by Randy Kidd, DVM, PhD Given the incredibly intricate and complex series of events that need to occur to produce living puppies, it is almost miraculous that any pups are ever born, but they are. And, more often than not, nature doesn’t seem to have many problems with the process. Following are some explanations for what goes on during and immediately after pregnancy. The length of pregnancy in dogs is a remarkably consistent 64 to 66 days – if we measure from the surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) that triggers ovulation. However, most pregnancies are not monitored by measuring blood hormonal levels, and if we start counting the days from a single mating, pregnancy may vary from 56 to 72 days – 63 days is the traditionally accepted norm.

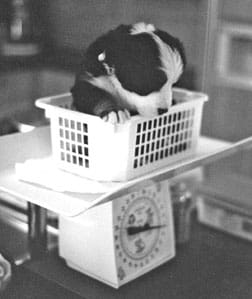

Pregnancy can be diagnosed by manual palpation between days 20 and 35, but this method relies on the skill and experience of the one doing the palpation and his or her ability to discern discrete uterine enlargements (fetuses) from other lumps that occur in the abdominal cavity – the bladder, kidneys, and fecal accumulations in the colon, for example. After day 25, ultrasound is effective. Your veterinarian can take a blood sample and run an in-office test (serum relaxin assay) after day 30 to confirm pregnancy. Relaxin is a hormone that facilitates the birth process by causing a softening and lengthening of the cervix and the pubic symphysis (the area where the pubic bones come together). Relaxin also inhibits contractions of the uterus and may play a role in the timing of delivery. Toward the end of pregnancy the female will begin to produce milk (usually at about day 45), and many will begin to make a “nest.” During the 24 hours just prior to parturition (also known as whelping), a female’s progesterone level usually falls below the level required to support pregnancy (2 ng/ml), and this drop is responsible for a rectal temperature drop, to a mean of 98.8°F (range 98.1-100.0°F). Many breeders use this fall in temperature to predict whelping. Environment’s importance during pregnancy There are at least three outside variables that influence the intended outcome of healthy pups – variables that the bitch’s caretaker can influence: nutrition, nurturing, and paying attention to the healthy history of the parents. Nutrition is especially important. There are many studies that demonstrate the necessity of adequate basic nutrition during pregnancy, and studies that prove that inadequate nutrition results in smaller, less healthy offspring who have a propensity for developing a variety of diseases later in life. During the first four weeks of pregnancy, the fetuses don’t have a lot of weight gain; the mother’s caloric intake should be monitored to keep her from gaining weight during early pregnancy. The Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) recommends a minimum of 22 percent protein and 8 percent fat in the diets of pregnant and lactating females, especially during the last half of pregnancy. (Comparable figures for the “adult maintenance” diet are 18 percent protein and 5 percent fat.) According to AAFCO, pregnant females have the same needs for vitamins and minerals that adult dogs require for maintenance. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, implicit in any list of nutrient requirements is the absolute need to balance the nutrients. This is the biggest problem I see in the homemade diets used by my clients. For one reason or the other – usually it is something like, “Well, he just doesn’t like the veggies!” – folks will eliminate an important component of the diet, and by doing so, their home-prepared diet is no longer adequately balanced. Scientifically backed evidence for the importance of nurturing during pregnancy is a bit more difficult to come by, but we do know that there are some negative factors that adversely affect the health of the dam’s offspring. We know, for example, that excess stress (or the use of therapeutic corticosteroids) has a negative effect on the uterine environment; too much stress during development can produce puppies that are difficult to socialize, and too heavy a load of corticosteroids can actually cause abortion. We also know that moderate exercise during pregnancy is good for the development of healthy neonates. And, for the good of the neonates (and the bitch) it just makes sense that we try to provide a calm, loving, and healthy environment during the entire development period of the puppies. Every bit as interesting, from the holistic standpoint, is that recent studies have proven the importance of maintaining optimal health in the dam. It has been shown that a number of disease states can be transferred directly from the dam (or from several generations back), without being genetically transferred. “Prenatal programming” has been shown to occur in a variety of animals, including humans, and it involves the passing on of several diseases. During fetal development, there are critical periods of vulnerability to “suboptimal” conditions, and if the bitch is living under one of these conditions, the likelihood of passing on disease to her offspring is increased. But even more interestingly, the likelihood of problems being passed on to future generations – grand-puppies, great-grand-puppies, etc. – may also be enhanced. Conditions in the dam that result in proven problems for future generations include obesity or malnourishment, excess stress (or exposure to corticosteroids), diabetes, and asthma. It has recently been shown (in humans) that exposure to secondhand smoke may create an added propensity for asthma in the grandkids of the smoker – whether or not they, or their mothers, were smokers themselves. This is ongoing and fascinating research, and it lends credibility to the folks who want to raise puppies naturally, for the sake of many future generations. It’s my guess that we’ll continue to find connections to the health of the dam during pregnancy and the health of many future generations of her puppies. This puts me in mind of the Native American understanding that we need to be concerned about seven generations back and seven generations forward. Labor and delivery During the 6 to 24 hours before birth of the first pup, behavior changes in the bitch may include becoming reclusive, intermittently digging and nesting, panting and shivering, refusing to eat, and/or vomiting. Her vaginal discharge is clear and watery. This phase of normal labor, termed Stage I, is characterized by muscular contractions of the uterus that increase in frequency and strength, and dilation of the cervix. Stage II labor is marked by visible abdominal contractions that reinforce the efforts of the uterus in delivering the pups. Puppies may be born one at a time with a period of rest between each puppy, or several may be born relatively quickly. Pups may be delivered within intact membranes or attached to ruptured membranes. Membranes and placenta are typically eaten by the bitch; vomiting of placental material is common. We once thought that it was important for the bitch to eat her placenta, a rich source of nutrients and a source of the hormone oxytocin, which is necessary to help expel the placentas and to instigate milk flow. Later we learned that oxytocin is destroyed in the stomach, and most of the stimulation for oxytocin release comes from nursing puppies. Overly aggressive or overly concerned mothers may puncture the abdominal wall while attempting to chew through the umbilical cord. Calming flower essences or homeopathic remedies may be helpful here. Severed umbilical cords can be painted with tincture of iodine to help prevent infection. Vaginal discharge during active labor can be clear to hemorrhagic (bloody), or green (uteroverdin or biliverdin is a green pigment that comes from the breakdown of hemoglobin in the blood of the placenta). The interval between puppies (whether singletons or several-in-a-row) is generally less than 30 minutes, but it can vary from 15 minutes to several hours. Typically the bitch will continue to nest between deliveries and may nurse and groom puppies intermittently. Panting and trembling are common, and most laboring bitches refuse food. A litter of 6 to 8 pups can require 4 to 18 hours or more; however, a normal and healthy delivery is typically associated with shorter total delivery time and shorter intervals between puppies. Uterine inertia is treated by administering oxytocin and/or calcium-containing fluids; alternately homeopathic or herbal remedies or acupuncture treatments may be used to hasten a slow delivery. During Stage III labor, the remaining placentas are passed. Most bitches vacillate between Stage II and III until the delivery is complete – that is, puppies and placentas are usually delivered alternately, with no set pattern of delivery. Preventing problems Encourage your pregnant female to deliver in a familiar area where she will not be disturbed. Unfamiliar surroundings or strangers may impede delivery, interfere with milk letdown, or adversely affect her maternal instincts. This is especially true with young or primiparous animals (bearing or having borne but one litter). A nervous dam may ignore the neonates or give them excess attention. A dam’s apprehension or nervousness may subside in a few hours, but in the meantime the pups must receive colostrum and be kept warm. It is normal for a female to have a reddish-brown to black odorless discharge (called lochia) for a few days to several weeks after giving birth. Some folks may want to have their vet palpate or X-ray the female to ensure that all pups have been delivered. The neonates should be weighed accurately (cooking or postal scales that weigh in ounces are effective) as soon as they are dry and then daily for the first week. Any weight loss after the first 24 hours could indicate a serious problem – supplemental feeding, assisting the bitch with nursing, or evaluation for possible infection or other problems may be indicated. Although times may vary, obvious mammary development usually occurs by day 45 of pregnancy, and obvious milk secretion normally begins at or after parturition. Suckling induces the release of hormones necessary for inducing lactation, including oxytocin and prolactin. Lactation lasts about six weeks, with the dam encouraging weaning beginning at about week four or five. Producing milk increases the bitch’s caloric needs three to four times. During the last few weeks of lactation, she may also need calcium supplementation, which can be provided with cottage cheese or yogurt or a balanced vitamin/mineral supplement.

Colostrum is the milk secreted during the first few hours after birth. It is nutrient-rich, and contains whatever immunoglobulins the bitch is carrying at the time. It is thus the source of the puppies’ immunity to infectious disease for the first several weeks of life. For this reason, it is very important to insure that all pups receive an initial feeding of colostrum within a few hours after birth. Also, the production of colostrum may last for a few days, but the pup’s ability to absorb it may only be hours long. Feedings will begin at every few hours, throughout the day and night, and gradually decrease in frequency. By the third week, pups should be introduced to a supplemental food source. If they are going to be fed commercial food, their first “mash” should be a mixture of milk replacer, puppy food, and water, blended into the consistency of human infant cereal. In the same time frame, people who feed their dogs a home-prepared diet will start offering the pups raw, meaty bones to lick and chew. (See “Raw-Fed Puppies,” WDJ December 2003.) Problems of pregnancy, labor, and lactation The most important cause of abortion in dogs is brucellosis, which has been discussed in past installments. Other causes of abortion run the gamut and include a variety of infectious agents, an improper uterine environment (inadequate nutritional level, for example), and trauma. False pregnancy (pseudopregnancy, pseudocyesis) is a fairly common occurrence in dogs, making intact and even some spayed females look and act like they are pregnant when they are not. These females may exhibit mammary development and even produce milk, and may demonstrate “mothering” behaviors such as nesting and treating toys as if they were living pups. Most vets recommend no treatment because the condition usually resolves itself in one to three weeks; the only drug currently approved for treatment of false pregnancy (the progestin, megestrol acetate) may cause pyometra. If the mammary glands seem painful, alternating cold and warm compresses may alleviate the discomfort. For the overly anxious bitch, consider herbal tranquilizers, homeopathic remedies, and/or calming flower essences. Dystocia is the term used to describe abnormal labor or parturition. It can be caused by uterine inertia, pelvic canal abnormalities, oversized or poorly aligned fetuses, or any combination of these. Uterine inertia that develops after the delivery of one or more neonates (secondary inertia) is the most common cause of dystocia. Treatments include calcium and oxytocin. Note that it is important that the timing and dosage of these drugs is critical to their success. Alternative treatments include homeopathic remedies and acupuncture. Neonatal deaths are not uncommon for puppies kept under even the most stringent levels of care; reported average neonatal mortalities range from 15 to 25 percent. The most common metabolic disease of the postpartum bitch is eclampsia; common inflammatory diseases include metritis (often from a retained placenta or fetus) and mastitis. Eclampsia (also known as puerperal hypocalcemia, postpartum hypocalcemia, periparturient hypocalcemia, and puerperal tetany) is an acute, life-threatening condition seen at peak lactation, two to three weeks after whelping. Small breed bitches with large litters are most often affected. Hypocalcemia may also occur during parturition and may be a cause of dystocia. Supplementation with oral calcium during pregnancy may actually predispose to eclampsia during peak lactation; excessive calcium intake during pregnancy causes a down-regulation of the calcium regulatory system, which can subsequently produce clinical hypocalcemia when calcium demand is high. The typical bitch affected with eclampsia has been healthy during early lactation, and the neonates have been thriving. Early clinical signs of eclampsia include panting and restlessness. Mild tremors, twitching, muscle spasms, and gait changes (stiffness and ataxia) result from increased neuromuscular excitability. Behavioral changes such as aggression, whining, salivation, pacing, hypersensitivity to stimuli, and disorientation are frequently seen. Bitches may become hyperthermic from panting and tremors, and increased heart rates, excessive drinking and urinating, and vomiting may occur. Severe tremors, tetany, generalized seizure activity, and finally coma and death may occur. Eclampsia can be difficult to differentiate from other diseases (such as hypoglycemia, epilepsy, encephalitis, or toxicosis), so whenever the bitch appears to be having nervous system symptoms, alert your vet. Intravenous calcium therapy should produce muscular relaxation and clinical improvement within 15 minutes. Follow-up treatments will likely include more calcium administered subcutaneously, and then oral calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Once a bitch has eclampsia, she is likely to have it again in subsequent pregnancies. Prevention consists of an appropriate diet during pregnancy and lactation – that is, a high-quality, nutritionally balanced diet with no additional calcium supplementation. Food and water should be provided without limit during lactation, and puppies should be supplemented with milk replacer early in lactation and with solid food after three to four weeks of age. Calcium supplements may be appropriate for the bitch during peak milk production, especially for one with a history of eclampsia. Homeopathic veterinarians have reported some success preventing eclampsia by using a low potency of one of the calcium salts during the later stages of pregnancy and up through lactation. Corticosteroids lower serum calcium, and may interfere with calcium intestinal absorption and increase urinary calcium loss. Thus, for several reasons they are contraindicated at any time during pregnancy and lactation. Mastitis is inflammation of the mammary gland(s) associated with bacterial infection. It may be localized in one gland or within multiple glands, and is caused by a number of bacteria, commonly E. coli or staphylococcal species. Conventional treatment consists of antibiotics; realize that whatever antibiotics used will appear in the milk and be ingested by the puppies. Alternative treatments include acupuncture, homeopathic, and herbal remedies. (Homeopathic remedies and acupuncture have both been shown to be effective when treating dairy cows, a species where mastitis is very common.) Prolonged delivery, dystocia, and/or retained fetuses or placentas may lead to metritis, infection of the uterus. There is usually a purulent discharge from the vagina, and a variety of bacteria have been isolated from infections. Affected bitches are usually depressed, feverish, and lethargic, and they may refuse to eat. Pups may also show signs of restlessness, and they may cry incessantly. Metritis can lead to severe systemic illness that requires stabilization of the bitch with fluids along with antibiotics and other supportive care. Pyometra is a hormonally mediated disorder characterized by cystic growth of endometrial tissue with secondary bacterial infection. It is reported primarily in older bitches, more than five years old, and it typically occurs four to six weeks after estrus. It is often associated with the administration of long-lasting progestational compounds that are used to delay or suppress estrus, or to the administration of estrogens meant to cause abortion in mismated bitches. Infections after breeding may also be a cause. Symptoms are variable and may include lethargy, refusal to eat, dehydration, and excessive drinking and urinating. Sometimes the cervix is open during the infection, and in this case there will be a mucopurulent vaginal discharge; if the cervix is closed, there will be no discharge. Only about 20 percent of affected bitches run a fever, but some go into shock. The results of a complete blood count can vary. The kidneys may indicate temporary signs of failure. Ultrasound or radiography will confirm the condition. Pyometra is common enough that it should be considered any time an illness exists in an intact female, especially if the illness occurs about a month after estrus or after employing hormone treatments. Ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice; medical management is possible, but it may prove to be difficult and costly. Mammary tumors are a common occurrence in female dogs – about three times more common than in women. They comprise about 50 percent of all tumors that occur in female dogs. The exact mechanism of their causation is unknown, but hormones may play an important role. Obesity has been implicated as a contributing factor. Mammary tumors are most frequent in intact bitches. Ovariectomy before the first estrus reduces the risk of mammary tumors to 0.5 percent of the risk in intact bitches; ovariectomy after one estrus reduces the risk to 8 percent of that in intact females. It is assumed that neutering the bitch after maturity leaves her with the same risk as intact bitches, and although it is often recommended to spay the bitch at the time of tumor removal, the true impact of this recommendation is unknown. More than 50 percent of canine mammary tumors are benign. However, since it is often difficult to determine the degree of malignancy of a mammary tumor, from a practical view, all of them should be treated as potentially malignant. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Attempts at chemotherapy have not proven to be consistently helpful. Alternative remedies such as acupuncture and/or homeopathy have also been used, with variable success. Prognosis depends on several factors, including the size of the tumor, its spread to other tissues, and the potential for malignancy. Most mammary tumors that are going to cause death do so within a year. Since mammary tumors can be life-threatening, and since they are fairly effectively prevented by early spaying, this is one more reason to have your female dog spayed at an early age. Alternative therapies Acupuncture, homeopathic, and herbal remedies have been used for thousands of years to enhance pregnancy, ease the birthing process, stimulate lactation, and treat diseases of the female reproductive tract, the pregnant female, and the pups. Historically, many herbs have been used to cause abortion, so it is important to check with a holistic practitioner before using any remedy, natural or otherwise, during pregnancy. Perhaps the Big Momma of all alternative remedies for pregnant females is the homeopathic remedy, pulsatilla. Practitioners use it to prevent premature birth, ease birthing, calm mothers during whelping, help pass placentas, and instigate lactation. I’ve been so impressed with it I routinely recommend it for all mothers – dogs, cats, horses, donkeys, pigs, etc. – at a medium potency of perhaps 30c three times, 12 hours apart, beginning shortly after birth or during birth if there is any difficulty encountered. -Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.