If you had to choose one behavior as the single most useful one among all the behaviors you have taught your dog, which would it be? We asked that question of a half-dozen professional positive pet trainers, and not surprisingly, got a half-dozen different answers.

288

My own choice would be the “Wait” behavior. A puzzling choice, perhaps, for a trainer who professes to value relationships with dogs based on asking them “to do” things rather than “not do” things, but my choice, nonetheless. In a multi-dog household, this is an invaluable cue. I use it when I come downstairs in the morning, asking the pack to “Wait” on the landing so I can make it to the bottom of the staircase without tripping over multiple furry bodies. I use it at the door, asking those with less-reliable recalls to wait while the more-reliables go out first to enjoy a bit more freedom. Then Bonnie must wait while 14-year-old Missy, with mobility issues, trundles down the three stairs to outside. Finally, Dubhy and Bonnie are released to go out, with me following right behind to keep them under my direct supervision. We use “Wait” multiple times as we do barn chores, carrying hay, moving horses and pushing wheelbarrows out the gate while leaving the dogs in the barn. And so it goes throughout the day.

Another “Waiter”

Trainer Cindy Mauro, of Bergen County, New Jersey, whose household also includes multiple dogs, agrees with me about the value of “Wait.” (Mauro is shown here with three of her dogs waiting on cue at the top of her front stairs – a valuable behavior when said stairs are icy!) Mauro suggests that “wait” is also invaluable to prevent dogs from flying out of open car doors and to keep them calm on walks. We both teach it initially with a food bowl, and then generalize it to doorways and other scenarios. Here’s how:

288

With your dog sitting at your side, hold her food bowl at chest level and tell her to “Wait!” Use a cheerful tone of voice, not a threatening one. Move the food bowl (with food it in, topped with tasty treats) toward the floor two to four inches. If your dog stays sitting, click your clicker or use a verbal marker, raise the bowl back up to its original height, and feed her a treat from the bowl. If your dog gets up, don’t click! Say “Oops!” instead, and ask her to sit again. “Oops!” is a “no-reward marker” – it tells her that getting up didn’t earn a treat – the opposite of a clicker or verbal reward marker, which tells her she did earn a reward.

Now lower the bowl two to four inches again, click and treat. Repeat this step several times until your dog consistently remains sitting as you lower the bowl. Gradually move the bowl closer to the floor with successive repetitions, returning to full height to feed the treat after each click, until you can place it on the floor without your dog trying to get up or eat it.

Finally, place the bowl on the floor and tell her to eat. The beauty of this exercise is that you have two built-in obvious practice opportunities every day (if you feed your dog twice a day, as I do).

288

When your dog will wait reliably for her food bowl, you can begin to “generalize” the cue by practicing at the door – another natural practice opportunity, since most dogs go in and out of doors several times a day. Ask her to sit at the door, and tell her to “Wait” – cheerfully! Reach for the doorknob. If she stays sitting, click and treat. If she gets up, say “Oops!” and ask her to sit again.

288

When she will stay sitting, increase the difficulty by touching the doorknob, jiggling the doorknob, opening the door a crack, and gradually increasing the amount you open the door. Click and treat several times at each increment before proceeding to the next step. As with the food bowl, if your dog is having trouble succeeding, back up, and take smaller steps.

288

Place

C.C. Casale, PMCT, CPDT-KA, of SouthPaw Pet Care LLC in Charleston, South Carolina, puts “Go to your place!” at the top of her list. She explains that this behavior became very necessary when her Rough Collie, Valentino, joined the family and taught Rocco, her Sicilian Greyhound, how much fun it can be to bark at people approaching the front door or ringing the doorbell.

Casale says, “I taught this skill by capturing the behavior when it was naturally offered by either of our two dogs. The plan was to use this behavior when someone visited our front door so we could keep the dogs safe, away from the open door, and in a settled position, to prevent over-excitement. My husband and I already allowed our dogs to lie on our living room loveseat, which is covered with a fur-friendly slipcover. It was an obvious choice to teach them to ‘Place,’ based on proximity to the front door and their predisposition to enjoy staying in that location.

First, I used a cue they know, ‘Up,’ and practiced the behavior by having them jump up on the loveseat when cued, followed with a prompt of my outstretched arm and finger pointing to the couch cushion. I then changed the cue to ‘Place’ by saying it after the cue ‘Up’ and using the same visual prompt of my outstretched arm and finger. After repeating this to reliability, I removed the ‘Up’ cue, and only used the verbal ‘Place’ cue with prompting. The last step was to remove the prompt after they both reliably offered the behavior when asked, 8 out of 10 times.

“Next , I had someone they know very well (my husband) approach the front door and then walk away. I gradually increased the stimulus by having him open and close the front door and walk away, then enter and walk away, and eventually ring the door bell and enter our home. I then generalized the behavior by having a neighbor the dogs knew well repeat the entire process until they were able to stay in ‘Place.’

Next, we asked another neighbor they’d met but didn’t know well to do the same. The final test was doing the exercise with strangers like delivery men.

288

“Finally, we needed to generalize the behavior to other locations. To do this, I took each of their flat rectangular beds and placed them on the loveseat. This created a smaller visual marker upon which they could practice ‘Place.’ It also gave us a portable ‘Place’ mat we could use anywhere. We now take their beds with us wherever we go, and ‘The Boyz’ have a ready made ‘Place’ when we need them to settle for a while. This is very helpful when going to dinner at friends’ homes, and in the vet office waiting room. A small bath mat or yoga mat cut in half work well as place mats; both are easy to roll up and carry anywhere.”

Recall

Coming when called is a likely choice of a “most useful” behavior for many trainers and owners. This invaluable behavior adds a layer of safety to any dog’s world, and allows canine family members to enjoy a greater degree of freedom. Lisa Waggoner, PMCT2, CPDT-KA, of Cold Nose College in Murphy, North Carolina, was reminded of the importance of a good recall when a new puppy joined her family.

Waggoner says, “A solid recall has allowed me to feel comfortable with Willow in many environments, including large indoor environments as well as outdoor environments, and to have confidence that while working off-leash, I can easily recall her to me. I’ve started calling it a Rocket Recall Recipe. I love training it and I love maintaining it.

“It’s a learned behavior, just like any other behavior I want to teach a dog. I classically condition the dog’s name by pairing it with high-value food so that I get a whiplash turn to me when I say the dog’s name.

Bonita Ash of Ashford Studio

288

“Then I classically condition the recall cue by pairing it with very high-value food (for Willow it’s Vienna sausage). My cue is ‘Come, come, come!’ delivered in rapid fire staccato manner – and actually, the ‘m’ isn’t really pronounced, so it sounds more like ‘Co, co, come!’

“After conditioning the cue, I then say the cue and run away from the dog, taking advantage of her natural desire to chase. When she follows, I click and deliver six to eight pea-sized pieces of extremely yummy food, one bit after another. Because I tap into my inner Looney Tunes character, it’s FUN for her! If I have any doubt about the dog following me, I’ll begin on-leash, then transition off-leash, because I want her to be successful so she can get reinforced. I want her to get it right.

“Practice inside first, so that the recall is very reliable, before ever taking it out of doors. An off-leash indoor recall is like a high school diploma – pretty easy to get. An off-leash, outdoor recall is like a PhD; it takes a lot more work.

“Then practice outside. Because of our fenced acreage I really never did any on-leash work outdoors with her; it was all off-leash. I continued to get her attention by using her name (Willow!); then, when she looked at me, I delivered the recall cue ‘Co, co, come!’ (that’s really what it sounds like), ran away, reinforced heavily with yummy food, then released her to ‘go play’ again. I very slowly increased the distance, then ping-ponged back and forth between short distances and longer distances. I practiced in a variety of environments and always made sure she could ‘get it right’ so that she’d get reinforced for being successful. The environments were at home (indoors and out), at the training center, and at a nearby park (on a long line, then off-leash because it was a safe area).

“When she was consistently successful at returning to me in all of the above locations with no distractions, I began using distractions: Brad (my husband, also a trainer) or Brad and Cody (our other Australian Shepherd) walking in the pasture; another person in the training center; a person a distance away at the park, etc.). I drastically decreased the distance I expected her to travel with each new distraction, then slowly increased that distance as she was consistently successful.

“My next big step was to begin practicing when she was playing with other dogs during our off-leash, outdoor socials for clients and their dogs. Again, wanting her to be successful, I’d wait until she had played for 20-30 minutes and was a bit tired. Then as she was beginning to disengage from a particular play group, I’d say her name, ‘Willow!’ She’d look immediately at me, and I’d deliver my recall cue ‘Co, co, come!’ and run away. Voila! She’d chase me and I’d pay off big time! I slowly increased my distance from her before I delivered the cue and she was successful yet again.

– “When working in a new location, I’d again set her up for success by decreasing the distance, saying her name, delivering the cue, running away, and paying her with a big jackpot.

– The following are more vital ingredients for Waggoner’s “Rocket Recall Recipe.”

Reward all check-in’s indoors (any time the dog happens to come up and say “Hi”). Reward all check-in’s when outdoors, then release to “go play.”

– Never use the recall cue if you plan to do something to your dog that your dog finds unpleasant (such as clipping nails or taking a bath).

Never call your dog if you don’t think your dog will come (i.e., if he’s entranced by the sight of a squirrel or deer).

– If you make a mistake on the above, “save” the recall by finding your inner Looney Tunes character, squealing, clapping, patting your legs while running away from him so that he’ll return to you and you can reward him.

– Never repeat the cue; say it only once and then make yourself as interesting as possible with a high voice, clapping, squatting, squeaking a squeaky toy, etc.

– Always pay off big time, with food or something else your dog loves – a “life reward.”

– Practice, practice, practice!

The following are links to videos of Lisa Waggoner working on “rocket recalls.”

The first two steps of teaching a recall:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=1krg3g-myic

Maintenance practice in a pasture:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=axnjcb2Dn1k

Practice at the beach:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=OW5mM0ARkNI

Practice in a brand new location:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=cR7lPkzkOtQ

Name Recognition

Chris Danker, CPDT-KA, PMCT3, KPA-CTP, of Hemlock Hollow LLC in Albany County, New York, concurs with Waggoner on the importance of name recognition and recalls, and gives additional tips for the name response behavior.

Danker suggests starting on-leash and following these steps:

“Say your dog’s name, then click and treat. Repeat this step hundreds of times. For the first 50 or so repetitions your dog doesn’t have to be doing anything in particular. Start when you are sitting, then practice standing, and take a step or two as you say your dog’s name.

“If your dog has enough deposits in his name-response bank account he will look at you when he hears his name. If he doesn’t, help him out by putting a treat near his nose and luring him toward you. Give him the treat and practice more repetitions with higher-value reinforcers. Use better treats such as freeze dried tripe or all-meat jars of baby food. You want to pay off big for him responding to his name. Save these special treats for your name game training so you keep them special!

“Practice first in all rooms of the house, then outside in a quiet area, and eventually in locations with more distractions. When your dog immediately looks back at you upon hearing his name, add distance. Then take the game outdoors. Your mission is accomplished when your dog will respond in an empty parking lot; when there is other activity around you; even when other dogs or wildlife are around!

Reverse

Sharon Messersmith, owner of Canine Valley Training Facility in Reading, Pennsylvania, chose a less common behavior as her favorite: teaching her dog to back up. She uses his “Back” cue to remove tension on the leash when he’s too far out in front of her, and to get him out of potential trouble spots.

Messersmith says, “I taught my dog (a 105-pound Labrador named Benson) the behavior using a combination of luring and shaping. I started by holding a treat in front of him at chest level, and moving it toward him. He would back up to follow it. Once he began offering the behavior I was looking for I added the word, and started to use it with the luring and prompting. I then taught it to reliability by cueing him to back into the space where he always eats. His dinner was his reward! I then practiced backing him across the deck, up a few steps, across the back seat of the car – anywhere I could think of – and then feeding him. He would walk a mile backward to eat!

“I use this behavior all the time. When he is pulling on the leash, I stop and ask him to ‘Back.’ He will back up into position and we continue walking. I back him out when he is too close to another dog. I back him off the pool steps (from a distance) when another dog is trying to get out of the pool. I use ‘Back’ when in parades, for positioning him for pictures or grooming, or when I need to spread out a carpet or blanket and he’s in the way – any time I need him to move back! When you have a dog who is more than 100 pounds it’s a whole lot easier to ask him to move than to try to physically move him. This saves me a lot of strained muscles with all my dogs.

“At the Peaceable Paws Level 1 Trainer Academy, I learned a new way to teach ‘Back’ – and I prefer it to the method I used for my own dog. This way is all shaping, no luring. Standing a foot away from a wall, I toss a treat between my legs and have the dog go get it. Because the wall is there, he can’t go all the way through. (I can block the sides with boxes or chairs, if necessary). When he backs up, I click, and reward by tossing the next treat between my legs. This sets him up for the next repetition of get-the-treat-and-back-up. When the dog is performing this routine easily I add the cue, ‘Back,’ and eventually can begin using it to elicit steps backward without tossing the treat. I find with shaping I get a lot less sitting and more walking backward.”

Crating

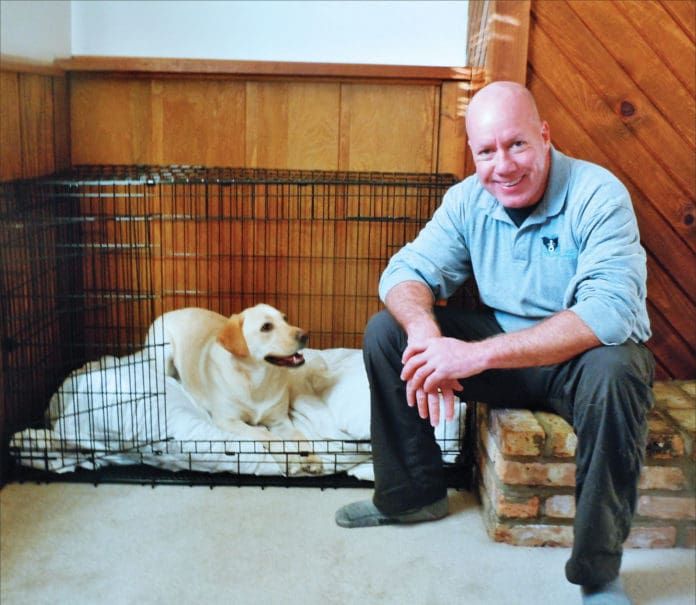

Bob Ryder, PMCT, CPDT-KA, of Pawsitive Transformations in Normal, Illinois, says his Labrador Retriever’s best behavior is going in her crate. Crating is useful for safe travel, stress-free confinement at home or away, and almost mandatory for dogs who need “restricted activity” for medical reasons.

Ryder proudly claims, “Daisy is a world class pro at going to and settling in her crate. It’s one of her favorite behaviors, and comes in handy literally every day, both at home and on the road; in the car, in motels, and in our camper – we take her with us on vacations and for almost all overnight car travel.

“Daisy first came to me as a board-and-train student for clients who couldn’t take her on vacations. I trained her with lure-and-reward techniques, gradually increasing challenges including distance from the crate and distractions such as the doorbell, the presence of guests, etc.

“Our first exercise began with just dropping a few very high-value treats (roast chicken bits) on the floor right about dinnertime when she was hungry. She was allowed to gobble them up with no behavior required other than four feet on the floor. Oops, one or two landed inside the crate while the door was closed and Daisy was locked out. It instantly built her desire to get inside. I quickly opened the door to let her in, and allowed her to come out whenever she wanted.

“After a bit of practice, I started asking her to sit before letting her in. (She already knew the ‘sit’ cue.) After a few sessions (one to two minutes each, all the same day), I dropped a few treats into the crate while she was already inside eating the ones I had dropped while she was outside. Gradually, I increased the time between dropping pieces into the crate, and also cued her to ‘down,’ then ‘down/stay’ while she was in the crate. (She was already fluent at these behaviors.) Once she was solid on the down/stay in crate with the door open, I closed the door briefly while treating, then opened it before she was done finding the tidbits in the blanket folds.

ashfordstudio.com.

288

“Next sessions were done after lots of physical/mental exercise so she was tired, again while she was hungry. I added a frozen peanut butter-stuffed Kong to the equation. While the door was closed she focused on the Kong, then fell asleep for a nap. Several times I called her out of the crate before she awoke on her own, each time unobtrusively dropping a few crunchy treats back in the crate for her to come and find later.

“When it was clear that she was happy to go into her crate, I added a ‘crate up’ cue to ask her to go in. Over time, we played more crate games, using a variety of high-value reinforcers, and cueing her to go to her crate from increasingly greater distances.

“Now, Daisy will literally fly into her crate on cue from anywhere upon hearing our verbal ‘crate up!’ cue. I have cued her from her crate in the car when we’ve arrived home, and she sprints from the car to her crate in my office, bypassing any and all distractions. It’s standard operating procedure now when we have company, when the UPS or pizza delivery guy rings the bell, and when we are eating dinner and want her to settle, without sacrificing tidbits from our plates. Daisy thinks her crate is just great. So do I!”

What’s Your Dog’s MVB?

Your dog’s “most valuable behavior” might not have made this list. Perhaps you found some new ones here to try – and maybe one will steal the Number One slot from your current favorite. What’s important is recognizing that we train our dogs for real-life reasons, not just for high-scoring performances in competition rings, and that the behaviors we teach have real-life value. The bottom line? Teaching your dog useful behaviors enhances the quality of her life – and yours – and all who interact with her.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, CDBC, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She lives in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center, where she offers dog training classes and courses for trainers. Pat is also author of many books on positive training. See page 24 for more information.