Osteosarcoma (OSA) has been found in every vertebrate class and has even been identified in dinosaur fossils, but it appears to be more prevalent in dogs than in any other species. While there are different types of bone cancer, more than 85% of the bone malignancies diagnosed in dogs are OSA.

When compared to other types of cancers found in dogs, the incidence rate of primary OSA is low, with an estimated 10,000 dogs newly diagnosed each year. Its survival rate varies considerably depending on which treatments are used, but, unfortunately, none of the current treatments have high rates of success. Many promising new treatments are in the works, however.

The most common clinical signs associated with OSA are pain, swelling, and lameness in the affected leg. Lameness occurs due to pain, inflammation, microfractures, or pathologic fractures (fractures caused by normal movements due to bone deterioration caused by disease). If swelling is present, it is likely due to the spread of the tumor into the surrounding soft tissues.

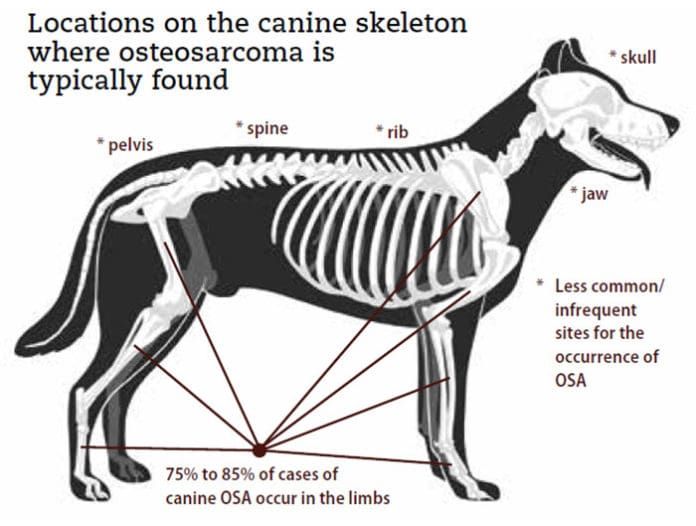

Where OSA Is Found

OSA can develop in any bone, but the most common form – the appendicular (limb) form – occurs in the long bones of the legs and accounts for 75 to 85% of cases. Within this subtype, the rate of occurrence in the forelimbs is twice that of the hindlimbs, often located at the top of the humerus (shoulder) or the bottom of the radius (wrist). On the hindlimbs, knee and ankle areas are common locations. These locations are at the ends of bones, at or near the growth plates where cell turnover is high during growth.

While the majority of the remaining cases occur in the axial skeleton (the bones of the head and trunk), there have been cases of OSA documented in extraskeletal sites including the skin and subcutaneous tissues, as well as the lungs, liver, mammary glands, and other organs and glands.

[post-sticky note-id=’365174′]

Osteosarcoma affects mostly middle-aged and older dogs; 80% of cases occur in dogs over 7 years of age, with 50% of cases occurring in dogs over 9 years old. Younger dogs are not immune; approximately 6 to 8% of OSA cases develop in dogs who are just 1 to 2 years of age. OSA of the rib bones also tends to occur in more often in younger dogs with a median age of 4.5 to 5.4 years.

Cause

As with most canine cancers, the cause is unknown. There has been no gender predisposition documented. There does appear to be a genetic component as OSA predominates in long-limbed breeds. Large and giant breeds have an increased risk of OSA because of their size and weight. Small dogs can develop OSA as well, but it is far less common.

Notably, the forelimbs support about 60% of total body weight of the dog and are the most common limbs to develop OSA. It is theorized that in addition to body size, the fast growth rate to create the longer bones in large breeds might contribute directly to OSA risk. Rapid bone growth results in increased bone remodeling and increased cell turnover; high cell division and turnover occurs naturally at and near the growth plates, which are also the most common sites for tumor development.

A dog’s risk also appears to increase if he has had surgery for a fracture repair or an orthopedic implant. These conditions spur the proliferation of bone-forming cells. OSA also has been associated with fractures in which no internal repair was performed. Other possible causes include chronic bone and bone marrow infections, microscopic injury in the weight-bearing bones of young growing dogs, ionizing radiation, phenotypical variations in interleukin-6 (a protein produced by various cells), abnormalities in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene, viral infections, and chemical carcinogens.

Hormonal risk factors are being actively explored in an effort to determine if there is an increased risk for OSA based on the age of spay or neuter (gonadectomy). In May 2019 Makielski et al. authored a comparative review of OSA risk factors and included this commentary on trending current hormonal studies (Veterinary Sciences Vet Sci 2019, 6, 48):

“Similarly, associations between reproductive status and development of osteosarcoma have been inconsistent. Although several reports suggest that spayed and/or neutered dogs have higher incidence of certain cancers, including osteosarcoma, the relationship between reproductive status and cancer risk may be confounded by other variables, such as the documented tendency toward increased adiposity and body condition in gonadectomized dogs. Increased load combined with delayed physeal (growth plate) closure, a result of gonadectomy prior to skeletal maturity, could theoretically contribute to increased osteosarcoma risk in dogs.”

Diagnosis and Staging

Clinical presentation of canine OSA typically appears as lameness of the affected limb, with or without visible swelling or mass at the affected area.

[post-sticky note-id=’365169′] Diagnostic exams usually include a physical exam, an orthopedic and neurological examination (to eliminate other causes of lameness), and radiographs (x-rays). Radiographs may allow for a presumptive diagnosis as OSA frequently has a characteristic appearance in the bones: patterns of bone destruction, abnormal bone growth, and sometimes fractures.If a tentative diagnosis of OSA has been made, additional screening tests are recommended to ensure your dog is otherwise healthy; these may include a blood panel, thoracic radiographs, and CT scan. Ultrasounds are often performed but early metastasis to the abdomen is very rare. A bone aspirate for cytology with alkaline phosphate stain is common and recommended. This may occur as part of the screening process or obtained during surgery.

OSA is extremely aggressive and typically metastatic. While only 10 to 15% of dogs will have measurable metastasis, it is believed that up to 95% of dogs have undetectable metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Because of this high metastatic risk, additional assessment is recommended. Most metastatic spread appears in the lungs so thoracic radiographs are warranted. Survey radiographs also may be recommended due to an 8% risk of metastasis to other bones. Metastasis may also be seen in lymph nodes (5%) and internal organs.

If available, PET scans or nuclear scintigraphy (sometimes referred to as a “bone scan” or “Gamma scan”) are even more sensitive diagnostic tools that can identify diseases not visible with other imaging methods. It can be useful for the detection of metastasis in dogs as it can distinguish any region of osteoblastic activity, including osteoarthritis and infection.

While there are several published histologic grading systems for OSA, there is no universally accepted system, making the predictive value of routine grading of OSA questionable.

Staging of OSA utilizes the TNM (Tumor-Node-Metastasis) System, the standard system used for most tumor staging in veterinary medicine. Three stages of OSA can be differentiated:

Stage I indicates a low-grade tumor (G1) with no evidence of metastasis (M0)

Stage II indicates a high-grade tumor (G2) without metastasis.

Stages I and II are further divided into two subgroups: Group A indicates that the tumor has stayed within the bone (T1). Group B indicates that the tumor has spread beyond the bone into other nearby structures (T2). Most dogs are diagnosed with Stage IIB OSA.

Stage III is a tumor with metastatic disease (M1).

Treatment

The primary considerations for treatment of OSA should include an understanding of how far the disease has metastasized, how to treat the bone tumor itself, and how to curb, delay, or prevent recurrence or spread of the disease. The disease develops deep in the bone and destroys it from the inside; as a result, it can be extremely painful and treating that pain can be a challenge. Above all, any approach should ensure that the dog maintains excellent quality of life.

- Surgical

Wide-margin surgery, by either limb amputation or limb-sparing surgery, is indicated as the standard initial treatment of canine appendicular OSA. While biopsies are typically recommended prior to surgery for most types of cancer, it is not a necessity with OSA when there are other diagnostic indicators.

- Amputation

Removal of the limb extracts the local cancer immediately and is the quickest and most effective way of alleviating pain and most of the destructive processes of OSA. It also removes the risk of a painful pathological fracture, which often occurs as the disease progresses.

Because pain inhibits quality of life, amputation is considered a quality of life choice. The majority of dogs recover quickly and resume a normal life on three legs. Amputation completely removes the primary tumor, is not a complicated surgery and requires less anesthesia time, offers a decreased risk of postoperative complications, and is a less expensive procedure than limb-sparing surgery (discussed next).

- Limb-Sparing Surgery

Limb sparing can be preferable to amputation for dogs who suffer from existing severe orthopedic or neurological diseases; candidates for limb-sparing surgery should be in otherwise good health with a primary tumor confined to the bone. This surgical procedure replaces the diseased bone with a metal implant or bone graft or combination of the two to reconstruct a functional limb.

[post-sticky note-id=’365172′]Limb sparing surgery temporarily improves the overall condition of the leg, but eventually the cancer will progress and the bone will deteriorate. Limb function is preserved in more than 80% of dogs. However, complications are fairly common with this procedure. Infections occur in 30 to 50% of cases, implant failure in 20 to 40%, and 15 to 25% of dogs will experience tumor recurrence. Subsequent chemotherapy and radiation treatments also may be recommended.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery (aka SRS, Stereotactic Radiotherapy/SRT, Cyberknife)

Stereotactic radiosurgery is an alternative to amputation or limb-sparing surgery; it also may be used as an adjunct therapy following amputation. It is a nonsurgical procedure (but does require anesthesia) that delivers radiation directly to the tumor site. Radiation acts by making cancer cells unable to reproduce.

SRS precisely transmits several beams of radiation aimed from various angles to deliver a high dose of radiation to a designated tumor target. The delivery system is effective and efficient and therefore reduces the chance of damage to surrounding normal structures and tissues. Potential downsides to SRS include fracture from radiation-induced bone degradation and possible tumor regrowth. Early reports suggest that the outcomes of SRS followed by chemotherapy may be comparable to those achieved with amputation and chemotherapy.

- Chemotherapy

The best outcomes for dogs with OSA to date have been for those undergoing amputation followed by chemotherapy. Since tumor removal does not address metastasis, systemic treatment via chemotherapy can be vital to a treatment plan. Several studies have reported prolonged survival rates using cytostatic drug protocols, with carboplatin, cisplatin, and doxorubicin the most commonly used.

Side effects from chemotherapy tend to occur infrequently; when they do, they are usually predictable, minor, and manageable. A dog undergoing chemotherapy can expect to have excellent quality of life.

- Immunotherapy

For the latest in immunotherapy treatment for OSA, see WDJ March 2019 “A New Bone Cancer Vaccine for Dogs.”

Other Treatments

- Palliative Radiation

The primary goal of palliative radiation is to maintain good quality of life for cancer patients, whether human or canine. It is used to control clinical signs and pain associated with tumors that either cannot be treated by other techniques or where more aggressive treatments have been declined.

As an added benefit, palliative radiation may slow the rate of progression and reduce the size of the tumor, thereby further contributing to the well-being of the patient. Dogs with OSA initially undergo two to five treatment sessions (requiring anesthetic) and are typically administered in lower dosages than that used for stereotactic radiosurgery.

Most dogs will achieve some degree of pain relief within the first one to two weeks following treatment, with the potential for it to be effective for a couple of months. When pain returns, radiation can be re-administered for if deemed appropriate.

- Bisphosonate Drugs

Bisphosphonates, such as pamidronate and zoledronate, are easily administered through intravenous (IV) infusions and are aimed at preventing or slowing bone destruction and reducing pain and risk of fracture, therefore prolonging the dog’s life. This treatment is relatively inexpensive, has a wide safety margin, and can even be used on dogs with renal or liver insufficiency.

These drugs are usually used in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy but may be used alone. Additionally, bisphononates appear to have potential cancer-suppression effects by impeding proliferation and inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death); as a result, they have become a targeted area for new research.

- Pain Management

Again, because OSA can be extremely painful, recognition and alleviation of pain is essential for maintaining quality of life. Dogs with OSA may experience pain due to a number of causes: the cancer itself, a treatment modality, or a concurrent disease such as osteoarthritis. To preemptively and adequately control pain, more than one medication is often required.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are typically a mainstay for controlling pain – but aren’t the best choice for the type of pain associated with OSA. However, they may be used to address other forms of pain being experienced concurrently. Gabapentin, amitriptyline, duloxetine, and amantadine are better suited to alleviating OSA-related pain.

Weight control can help by relieving the extra pressure on joints; supplements also may be recommended to help support the unaffected joints. Physical therapy and massage can be beneficial, especially for the compensating joints and muscles. Acupuncture, having been shown to increase endorphins (which inhibit pain perception), also can provide an avenue for pain management.

Palliative Care

Palliative care is an approach that prioritizes measures to relieve symptoms (without curative intent) and improve comfort. It is a valid and respected choice for care; only owners can decide what is best their dogs. Palliative care also can be provided to dogs who are at the end stage of their disease.

Prognosis

The heartbreaking reality is that the vast majority of dogs affected by OSA will succumb to the disease or be released through euthanasia due to disease progression. Dogs who do not receive any form of cancer-specific treatment are usually euthanized within one to two months of diagnosis due to uncontrolled pain.

Those treated with surgery alone (amputation) have an average survival period of about four to five months; almost all die within a year and only 2% live past two years.

Dogs receiving surgery and chemotherapy have average survival times of approximately 10 months, with up to 28% alive after two years.

The median survival time for dogs receiving radiation therapy and chemotherapy is about seven months.

In general, dogs between 7 and 10 years old tend to have longer survival times than younger and older dogs.

The prognosis is very poor for dogs with Stage III OSA; the average survival time is 2.5 months. Dogs less than 7 years old with a large tumor located at the top of the humerus also have a very poor prognosis. Dogs with axial OSA have an average survival time of four to five months as complete surgery is usually prohibitive due to tumor location and likely recurrence. If regional lymph node metastasis has been found, survival time is only about 1.5 months.

This Is A Tough One

With the increasing amount of research being conducted on OSA, there is hope for new therapies, increased survival times, and improved outcomes. But for many, it won’t be soon enough. Bear, my friend Keri’s dog, succumbed to OSA while I was writing this. He lived 16 months after diagnosis with palliative care and lots of love. He is very much missed.

I have my six year old female Faith, Shih Tzu Yorkie breed on Go Venision from Petcurean a company in Canada for 12 and 1/2 months. Prior it was Canine Caviar Venison for three months until company resources depleted and then before than on Fromm Salmon.

Faith has had repeated anal gland issues with scooting even after expression. She also has allergies probable grass for her feet so a limited protein was suggested by vet hence my research into GO by Petcurean.

Recently hér vulva has been pinkish rd and a urinary test was done that her ph was not good and she had developed the red crystals type. She has been on apoquel for a year 1/4 tablet at evening for the anal gland and foot allergies and since 7/20/19 Rheumacan once daily by syringe as disposed by vet.

I also give hér the fruitables canned pumpkin for dogs daily plus tiny fruitables pumpkin and blueberry treats periodically.

The vet wants me now on a vet diet for the urinary tract but my research Indictated just purine with a new bag label and same ingredients. So then it was suggested the hypoallergenic and urinary tract diet to help her.

I am not confident with Hills nor Royal Canine and definitely not Purina.

Since 7/20/19 water has been added to the GO Venison and she loves it as well as if she does not go to hér dish immediately and the kibble starts to soften, I have sprinkled a wee amount of ground flax meal. Lentils, chickpeas, chickens root, are in the Go Petcurean.

Can you advise me the best dog food for Faith allergies that would both help her anal gland issues ns now urinary tract issues. Respectfully, Sharon Findlay

I have no website only email and an old iPad.

This was one of the most informative articles on OSA I have found yet..as a long time greyhound owner I have experienced loss of two of my dogs over the years and wondered “what if” when it came time to decide on treatment choices. Hopefully in the years to come we find a cause and more treatments for this horrible disease.

So typical. Western med vets decide osteosarcoma is a death sentence. My GSD got this cancer at the age of 5. We had her front right leg amputated; 6 bouts of chemo AND took her to a naturopathic vet that worked on building her immune system through an organic diet and supplements. She lived for 5 years and died at age 10. The naturopathic vet has seen these results over and over (one dog lived 8 years after diagnosis) but the traditional veterinarians would give her zero credit for my dog’s longevity simply saying “we have never seen anything like this.” If your dog gets this cancer please consult a legitimate naturopathic veterinarian. There is hope – it just isn’t found with western veterinary medicine.

I lost Tommy, my heart dog, to OSA 2 years ago, when he was 10 years old. After receiving the heart-breaking diagnosis, we had his front leg amputated and followed that with chemotherapy. He lived for 16 months after his initial diagnosis.

After going through this experience once, if I had another dog diagnosed with OSA, I would not go through amputation and chemo again. Amputation and chemo were very hard on my dog. It would be one thing if going through was a cure. And while I loved those extra 16 months, I now wonder, who did I do that for – him or me?

For anyone dealing with amputation, I found the tripawds website extremely helpful .

Dagmar- I lost my heart dog to OSA in his femur 8 years ago. I chose palliative care since it had metastasized to his lungs. But looking back and after reading this excellent article, I wish I had chosen amputation and chemotherapy. But you chose that option and regret it. I think we will always worry we didn’t do enough or didn’t do what was best for our beloved best friends, but we were sincerely doing what our hearts thought were best at the time. OSA is so heartbreaking. Thank you for your perspective.

Dagmar and Carol,

I went through the same thing with my almost 12 year old Lab. Looking back, I don’t know if I would do it again. Or maybe just do the amputation. The chemo was a little rough on him.

If I did, I definitely would do physical therapy after the amputation. He had a hind leg removed and eventually his other hip gave out. He lived 5 months after diagnosis. I regret not thinking of PT at the time. My husband says he’d never do it again. I feel like my Lab had 5 more mostly happy months. It was hard at the end, though. It’s easy to look back and think of all the things we did wrong. I did the best I could with the info I had at the time. It’s still heartbreaking and I haven’t been able to get another Lab after that.

Christine – My husband also said that he never wanted to go through amputation and chemo again. For us, the first 2 weeks after amputation were really awful (as my dog had bad reactions to several of the pain medications – though our vets were wonderful and helped us manage this) and his last month when we knew the end was coming and he was having a harder time getting around.

I was so devastated by the diagnosis that I would have done anything to have more time with him. I don’t regret what I did – I think I would have always wondered if I hadn’t had his leg amputated and gone through chemo. But amputation is a big deal and chemo can be tough on dogs. I guess my point is to know your dog and research your options.

I still can get teary-eyed seeing black Labs who remind me of my Tommy and I too haven’t been able to add another Lab to our family. OSA is such a cruel disease.

Excellent, highly informative article! Thank you SO much. My 3 year old (intact female, but no intention of breeding) Black German Shepherd is my heart and joy and I turn to WDJ for your many helpful and insightful articles. I recently started cooking for her as her kibbles were becoming less and less of interest to her. Now she eats like a champ, every meal (of which there are two/day) although a bit tedious (much easier to just scoop a bowl full of kibble than cooking) I’m glad I made the switch.

I recently lost my sweet 5 year old amstaff mix last week after her amputation surgery. Her first biopsy with the oncologist did not find the cancer and suggested possible fungal infection of the bone or vascular damage, but ruled out cancer. I went to a different vet and tried different options before diving back to another biopsy and when I finally did the 2nd biopsy it was found to be OSA. After hearing all the amputation success stories via online and through people I knew- I immediately jumped on it since time was already wasted. The surgery was a success, but hours later my girl died of abnormal clotting. This truly is a horrible disease. Looking back- I wish I was better informed on the risks, etc. before diving into the surgery. Everyone seemed so enthusiastic and promising as far as the surgery went that I was in total shock with how her body responded. My thing is to always ask more questions and make sure to run every test possible (bloodwork, etc.) to rule out any metastasis other than just doing xrays prior to surgery or to help in making the best decision.

This information will help me in making my decision My sweet baby was diagnosed with low grade cancer. She is 10 years old, I feel we should do nothing. But I am worried about her being in pain . This came on so fast , we were not prepared for this. I don’t want to she go through treatment. We don’t know if we are making the right decision.

Oh no more and more dogs get diagnostics with cancer.

We were just advised our beautiful 8 year old Doberman has OSA in her back right femur and apparently hasn’t spread to the lungs. She has been limping for about two months and the vet couldn’t find the problem. She broke her femur when she was 11 months old and has a plate which we thought was the issue but x-rays showed nothing but the latest x-rays from a different vet showed the cancer. I can’t fathom having her leg amputated and still die in three months. Shouldn’t blood work have shown the cancer? I’m totally distraught and just want what’s best for my dog and by the way my previous Doberman died of the same thing 10 years ago.