No word strikes fear into the hearts of dog owners like bloat. It is a fairly common occurrence and requires immediate intervention and surgical treatment. But what exactly is it? And what should you do if you suspect that your dog is suffering a bloat?

Bloat is the nontechnical term for gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV), a condition in which the stomach rotates around itself to become twisted. The stomach can twist halfway (a 180-degree torsion), all the way leading to a 360-degree torsion, or anywhere in between. Once twisted, the stomach becomes stuck, and fluid and gas cannot exit. A dog cannot vomit, as the entrance to the stomach (the cardia) is obstructed, and nothing can leave the stomach via the intestines, because the exit (pylorus) is also blocked.

Due to this twisting, the stomach rapidly fills with fluid and gas, leading to abdominal distention. As the stomach quickly expands, blood vessels supplying it rupture and lead to hemorrhage. The massive stomach pushes on the diaphragm, making it hard for the dog to breathe. It also causes pressure on the caudal vena cava, which brings deoxygenated blood from the body back to the heart. Without blood circulating, shock occurs rapidly.

Bloat Symptoms in Dogs

The symptoms of bloat are classic and include restlessness, discomfort, pacing, abdominal distention, gagging, salivating, and non-productive retching.

The earliest signs may be as subtle as increased drooling and pacing/restlessness. Frequently, this occurs soon after a meal, especially if the meal is followed by exercise. Certain breeds are more likely to develop bloats such as Great Danes, Standard Poodles, and Dobermans, but any breed can bloat. Sex does not seem to be related.

Bloat is an immediate emergency. The longer the stomach stays twisted, the more damage is done. If twisted long enough, the stomach tissue will die and rupture, leading to spillage of stomach contents into the abdomen.

If you suspect your dog is bloated, an emergency trip to the veterinarian is a necessity. Do not wait overnight to see your veterinarian in the morning. The sooner that GDV is addressed, the better the chances for recovery.

At the Veterinary Clinic

When you arrive, the technical staff should take your dog directly to the treatment area for examination. Bloat can often be determined based simply on signalment (age and breed) and physical examination. The belly will be tight and tympanic (meaning like a drum).

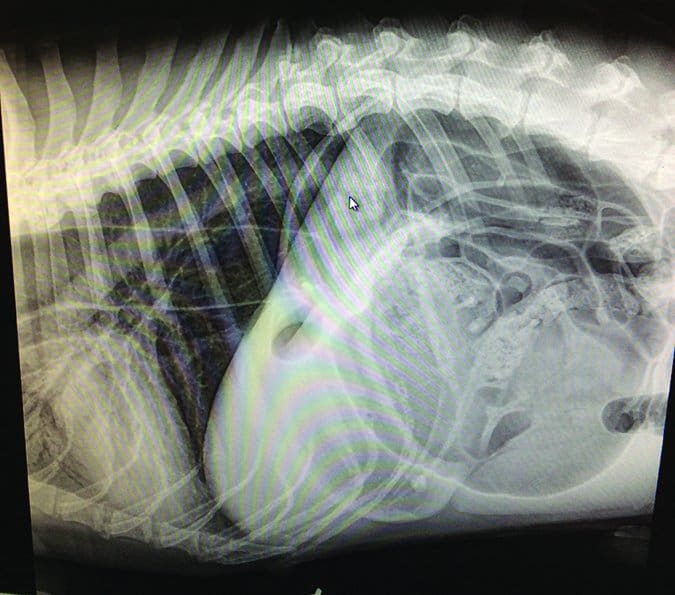

To confirm the diagnosis, your veterinarian may take a right lateral abdominal x-ray. This will reveal a classic “double bubble” – a folded, compartmentalized stomach. They are often called “Smurf hats” or “Popeye arms” because of their characteristic appearance.

Time is of the essence, so your veterinarian will treat your dog immediately. A quick physical exam generally will reveal the following abnormalities: an elevated heart rate, panting or fast breathing, a tight, drum-like abdomen, and abdominal pain.

An IV catheter will be placed to administer fluids and correct shock. Pain medications are needed as soon as possible and may include an opioid such as hydromorphone, morphine, or fentanyl.

As your veterinarian and the technical staff work to stabilize your dog, they will also conduct diagnostic testing. This will include bloodwork to evaluate for internal organ damage, as well as checking blood pressure. In a specialty setting, it’s likely that the veterinarian will also check coagulation factors (your dog’s ability to clot) and blood lactate levels.

Lactate has been extensively studied in GDV. It is produced as a backup source of energy in the body. Lactate is always being produced, but in shock, when oxygen levels are decreased, lactate production is much higher. It can be measured with a hand-held device much like a blood glucose monitor. Many studies have been done to evaluate how helpful this is in determining outcome in GDV patients. Currently, it is thought that a high lactate level that decreases with IV fluids and surgery is a good indication for recovery.

GDV often occurs in older dogs, so your veterinarian also may recommend three-view chest x-rays to evaluate for the presence of any abnormalities. One study showed that 14 percent of dogs with GDV have concurrent aspiration pneumonia, likely from gagging and inhaling drool and watery stomach fluid that can escape the twisted stomach. Many GDV patients are older, and three-view x-rays can also evaluate for metastatic cancer that would make the surgery prognosis poorer. This recommendation is dependent on the vet who treats your dog. Any delay in surgery can be detrimental to your dog, so in cases of elderly dogs (greater than eight years of age) in particular, this recommendation must be weighed carefully.

Stomach Decompression for Dogs

Before surgery, your veterinarian will likely try to decompress the stomach – that is, relieve the gas buildup in the stomach. This can be done in one of two ways. The first is to pass a tube down the esophagus into the stomach – an older but still accepted method. It can often be done in an awake patient. This rapid decompression can help buy time for the twisted stomach. In some rare cases, passing a tube can untwist the stomach, but the procedure also poses the risk of puncturing through the twisted stomach entrance (cardia).

Another method of decompression is called trocarization. In this technique, large gauge needles are inserted through the skin into the stomach to relieve the air. This is currently the more commonly used approach because it is quick, doesn’t require multiple staff members, and can be very effective. It poses a much lower risk to the dog, but is not without risk altogether: it’s possible to lacerate the spleen during this procedure.

There is a great video online of a veterinarian performing trocarization on a Bernese Mountain Dog with GDV.

Surgery for Bloat

The goal in a GDV is to stabilize the patient as quickly as possible before surgery. A GDV can be successfully treated only with surgical intervention. This often puts the veterinarian and owner in a very difficult spot. Decisions must be made quickly and with decisiveness to allow for the best outcome. GDV surgery can be very costly, and most dogs will remain in the hospital for two to three days post-operatively. The prognosis is dependent on each dog and how long the torsion has been present. In general, survival rates for the surgery are high.

Your veterinarian will take your dog to surgery as soon as possible. This should not be done until the patient is as stable as can be expected. To some extent, full treatment of shock is impossible until the stomach is de-rotated in surgery. The patient’s condition should be optimized. This means stabilizing blood pressure, bringing heart rate down to normal or near normal, controlling pain, and decompressing the abdomen either via stomach tube or trocarization.

In surgery, your veterinarian will open the abdomen, identify the twisted stomach, and then de-rotate it. Once de-rotated, the stomach is checked for damage. In some cases, part of the stomach tissue has died and must be removed. The spleen will be checked next. It lies alongside the stomach and shares some blood vessels. When the stomach twists, the spleen does as well. Damage to those blood vessels can lead to a damaged spleen. In some cases, the spleen must also be removed.

Once the stomach and spleen are addressed, the stomach is sutured to the right body wall. This is called a gastropexy. This will prevent the stomach from rotating again in 90 percent of cases. However, in about 10 percent of cases, a dog can still develop a bloat. It is imperative to always monitor your dog for the symptoms of bloat, even when they have undergone gastropexy.

There are several different techniques for gastropexy. The most common is the incisional. This is when an incision is made into the outer layer of the stomach (serosa) and a matching one made on the wall of the body. The two are then sutured together, holding the stomach in place.

Surgery generally lasts about an hour to an hour and a half.

Post-Operative Care

Most dogs will remain hospitalized for one to three days after surgery. Post-operative care will include IV fluids to maintain hydration, pain relief, and close monitoring. Complications can include arrhythmias, hemorrhage, and infection. In some cases, a syndrome called systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome (SIRS) can occur. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a massive and fatal collapse of the ability of the body to clot blood, can also occur.

Patients should be monitored around the clock after surgery, preferably at an emergency and/or referral hospital. Not all veterinary hospitals have staff on duty all night, so be sure to ask your veterinarian if this is something that will be available, or whether a transfer to a clinic with a night staff is possible.

Excellent attention to recovery is important. This will include monitoring of heart rate and rhythm (by ECG), temperature, and comfort level. Most patients are fasted for about eight to 12 hours after surgery. They are then offered a bland, easily digestible diet.

Arrhythmia and Bloat in Dogs

It is very common for a dog that has GDV to suffer from arrhythmias during or after surgery.

The most common are ventricular tachycardia and slow idioventricular rhythm. The ventricles are the lower chambers of the heart. When a dog goes into shock, the heart muscle becomes irritable and can develop irregular beats, particularly in the ventricles. Tachycardia occurs when the heart rate is faster than 150-160 beats per minute. When the heart rate is normal but the rhythm is abnormal, this is a slow idioventricular rhythm.

In most cases, these resolve within a week without specific treatment. If the arrhythmia persists, it is important to have the heart evaluated by a cardiologist. Since Great Danes in particular are prone to both GDV and cardiomyopathies, concurrent heart disease could be present.

Bloat Prevention

Much research has been devoted to this topic. The causes for GDV are poorly understood. At various times, an array of different recommendations have been made to prevent bloat, including the use of raised food dishes, the avoidance of raised food dishes, avoiding exercise after meals, and feeding smaller, more frequent meals rather than one large meal. More recent research has identified a possible link between motility disorders and GDV. At this time, unfortunately, there are no hard and fast rules for preventing bloat.

Prophylactic gastropexy is strongly recommended for the highest risk breed, the Great Dane, as some estimates show one in three will experience GDV. This can be done at the time of spay for females. It can also be done laparoscopically for males at practices that offer this modality.

Standard Poodles, Rottweilers, Irish Setters, and Weimaraners are also considered at-risk breeds for which prophylactic gastropexy should be considered. In other breeds, the benefits versus risks of preventative gastropexy are less clear. But one thing is certain:

No matter what type of dog you own, if you observe the classic symptoms of bloat – restlessness, discomfort, pacing, abdominal distention, gagging, salivating, and non-productive retching – you need to get your dog to a veterinary emergency room ASAP.

Mesenteric Volvulus: A Diagnostic Puzzle

While less common than GDV, mesenteric volvulus is a similar condition that requires immediate veterinary care and can be deadly in a matter of hours. For owners of German Shepherd Dogs and Pit Bulls (the most predisposed breeds) it is especially imperative to know about this condition.

With a mesenteric volvulus, the small intestines twist at their origin (called the root of the mesentery). This leads to obstruction of blood flow and death of the upper GI tract. The cause of MV is unknown. There seems to be an association with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) in which the pancreas does not produce digestive enzymes. However, this has been shown in only one study. Other causes have not been identified.

The symptoms are frequently very sudden in onset and include vomiting, extremely bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain and distention, and collapse in a dog that was previously normal. The gums will be pale, and the heart rate and breathing rapid. The abdomen may be distended and extremely painful. An emergency trip to the veterinarian is warranted. Do not wait!

Unfortunately, these symptoms present a diagnostic dilemma for the veterinarian. Acute collapse can represent several conditions including Addisonian crisis, anaphylaxis, and acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome. If mesenteric volvulus is not identified within one to two hours, death often results. Therefore, if your dog exhibits these symptoms, your veterinarian should conduct treatment and diagnostics immediately.

Treatment for Mesenteric Volvulus

Initial treatment and testing should happen simultaneously when possible. An IV catheter will be placed to administer fluids and correct shock (manifested by low blood pressure, high heart rate, and rapid breathing). Oxygen may also be given by face mask or nasal prongs. MV is an extremely painful condition, so pain medications should be given.

Your veterinarian should also be conducting diagnostics at the same time. X-rays and/or ultrasound of the abdomen are critical in diagnosing MV. Bloodwork should also be done concurrently to evaluate internal organ function, as well as determine the severity of shock and to rule out other diseases. Most MVs are readily apparent on x-ray, but this is not always the case. Ultrasound also can be helpful.

Surgery for Mesenteric Volvulus

The treatment for mesenteric volvulus is immediate surgery. Even with prompt surgery, the prognosis is extremely guarded for survival. While the stomach can be twisted for hours in a GDV and the patient recover, the intestines do not tolerate the lack of blood flow for long. As a result, the veterinarian must intervene quickly and decisively.

This can lead to a hard decision for both owners and veterinarians. The diagnosis often cannot be definitively made on x-rays and ultrasound. It can be heavily suspected based on clinical signs, breed, and testing, but until the doctor performs surgery, it is not always a certainty. As a result, owners are often forced to make a major decision with an ambiguous diagnosis and recovery. Like any major emergency surgery, it is expensive. MV surgery and post-operative care can cost several thousand dollars. This is an excellent example of why it is important that you have a close and trusting relationship with your veterinarian, as well as an emergency fund and/or pet insurance, which can help offset the cost and stress in the case of MV.

If mesenteric volvulus is suspected, your dog will undergo rapid emergency surgery to de-rotate the intestines. If too much damage has occurred and the intestines cannot be saved, a resection and anastamosis (removal of intestines and sewing ends together) can sometimes be done. However, in some cases, the damage is too extensive, and euthanasia is necessary.

Post-operatively, the patient will likely be hospitalized for several days and undergo careful monitoring. After surgery, complications such as sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and organ failure can occur. Thus, it is imperative that patients are observed closely after surgery. Complications can occur for several days to a week afterward.

Mesenteric volvulus carries a very guarded prognosis for recovery. It is critical that owners of German Shepherds and American Pit Bull Terriers be aware of the symptoms and act rapidly if they are noted.

I have a 3 year old, Black German Shepherd and knew about “bloat”, but mesenteric volvulus is new to me. I would fall to pieces if anything happened to my sweet girl. Thank you for this article. I am going to further educate myself on MV. I currently restrict her “play” for one hour before and one hour after she eats (I cook her meals, twice/day, no kibble) and I never ever feed her then immediately leave the house. I’m always there for at least an hour after she’s eaten just to keep an eye on her. I can’t tell you enough how much I enjoy WDJ. I read my issues cover-to-cover when it comes in the mail and frequently search articles on the WDJ website if I have a concern or question. Thank you so much for all you do to help us ensure that our furry family members live a long, happy and healthy life.

Thank you for this information. I was hoping to find some tips for prevention, however. Can anything be done to reduce the risk of bloat? (I have a Labrador Retriever)

Gastroplexy where they suture the dogs stomach to the interior wall of the body to help prevent twisting. I have a German Shepherd and the one thing I do consistently is to keep her calm an hour before she eats and for about 90 minutes after she eats so her food can settle and digest. Just my two cents AND I’m no Vet. 😉

Yes, Debra Patterson is correct. Preventative gastropexy (I believe it’s gastropexy, not gastroplexy) is an elective surgical procedure where the stomach is “tacked” to the stomach wall (muscle). This doesn’t prevent bloat, per se, but prevents the twisting of the stomach on its axis (which is what kills dogs). Again, this is what I understand, I’m not a vet. I work in rescue with Great Danes and Irish Wolfhound, both breeds are at increased risk of bloat and have had dogs bloat in the past, so I’m more familiar with bloat than I really want to be. The preventative gastropexy is expensive and not all vets know how to do it, but what price is saving your dog’s life and it is less expensive than the surgery if your dog actually does bloat. We have had all of our own pet dogs that were at increased risk of bloat gastropexied. If you decide to have this done (and I recommend it highly–we’ve never had an issue with a dog we’ve had pexied), any vet you go to will need to be made aware that your dog is gastropexied because the stomach will be slightly moved from it’s “original” place and it can throw vets off if they don’t know your dog is pexied (they’ll start trying to find out why the stomach isn’t exactly where it’s supposed to be and they’ll do a lot of expensive tests that are totally unnecessary if they know the dog is pexied). To our great sorrow, we did not have an Irish Wolfhound mix we had pexied (because he didn’t have the deep stomach and the conformation that increased bloat risk) and he did bloat. He was quite elderly and had several other health issues when he bloated and the vet told us he wouldn’t make it through surgery, and if he did, the recovery would be too much for him, so we said good-bye to him Broke my heart and I wish to God I’d had it done on him. I will always regret that I chose not to. I will never have another breed at increased risk and NOT have the pexy done.

Our 8 yr old German shepherd, Rexx, was being boarded while I was on vacation. We happened to come home a day early and picked him up. That evening he was very restless and by 11 PM he was vomiting foam. His belly was hard and I knew the signs of bloat. We called our emergency clinic and told them we were on the way. Within a half hour they had a surgical team waiting to go. They fixed the stomach and removed his spleen. Four days of intensive care and $11,000 later, Rexx was going home. A year later he is a happy 87 lb boy. Luck was in his favor. If we hadn’t come home from vacation a day early, he would not have survived the night.

Thank goodness you came home early!! Divine intervention, I’d say. 🙂

Thanks for this article. I’ve witnessed bloat twice in client’s dogs. One dog did not get treated fast enough and died. The other had surgery and her stomach got stapled into place. It is really vital to know what to look for and act quickly.

What are the chances of bloat and MV in Dachshunds and Chihuahuas?

An acquaintance has lost 1 dog, a GSD, to bloat, and had 1 who survived. Both received expensive medical care. She said that frothy foam drool was the primary red flag. I have never had a case, for which I am very thankful. I do not allow exercise for a few hours after eating, which is why I prefer to feed at night, and feed the dogs in separate rooms, as I suspect gulping or hasty eating could make it more likely to occur.

I don’t know if bloat is similar to gastric torsion following colic in horses, but it seems similar, and so similar risk factors could apply: age, less effective digestion coupled with competition for feed with aged and younger animals eating together resulting in older animal gulping food, energetic exercise or rolling on a full stomach causing the full, heavy stomach to flip.

Thank you, Leslie. I have a 3 year old, Black GSD who means the world to me. Your mention of the frothy foam drool will be an immediate “tell” for me. Thank you for sharing!

My 9 yo Pyrenees/Bernese mix had a splenic torsion when he was 6 yo. The vet said his spleen was twisted more than 14 times and removed it. We should have had the vet do a gastropexy then but didn’t. About a year ago, he couldn’t get comfortable and had an abdomin as tight as a drum! I rushed him to the vet where the receptionist told me it would be at least a 90 minute wait. I insisted someone take a quick look at his tight stomach and thankfully my favorite vet came out, thumped his stomach and took him right back for surgery! It was such a hard recovery. He’s very finicky about eating and won’t eat if he’s stressed or in front of people. He lost a lot of weight the first week but then made a full recovery, thankfully!

The first photo shows a dog eating from an elevated dish. From what I’ve read, this is not best practice to help avoid bloat. In one study,

researchers found that in 20% of cases among large breed dogs and in 52% of cases among giant breed dogs, bloat was actually directly related to having a raised food bowl.

I read that article. It was a sham. At the end they state that the research didn’t account for breed type, sex, spayed or neutered which are the proven causes of bloat.

After loosing a bitch 3 days after she gave birth to 12 puppies to bloat. We now have all our dogs tacked by our vet. We travel quite a lot and this way, I feel that a kennel or dog sitter will not have to be totally aware of the dangerousness of this situation. I always brief them, however, of the symptoms of bloat.

My son owned an Irish Wolfhound and we always soaked his dry food, not so that it was mushy, but slightly enlarged with moisture to go with his natural dog loaf and raw beef. He also got a sprinkle of dry food as well, but he was not allowed to drink a lot of water (which we found he didn’t need because of the moistened dry food) and we always fed at night, so he didn’t need any strenuous exercise, not that Irish Wolfhounds do much of that, they are really a couch potato.

My dog a press Camaro 7 years old is suffering with this right now and there’s nothing I can do. I just got evicted living on my sister’s sofa and broke. The fact she cant breath and is in pain is weighing on me so much. There aren’t any pro bono vets in Douglasville or surrounding area so I have to just watch my girl die slowly and painfully. If someone can help please email me asap

i heard maybe gas x might work – ask your vet first and determine dosage. I think it just buys time to get to emergency.

My dog a Presa Canario 7 years old is suffering with this right now and there’s nothing I can do. I just got evicted living on my sister’s sofa and broke. Watching her unable to breath and is in pain is weighing on me so much. There aren’t any pro bono vets in Douglasville or surrounding area so I have to just watch my girl die slowly and painfully. If someone can help please email me asap

Natashaalicia at G mail dot com

678 539 0338

If you cannot afford to properly care for an animal, you should not own one. There are plenty of no-kill shelters around that would provide essential care.

You could have left out the first sentence! Certainly not helpful in this situation.

That’s an awful thing to say to someone in a desperate situation. The reason I’m reading this article is because my dog (an 8 year old Kangal ) has just had life saving surgery for Bloat. Because he had previously had operations on his forearms it was impossible to get insurance for him. We knew that bloat was a real concern so we have always done everything we can to minimise the risk but low and behold he got it anyway. The surgery was £4621.39.

We are not poor but we certainly are not wealthy and have had to make some really huge sacrifices to keep our beautiful boy alive. What your comment is suggested is that if someone falls on hard times even if at some point they could easily afford insurance but not anymore then they should give up their best friend for something that could in theory never happen. I feel really bad for this person because I have spent the last day sat waiting for a call to see if he made it through surgery. Luckily it went well and now he’s recovering. But the truth is if something like this happens again we literally will not be able to afford it. And no shelter in the world would sacrifice 5k for an 8 year old kangal

I lost my 7 yr. old GSD to mesenteric volvulus. He threw up around 11 pm. The next morning I did not feed him and phoned my vet as soon as they opened. I took the first available appointment which was at 3 pm. I choose not to drop him off and leave him as he was a rescue and hated going to the vet. I took him with me to work to keep an eye on him.

He was lethargic but that seemed normal since I knew he did not feel well.

At 2 pm he threw up an enormous amount of stinky brown bloody mess.

I rushed him to the vet but he was already in shock.

I blame myself for not dropping him off in the morning and will never make that mistake again.

All GSD owners should know about this illness.

It did not present like bloat which I was very familiar with from past dogs.

lost our Doberman Irish wolf cross over ten years ago to bloat . took to vet but was miss diagnosed and she died in the car on the way home. she was 11 years young and slightly over weight and had parvo when she was a puppy. same vet saved her then. now we kennel our dogs before feeding and 30 minutes after with no water till time is up. so far so good our Doberman is 7 now and very healthy and active . thanks for all the info you research and allow us to access.

Are Japanese Akita at high risk as well? I’m still unsure what to do about my boy…

Just a comment about not owning animals if you can’t afford to take care of them. I agree to a point and feel that Natasha should have had her dog put down rather than let it suffer even if she had to make payments to the vet. However, over the past 30 years, I have saved over 25 dogs and cats after moving to an area where people took abominable care of their animals. Things have gotten slightly better over the years but not much. I just took in my 9th dog which I hope will be my last as I am living on Social Security for the most part. My animals do not get state of the art vet care but get all initial vaccines and get spayed or neutered. They go to the vet when they need to and after initial vaccines, only get rabies boosters. Most previous pets have lived a normal lifespan of 12 to 16 years, living indoors, knowing they were loved, well fed, warm when it was cold, cool when temperatures blazed. When something major happened, they had to be put down. Considering their fate before I took them in, I don’t think the fact that I can’t afford $11,000 in vet bills should be an issue.

Thank you. People with limited income should definitely be able to adopt and vet schools imo should require a year or two internship at free or low cost clinics before they get credentialed. I mean people that want CASAC credential need several years of clinical hands on counseling before they get full credentials. I also think having animals can be more effective than medication for depression and other issues so would it be that difficult to help senior s and others on limited means with veterinary stipends and food. It is heartbreaking so many are now “surrendering” or abandoning their pets because they cannot afford to feed them.

Please print the many ways we might avoid this happening!

My very first concern has been feeding! Rule…put on wall in front of feeding area:

No exercise one hour before eating and one hour after feeding!

What else can we do to possibly prevent this?

What is the feeling about “fixing” the stomach when neutering?

Just a couple quick lessons learned for my experience with my four cases of GDV. I had three GSDs die from it and one had it twice (the second time the stomach did not torsion, because of gastropexy, but instead gastric motility developed, with lower esophageal sphincter failure and secondary megaesophagus. Some lessons I learned: clear white foamy vomit and restlessness were present in all cases. Twice, the GDV was missed by the emergency vets as simple megaesophagus. It wasn’t until I insisted on a second opinion from a radiological specialist that GDV was revealed – there was no classic double bubble but clear spleen torsion with secondary megaesophagus. In both cases, the vets dragged their feet and when they finally operated too much time had past. They both died on the operating table. If you suspect bloat but the vet says no because they don’t see the double bubble, consider paying the extra for a second opinion for a radiological specialist.

In two cases the bowls were raised, two they were on the floor. In all cases the dogs hadn’t eaten in at least 2 hours before playing.

* I meant gastric motility stopped

There’s a number of slow feeder bowls available now for small and large dogs, which can help in slowing down the rate of eating and preventing gulping – which often results in too much air being swallowed along with the food. My beagle previously had a problem eating way too fast and this bowl did manage to make his meal times more comfortable.

My son’s dog had the surgery and recovery went well but he now refuses to eat. We have tried chicken and rice, eggs, most everything. Any suggestions? The surgery was 16 days ago.

Anyone concerned about bloat should read the Purdue study. Elevated bowls are thought to I crease the chances of bloat by 52%

Karen, that study is now very out of date, raised bowls are not suspect in bloat cases.