cannot be expected to produce the same results as veterinary diets; they are not as rigorously researched and are allowed onto the market without proof that they work like their labels say they do.

And finally, keep in mind that medical diets are formulated to address specific medical concerns, not to maintain long-term health in dogs of all ages, sizes, and breeds. These foods rarely meet WDJ’s normal selection criteria for top-quality foods (see “Choose the Best Dry Food,” WDJ January 2016). As a rule, the smaller, independent food makers who produce the sorts of foods we regard as supreme in quality do not offer diets for medical conditions.

Jean Hofve, DVM, of Englewood, Colorado, is a regular contributor to WDJ.