Imagine living in a world where you are surrounded and controlled by creatures who are 10, 20, even 30 times your size. Now imagine that from time to time, without warning, one of those creatures suddenly reaches down, snatches you off your feet and lifts you up into the air. Now you know how many of our dogs feel – especially our smaller dogs – and why you need to rethink if (and how) you should pick up your dog.

I’ve had a rash of clients recently whose dogs were objecting to being picked up. The dogs’ feelings about being lifted have ranged from avoidance, tense body language, growls, snarls, and snaps, all the way to serious bites and visits to the emergency clinic for the unfortunate humans who chose to ignore the earlier warning signs. (To learn more about early warning signs that dogs may give when they are uncomfortable, see “Dog Growling Is a Good Thing,” WDJ December 2016, and “Learn to Read Your Dog’s Body Signals,” August 2011.)

Suffering the indignity of being unceremoniously grabbed off the ground is primarily an affliction of small dogs, but there are a surprising number of medium-to-large dogs whose humans also feel compelled to lift and carry them. Certainly, there are times when a dog needs to be carried – for example, when she’s injured or can’t otherwise negotiate the terrain on her own for some reason. In anticipation of those times, it’s worth taking the time to learn how to do it properly – and to help your dog be happy about the process.

Other than in times of necessity due to some calamity, with the exception of those dogs who actually do enjoy being carried, it’s best to minimize the times you sweep your dog off her feet. If you’re not sure how your dog feels about being picked up, ask an experienced force-free professional to help you interpret her body language. Does she truly enjoy it, or is she just tolerating the snatch and lift?

PAIN MAY BE THE ROOT CAUSE

Although we suggest not lifting most dogs unless absolutely necessary, there may be occasions when your dog must be lifted. Those occasions will go a lot smoother if you have invested the time in helping your dog be comfortable about being picked up.

The most important part of your dog-pick-up technique is to make sure you’re not causing your dog any discomfort – physical or emotional. Let’s look at the physical part first:

First, never lift a dog by their armpits. This is the best way to give your dog a negative association with being picked up – it hurts!

If your dog growls or tries to avoid being picked up, she may very well be experiencing pain during the lift. At her next check-up, ask your veterinarian to do a thorough physical examination to determination if a physical problem could be causing her reluctance to be picked up. If she’s hurting from arthritis, a strain, sprain, or any number of other conditions that can cause pain, you are guaranteed to give her a negative association if you try to pick her up.

While arthritis or a misalignment in the spine are probably the most common causes of pain in dogs who are picked up, even something like an ear infection or imbedded foxtail can cause her to be wary of the close contact required when being lifted. Treat or manage any pain-causing conditions before starting new lifting procedures. And be aware that even a painful event that happened in the past can sour your dog on the idea of being lifted; she may anticipate that the action might hurt her badly again.

BETTER WAYS TO LIFT YOUR LOVED ONES

The following methods for picking up your dog are less likely to cause pain and will make your dog more comfortable when being lifted:

Photo Credit: Lifeontheside/

Dreasmstime.com

* The Chest Cradle. To lift a medium or large dog comfortably, you want to cradle her in your arms – with one arm around the front of the chest and the other around her hind legs, below her tail and above her hocks, mid-thigh. Press the dog’s body against your chest and lift, making sure the entire dog is well-supported so she feels safe. Be sure to bend your knees and rise straight up (as much as possible); the more you bend at the waist the less secure your dog will feel.

A second option is to lift with one arm around the front of the chest and one around the dog’s waist – but this has more potential for causing discomfort, because the dog’s weight is resting on your arm and pressing on her underbelly.

* The Ribcage Lift. You can use the above-described Chest Cradle to pick up your small dog, too. The Ribcage lift is another acceptable alternative. For this one, place one hand under the ribcage just behind your dog’s front legs and cup that hand around the elbow of her front leg on the far side. Put your other arm over the top of and around your dog’s body just in front of the hind legs, with your hand around the entire ribcage. As you lift, hold her close and press your elbow against her hip to support her body securely against yours.

* Lift Alternatives. There are alternatives to lifting your dog. I encourage you to use these as much as possible.

• You can invite her to jump up on your bed, the sofa, or into your car rather than lifting her in.

• If your dog can’t jump for some reason (or can’t jump high enough), use a ramp!

• If your small dog prefers not to be lifted, you can invite her to happily go into her crate (or jump in a laundry basket) and carry her that way.

• Another option for your small dog is to teach her to jump into your lap while you’re sitting – and then stand up while holding her, well-supported against your chest.

• If your dog is athletic, you can teach her to leap into your arms. Sunny, our 30-pound Pomeranian/American Eskimo Dog-mix, delights in jumping into my arms from the ground. (Of course that wouldn’t work if he were injured, so I still want him to be happy about being lifted when necessary.)

• Some small dogs may be more comfortable in one of the various front or backpacks designed for canine carrying, rather than being held in your arms.

• Many veterinary exam rooms have tables that can be lowered and raised. Ask your vet if she can lower the table and invite your dog to hop up on her own, rather than lifting her up.

• Similarly, a lift tailgate on a truck can be used the same way.

PICK UP TRICKS

Then there’s the training part. You can help your dog be happy about being lifted by giving her a new, positive association with the procedure and allowing her to have a choice in the process.

We’ll put our reliable old friends counter-conditioning and desensitization to good use here. (Technically, if your dog has no prior association with being picked up, you are conditioning – that is, creating an association – rather than counter-conditioning, which is changing an already existing association, usually from negative to positive.)

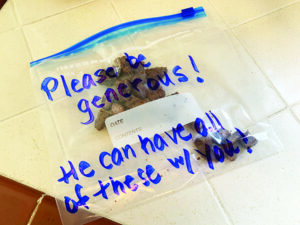

Break the picking-up process into small increments and get your dog happy at each step by pairing it with high-value treats (chicken is my favorite – low fat, low calorie, and high value for most dogs).

Start by reaching toward your dog, then feed a treat while your reaching hand is still offered. Repeat this step until she eagerly looks for chicken each time you reach. The next step will be to touch her and feed her a bit of chicken.

Gradually add steps that move you toward picking her up, making sure she is happy (not just tolerant) at each step before proceeding to the next.

When you are ready to actually begin lifting, add a cue. “Up” may come to mind, but if you use “up” to mean jump up on something (like I do) then you need to use something else. I use “Lift” for this, but you can use any cue you want as long as it’s unique to this behavior.

Say your “Lift!” cue and put very gentle upward pressure on your dog’s body, regardless of which lift procedure you have elected to use. Then feed a chicken treat (you are still doing counter-conditioning). As you continue, look for signs that your dog is participating in the process – perhaps moving into your hands when you lower them for the lift – and eventually boosting herself up when you give the “Lift” cue.

When she regularly offers those moves, you have established a cooperative care procedure; she is a willing partner in the lift. Congratulations! This is our goal with all the things we do with our dogs; we are always looking for signs that they are happy participants in the activities we ask them to do with us.

Of course, now you have an obligation to her. When you say “Lift!” watch for her to offer her signal that she is ready and willing to be lifted. When she signals, proceed with the lift. If she doesn’t offer the signal, she is telling you she’s not ready or not comfortable. Don’t pick her up. Reposition and try again.

If she repeatedly declines to be lifted, look for an alternative option – one of the several described above. Only if it’s an absolute emergency will you pick her up without her approval signal. For example, if she’s injured and needs to be rushed to the vet, the flood waters are quickly rising, or the wildfire is rapidly advancing on your home and you have to evacuate now. In that case, by all means pick her up – gently and carefully – and make a mental note to go back to refresh her pick-up training when there are no pressing emergencies.

Note: If your dog is seriously injured, I recommend muzzling her before picking her up. Pain can cause even the gentlest dog in the word to bite if the injury is jostled. If you don’t have a muzzle, a leash may do. Animal-control officers routinely leash-muzzle the injured dogs they pick up, by wrapping the leash snugly around the dog’s muzzle and holding it tightly while lifting the dog.

TRAIN ANY METHOD

Photo Credit: AleksandrZyablitskiy/

Dreamstime.com

If you plan to use alternatives to lifting, you’ll need to train those also. Your dog needs to already be very happy about her crate before you use it to physically move her, and you’ll still want to do lots of crate games with her, without moving the crate so that any trepidation caused by the moving crate is greatly outweighed by all the fun stuff.

Teach her the fun game of jumping into a laundry basket and play the game with her regularly, so the fun far outweighs any stress that might be caused by carrying her in it. If you plan to use a ramp or a lift board, introduce her to it and take the time (with treats, of course) to show her how to use it. If you want to use a pack or carrier, teach your dog to happily jump in on her own, so you don’t have to lift her to put her in it.

If your vet uses a table lift, ask if you can do happy vet visits where you introduce her to the table without it being part of an intrusive exam, and continue to occasionally drop by (during the clinic’s slow times) so you can play more fun table games with your dog. We recommend happy vet visits anyway, so this is just one more thing to include in your vet-visit repertoire. (See “Fear Free Veterinary Care,” August 2019.)

CARRIED AWAY

Compared to many of the behavior challenges I see with my clients’ dogs, the lifting problem is a relatively easy fix. The inappropriate dog-lifting I have seen with recent clients has been due solely to a lack of awareness on the humans’ part. I gently suggest to them that just because they can pick up their dogs doesn’t mean they should. Once educated about proper dog-lifting, each of them has jumped on board with protocols to minimize the need to lift and to help their dogs be more comfortable with being picked up if/when necessary.