[Updated March 4, 2016]

Nine years ago, PETA launched a campaign against the Iams brand. The campaign alleged that the pet food company contracted with an independent, contract laboratory, to conduct unnecessary research on dogs and cats in cruel and unsanitary conditions. PETA released 26 video clips, filmed by an undercover investigator at the lab, showing distressed dogs in small cages, recovering from surgery, anesthetized dogs, and a bag said to contain the body of a dog who died following surgery in an Iams-related test. Thousands of people boycotted Iams pet food to express their outrage at these allegations, and some still associate the Iams brand with cruel animal research.

Iams’ parent company, Procter & Gamble, issued denials about some of the claims made in the PETA campaign – but it also acknowledged that the conditions shown in some of the video clips represented violations of its animal welfare policies. P&G severed its relationship with the lab shown in the videos and with all other contract labs. The company moved all the animals it owned to its pet food research facility in Ohio, and greatly expanded that facility, so that all animals used for P&G research would be under their own supervision and care.

But in some ways, the damage was done. Whether due to exposure to the PETA campaign or to people who learned something (accurate or not) about it secondhand, many pet owners now possess a mental association between “pet food research” and substandard living conditions (if not actual cruelty) for animals involved in pet food research.

This is unfortunate for several reasons. Foremost is that the incident confirmed the instincts of most pet food executives that they should hide (or at least never discuss) any research they do in support of their products, lest they inadvertently expose their companies to criticism (fair or not) or activism. For years, the pet food companies that had the most extensive animal nutrition research programs routinely denied requests for tours of their facilities or detailed information about their research, citing either concerns about the potential for pathogenic infection for the research animals or the need for security from infiltration of animal activists.

The “top secret” status of most corporate pet food research results in obscurity for many nutritional studies that may be of interest or value to pet owners. And people with genuine concerns about or interest in the welfare of the research animals have been largely unable to gather reliable, independently verified information about conditions for the animals in research labs. Is Iams cruel? Pet owners had to decide for themselves which public relations campaign to believe: PETA’s or P&G’s. Some of us were frustrated that those were the only two options!

Transparency is the New Black

In recent years, however, the pet food industry has discovered the benefits of sharing more information about its products, manufacturing, research, and development with consumers. In a highly competitive market, it’s advantageous to project a confident image of full transparency – as long as the company is doing everything they say they are doing.

There are two companies that have embarked on relatively high-profile public relations campaigns to inform consumers about their pet nutrition research. One is P&G. It would be understandable from just a PR standpoint that the company is motivated to improve its image on this front. But after making considerable investments in a total makeover of its research goals and facilities, P&G found itself with a good story to tell. The company began reaching out to pet industry journalists and inviting them to tour its research facility in Lewisburg, Ohio; I accepted its invitation and was a sole tourist, with a half a dozen or so guides, in June 2009.

More recently, Hill’s Pet Nutrition began taking a similar tack, inviting pet-related journalists and bloggers to tour its research facility in Topeka, Kansas. I toured the Hill’s Pet Nutrition Center in March with a group of a dozen or so other dog- and cat-related writers.

I was curious. What sort of research, exactly, are they doing at these facilities? Where do they get their animals? What is the quality of life for the animals? Here’s what I observed and learned.

Procter & Gamble’s Pet Health & Nutrition Center (PHNC)

A public relations person for Eukanuba contacted me for the first time in May 2009, saying that she and a Eukanuba brand manager would like the opportunity to meet with me and tell me about Eukanuba’s pet foods and the direction the company (P&G Pet Care) is taking with its product development. We exchanged a number of emails, and shortly, they invited me to visit the P&G Pet Care corporate offices in Dayton, Ohio, as well as the PHNC in Lewisburg, an hour away.

I was excited. I had failed to wangle an invitation to see the facility in 2005, when I was writing an article about feeding trials, which included a long sidebar about the PETA/Iams dustup (“On Trial,” April 2005). At that time, I had tried to make the case to a PR person for Iams that if the company was confident that the PHNC and living conditions for the resident research animals were as they described, they should welcome the opportunity to prove it. No dice.

Four years later, however, P&G Pet Care offered to pay for my airfare and hotel and provide transportation to its Ohio facilities. WDJ’s publisher, Belvoir Media Group, disallows any such gifts or “sponsorship” – though it will allow me to accept a free meal or two. With my publisher footing the bill, I combined the travel to the P&G sites in Ohio with some other WDJ research-related travel (a tour of a duck processing plant and the WellPet dry pet food manufacturing plant in Indiana).

I arrived in Dayton, Ohio, in the late afternoon. I met the corporate PR person who had first contacted me about Eukanuba, and she drove me to a nearby restaurant for dinner with, oh, 10 or so people from the P&G Pet Care division. There were people who were involved with the animal nutrition research, people who worked with the P&G customer service/technical support staff, and of course, marketing and PR people. Everyone seemed very familiar with WDJ and our dog food selection criteria – including the fact that we’ve never been particularly kind to P&G’s Iams or Eukanuba foods – but they all seemed sincere in wanting to learn more about our readers’ interests and the development of our food selection criteria.

The next morning, I again met the PR person in the hotel lobby and she drove us to one of P&G Pet Care’s corporate buildings in Dayton. (P&G relocated these offices and employees to a larger facility encompassing other P&G divisions in Mason, Ohio, in October 2009.) There, I was introduced to some of the brand managers and marketing staff for Iams and Eukanuba products, and was able to speak at greater length with the clinical veterinarian who oversaw the healthcare provided to the dogs and cats involved in developing many of the Iams and Eukanuba products.

Iams and Eukanuba dog and cat food products are formulated, tested, and promoted by the same people. It’s up to the P&G marketing teams to decide whether new products that are developed will roll out under the Iams or Eukanuba label. Each brand has a slightly different identity in the marketplace, so as new products are conceived, at some point, they are pointed toward one brand or the other.

I also got to talk to some of the customer service/technical support people who answer the toll-free numbers for both consumers and veterinarians who have questions about Iams or Eukanuba pet foods.

One thing I noticed right away about this multi-story office building: there were a lot of dogs accompanying employees to work (I lost count after meeting 15 or so), and it clearly wasn’t a setup on my behalf; there were baby gates and tethers permanently installed in cubicles and office doors, and the carpets showed signs of a pet-friendly history (hey, they were moving out of the building soon). Best yet was the fact that almost every dog I met turned out to have been adopted from the P&G PHNC after he or she was retired from research duties. Cool.

Finally, we got back into cars and drove for a little under an hour to the PHNC. The 250-acre site where the research animals are kept is tucked behind a P&G extrusion (dry pet food) manufacturing plant. The facility has capacity for roughly 350 dogs and 350 cats.

Let’s See the Animals

One of the charges made by PETA about dogs at a contract laboratory in Missouri (which Iams hired for some research) was that there were dogs who were surgically de-barked (had their vocal cords severed) to make them less noisy. You have to read PETA’s website very carefully to ascertain that PETA did not allege that these debarked animals were Iams research animals. Nevertheless, I was immediately suspicious when the first group of Beagles we passed by in their outdoor runs failed to start barking at our little tour group. When I realized they were neither barking nor making the hoarse sound produced by debarked dogs, I actually stopped in my tracks and squinted hard (they were 100 feet or so away); were they wearing antibark shock collars? A colony of 20 or so Beagles, with only one or two barking? Something is wrong!

My guide for the tour, the manager of the PHNC, was patient. “Those are young dogs, who are still in training to enter the actual research program,” he explained. “Also, they are thoroughly habituated to the sight of people passing by their runs. They also receive lots of exercise, individual attention from staff, and enrichment in their environments, so they aren’t desperate for stimulation or interaction.”

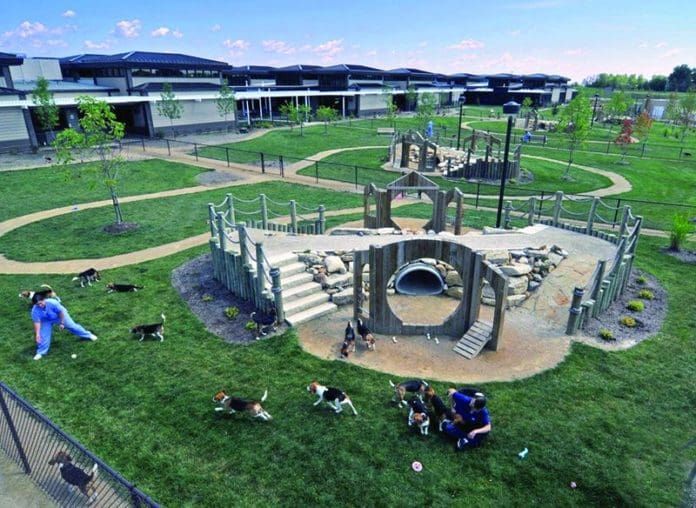

The PHNC is laid out a bit like a cross between a commercial farm and a university veterinary school campus, with a dozen or so buildings connected by paved paths and separated by grassy paddocks. The aroma of pet food is in the air, thanks to the nearby extrusion plant. Dogs are in view nearly everywhere, passing through dog doors into their outdoor runs, disappearing back into their indoor kennels, playing under the watchful eyes of attendants in one of several fenced “playgrounds,” or being walked on-leash by “animal welfare specialists,” as the staff members who care for the dogs and cats are called.

We passed through at least half of the buildings on the campus, viewing the indoor housing areas for dogs and cats, the clinical care rooms (where animals are taken for routine veterinary exams, blood draws, dental cleaning, and so on), as well as facilities where advanced veterinary research tools are located – things like strikeplate treadmills and high-speed cameras (to analyze changes in stride length, for example, in the maturing or aging dog) and body composition densitometers (an xray-like machine that can analyze an animal’s bone density as well as determine his percentages of body fat and muscle mass).

I was genuinely impressed with the thought and care taken with the housing for the animals. The indoor runs for the dogs are climate-controlled. When staff members noticed that a number of the long-term canine residents had neck or shoulder pain, P&G started researching dog doors that would swing open in such a way that the dogs didn’t have to muscle the doors aside with their necks or use a strained posture to pass through; they finally settled on doors that are split vertically down the center, like saloon doors in old Western movies. Dogs essentially pass straight through these doors, and the incidence of neck injuries dropped.

For the most part, the dogs are pair-housed with a compatible same-sex partner (though they have a daily opportunity to play in a larger social group). Each dog has a name (not just a number), and the front of each run has a whiteboard with notes about the dogs’ individual preferences or challenges. I saw notes like, “Cherry is blind, so talk to her before you touch her so she doesn’t get startled,” and “Pardner does not get along with Jake! Make sure they do not go to the playground together!”

The runs and indoor kennels were spotlessly clean, with staff members in constant attendance to clean up any poop or pee. The air-conditioning kept the indoor temperature comfortable, and I didn’t wrinkle my nose once; I never noticed an odoriferous room. All the dogs had raised beds and toys were present in every kennel. I didn’t see a single dog or cat pace with stereotypic distress or leap at its kennel or cage door for attention. All the animals seemed calm and well adjusted. And the handlers who were walking dogs outside all had clickers, and were using play with toys as rewards.

I know this is a dog magazine, but the cat housing facilities were equally impressive. The cats are kept in larger social groups in large, airy rooms with a ton of places to hide, climb, perch, and nap. All the cats have access to sun porches, a wealth of toys, and clean litter boxes.

Career Planning

Here is what I found most impressive of all: P&G plans each animal’s career from the time it is born to the time it will be retired from research; each animal is then admitted to an adoption program dedicated to placing retired research animals with P&G employees. (With about 2,300 P&G employees in nearby Mason, Ohio, and many thousands more in P&G’s Cincinnati headquarters, there is said to be a waiting list for the well trained, well socialized retired research dogs and cats.)

Dogs are typically retired at age 6, and cats at age 8, although a small senior population in support of research into P&G life-stage diets. In addition, “There are a few dogs and cats who will retire with us for their natural lives, as they aren’t suitable for adoption due to either behavioral or medical conditions,” explains Jason Taylor, manager of external relations for P&G Pet Care. These animals will also continue to test (consume!) senior diets – a sort of working retirement.

Puppies and kittens born into the P&G research program are extensively handled and socialized in preparation for their emergent careers. “We begin preparing our dogs and cats for adoption the moment they come to us,” says Taylor. “We do this by working with them at an early age – in puppy and kittenhood – to acclimate them to both home and kennel environments. New puppies are initially introduced to cars and vans, a variety of off-campus home environments, selected parks, and many new people, in order to support early cognitive development. Our training team and staff work hard at familiarizing every animal to common household items in our spacious Home Environment Room and by continuing their training in general obedience and manners throughout their lives. Dedicated ‘animal welfare specialists’ socialize, exercise, and groom them daily.”

P&G breeds some of the animals currently used in its research program and buys some from commercial breeders. I saw a variety of dog breeds, including the ubiquitous laboratory Beagles, as well as Golden Retrievers and Greyhounds.

P&G also conducts “in-home” palatability, taste preference, and clinical studies through the recruitment of dog owners via their veterinarians. According to Taylor, “More than 70 percent of the animals participating in our studies are pets living in private homes or pets from organizations where animals already live (such as service dog organizations).” And of course, all of the animal nutrition research conducted or overseen by P&G adheres to the company’s animal study policy.

P&G maintains a facility in Cincinnati, called the Winton Hill Discovery Center, as a “headquarters” for pet owners and pets participating in in-home studies. The Center offers pet owners the ability to drop off biological samples, pick up food, and discuss concerns with the animal care technicians and veterinarians. P&G Pet Care also hosts consumer research studies with pet owners at the Winton Center.

P&G’s Other Facilities

When P&G acquired Natura Pet Products in early 2010, a small-scale animal nutrition research facility in Fremont, Nebraska, adjacent to the Natura dry food production plant, was part of the package. I toured the production plant and research facility years before the P&G purchase, in November 2005. At that time, the research facility housed maybe 30 or so mixed-breed dogs (I didn’t look at the cat facilities), who were used in informal palatability and taste preference studies.

Today, the facility is known as the Fremont Health & Nutrition Center, and has the capacity to serve 30 dog and 30 cat residents. According to Taylor, “The Center is an extension of the PHNC, and follows the same P&G Pet Care animal studies policies. Studies taking place at the Center include palatability, digestibility, and bioassay studies. Every detail at the Nebraska Center is focused on the pets who live there, including oversized indoor and outdoor runs with large outside play yards, substantial ventilation systems for climate control, home-like environment settings with social rooms, regular and frequent daily exercise with animal care technicians and routine top-notch veterinary care.”

P&G does not conduct studies involving dogs and cats in any locations other than the three (Ohio, Nebraska, and in-home studies) mentioned above.

Hill’s Pet Nutrition

Even as I toured the P&G PHNC campus three years ago, I wondered how it compared with other pet food research facilities. I was particularly curious about Hill’s Pet Nutrition; nutritional research is the signature characteristic of the company that makes Science Diet and Prescription Diet pet foods.

So I was particularly pleased when I was contacted by a public relations person for Hill’s just a couple of months ago, and invited (along with a bunch of other journalists and bloggers with an interest in pet food) to tour the facility where Hill’s Pet Nutrition conducts its dog and cat food research and development work, the Hill’s Pet Nutrition Center in Topeka, Kansas. I negotiated a bit and pressed to see whether I could also tour some of Hill’s pet food production facilities in the area, and this was soon arranged.

Like P&G, Hill’s offered to pay for all of the invited journalists’ airfare and hotel accommodations and arrange for meals and transportation. As always, WDJ’s publisher paid my way instead.

A shuttle bus took us to the 170-acre Hill’s Pet Nutrition Center (PNC). We reorganized ourselves in a conference room, and were introduced to a number of Hill’s executives, including Kostas Kontopanos, the President of Hill’s USA since 2011; and Neil Thompson, President and CEO of Hill’s Pet Nutrition since 2009.

Hill’s is a $2.2 billion, global subsidiary of Colgate-Palmolive, and is headquartered in Topeka. The Hill’s product line includes more than 80 Prescription Diet brand pet foods and more than 90 Science Diet brand pet foods, which are sold in more than 90 countries. Hill’s employs more than 150 veterinarians, nutritionists, and food scientists to collaborate on its pet food product development and research.

Hill’s History

It wasn’t always so . . . global. Hill’s was founded by a veterinarian in New Jersey, Mark L. Morris, Sr., who developed his first canine diet in 1939 for a client, a blind man named Morris Frank, whose guide dog, Buddy, was suffering from kidney failure. Dr. Morris speculated that manipulating the dog’s diet could slow the progression of the kidney disease, and he began formulating and testing diets, with the help of his wife, in their home kitchen. They canned the food the old-fashioned way, in Ball jars. Mr. Frank and Buddy were touring the country, promoting and demonstrating Seeing Eye dogs, so Dr. Morris mailed the jars of food to Mr. Frank on his tour. After seeing some success with the diet, and having the jars break in transit, Dr. Morris bought a hand-operated canning machine and his staff canned the food.

Dr. Morris began studying various canine and feline diseases and formulating diets that would complement disease treatment. Throughout the 1940s, he developed diets for canine gastrointestinal disorders and obesity (it’s not new!). Eventually, Dr. Morris contracted a commercial cannery, the Hill Packing Company in Topeka, and licensed the company to produce his pet food formulas. He also gave the diet that he formulated for Buddy a formal name, Canine k/d.

In 1948, Dr. Morris established a charity for small animals that would later become known as the Morris Animal Foundation. The Foundation funds independent research into small animal disease to this day. Dr. Morris also established a research laboratory in Topeka in 1951.

In the 1950s, Hill Packing Company established canneries in six more states, and Dr. Morris continued to develop diets for treating sick animals. Eventually, Dr. Morris was joined in veterinary practice and then veterinary nutrition research and diet development by his son, Dr. Mark Morris, Jr. Their products were marketed under the name Hill’s Pet Nutrition. In 1968, Dr. Morris Jr. created the Science Diet line of pet foods for healthy pets. Dr. Morris Jr. also coauthored the first publication of Small Animal Nutrition, a clinical nutrition textbook, in 1983. The text has been updated many times and is used in veterinary colleges worldwide.

The Colgate-Palmolive Company bought Hill’s Pet Nutrition in 1976. Dr. Morris Sr. passed away in 1993 at the age of 92. Hill’s Pet Nutrition reached $1 billion in net sales in 2000. When Dr. Morris Jr. passed away in 2007 at the age of 72, he was still actively involved with Hill’s, and his presence is still strongly felt at the Hill’s Pet Nutrition Center.

Get to the Animals

Our tour guide of the Hill’s PNC was Scott Mickelsen, DVM, a Diplomate of the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine, and Manager of Pet Nutrition Resources for this campus (meaning he manages the animal colony). Four hundred and two dogs and 485 cats were reported to be living on the Hill’s PNC campus on the day of our tour – all of them kept according to the conditions laid out in Hill’s animal welfare policy (excerpted below and available in its entirety at tinyurl.com/hillspolicy).

The buildings that house the animals are all connected, with a total of 80,000 square feet of housing and treatment rooms, as well as kitchens and food preparation rooms. A 3,000 square foot veterinary hospital, where prophylactic care and urgent care (if needed) is provided, features everything you’d see in any modern veterinary hospital, including surgical suites and xray and ultrasound rooms. There are multiple rooms containing laboratory analysis equipment for blood and urine tests.

Unlike the P&G program, where the majority of research animals are retired from studies and adopted into homes, the animals at Hill’s typically live their entire natural lives on the Hill’s campus. They are adopted out of the program (almost always by a Hill’s employee) only if they develop a behavioral incapacity for the campus lifestyle. If they develop medical conditions, they are treated as thoroughly as any pet dog or cat at home as long as they have a good quality of life; if they need to be retired from participating in any studies as a result of treatment, they are – though they are likely to continue to be fed a Hill’s diet appropriate for their condition, and will continue to be monitored via blood and urine tests and physical examinations.

While dog lovers might be expected to admire the P&G model of retiring most of its research animals (at age 6 for dogs), and perhaps be critical of Hill’s for keeping almost all of its “pet partners” throughout their lifetimes, Hill’s points out that studying life-stage nutrition is critically important to the company. “A 13-year-old dog or cat may have different nutritional requirements than a 7-year-old dog or cat,” explains Dr. Mickelsen. “Disease frequency increases with age. If we adopted them out at 7 or 8 years, many of our foods designed to benefit older dogs and cats may not have been developed.”

The housing for the animals is provided in a series of wings, which are laid out in a repeating pattern; we could see all of the outdoor recreation areas for the dogs extending away from us into the distance. We were able to view the interior of one wing, representing one third of the total canine housing facility; we were told that the parts we didn’t see were identical to the parts we did view.

As one might guess in a nutritional research center, the feeding rooms function as the nerve centers of each wing. In the dog wings, four housing areas, each with a capacity of 20 dogs, are attached to each feeding room; a mirrored arrangement is located across a central hall that connects each of these wings.

The total capacity of the dog housing area is 480, but the actual numbers are usually less than that. The dogs eat their meals in a sort of stanchion; their food (including the amount they eat or decline to eat) is precisely recorded by scales that are built into the food bowl platform. (Entire conferences could probably be held to explain all the technology that has gone into the way the animals’ food is presented to them and recorded.) For the most part, they sleep in pairs in cubicles that line a large playroom; each group of 20 is released during the day into a large group room, outfitted with a plethora of toys.

Swinging dog doors keep the climate indoors comfortable, and allow the dogs to pass outside and recreate or snooze in a large outdoor play area.

The outdoor play areas are carpeted in artificial turf; a pergola shelters part of the area from weather and heat, although an uncovered area is available to them, if they prefer. Toys abound outside, too, and handlers are constantly present, playing with and petting the dogs – and cleaning up after the dogs – as you’d see in any good dog daycare facility. On the day of our tour, the animal care staff (for the dogs and cats) was said to consist of 55 employees.

The toys are rotated as a set a couple of times a week, both so they can be cleaned and to provide novelty when they are reintroduced. To prevent disputes over “favorite” toys, all the toys that are put out at any given time are the same kind.

All of the outdoor runs are connected by gates to much larger dog park-type facilities. Each group of dogs is allowed out for play in one of these large areas at different times of day.

Most of the dogs we saw were Beagles; historically, the dog of choice for laboratory research (because Beagles are almost always content when living in a pack). However, Hill’s is slowly integrating other breeds (including mixed-breeds) into its research colonies, but only at the rate that the senior animals pass away, so it might take a decade or more to see a non-Beagle majority on campus.

Each animal is microchipped, and computers located in the lobby area of the feeding rooms can identify each animal, show photographs of him or her for identification purposes (for new employees, mostly), and display his or her complete health history, information on the dog’s participation in studies, and of course, current diet.

All of the dogs we saw looked comfortable and well adjusted. As at the P&G site, I was surprised when groups of dogs playing in the Hill’s “Bark Parks” or in their outdoor runs failed to react in any way to the sight of our group passing by. I observed none of the stereotypic stress behaviors that are so common in shelter dogs or commercial breeding operations -although I did see one Beagle make a large, gloppy poop, and another immediately start to consume the poop (but that can happen anywhere with any breed, though most of us dog journalist witnesses remarked, “Ugh! Beagles!”).

The group housing rooms for cats are appointed like cat palaces – so many scratching posts, beds, hammocks, platforms, skywalks, toys, and tunnels. The cats in each group room have access to “sun porches” via tunnels – and the tunnels all have openings into alternate tunnels, in case a cat wants to get to the porch and another cat is blocking the way. (Look, that’s how cats are.)

We saw the entire cat housing area, encompassing some 60 separate rooms. The majority of the cats are housed in groups of 8 to 12 cats per room, although we saw some cats in individual housing units – referred to as “kitty condos.” These individual spaces are about 150 cubic feet of space (a little bigger than 5 feet by 5 feet by 5 feet) with multiple climbing perches and windows, including a bay window that allows the cats a panoramic view of their environment. These spaces are also individually ventilated.

According to Dr. Mickelsen, cats are housed individually for one of three reasons: “First, we have about 7 or 8 cats who are not behaviorally comfortable in a group housing setting, period. So they get their own housing. Second, in some studies, we need to collect biological samples, such as stool or urine, for a short period of time, so those cats will be individually housed for short periods. Third, cats with medical conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, might be individually housed so we can monitor every occurrence of elimination.”

Dr. Mickelsen pointed out that all the individually housed cats have the opportunity daily to enjoy themselves in large playrooms, and have daily access to the sun porches, just not 24/7 like the group housed cats.

We also saw one room that was decorated with several comfortable couches, chairs, and desks and contained no cats; we were told that it was a lounge that can be used by Hill’s employees from anywhere on the campus. The lounge is equipped with Wi-Fi, and cats can be “checked out” by the employees who need a cat break. (Employees can also check out a dog and take him or her for a walk or jog around the Hill’s campus.)

One of the innovations used by Hill’s to conduct metabolic studies (in which all urine and stool needs to be collected) or any study that requires the collection of all the animal’s urine, is the use of nonabsorbent beads in litter boxes, and other innovations for collecting dog urine (in old-fashioned labs, the test animal is required to live for a short time in a cage with a slatted floor, so that all the urine and feces can be collected in a pan underneath the cage. “We haven’t used cages with slatted floors for years,” says Dr. Mickelsen. “We devise things as needed. We found once that we had a hard plastic ball in the kennels that the dogs never played with, but were always urinating on. So we put that ball in the middle of a tray, like a lunch tray, and found that the dogs would urinate on the ball and we could capture all the urine in the tray.”

Types of Tests

According to Dr. Mickelsen, at any given time, about 50 percent of the dogs on the Hill’s PNC campus are participating in palatability or taste preference studies of some kind. In these studies, the dogs are given two or four foods to choose from, and allowed to make a choice of which to eat. A lot of technology goes into preventing them from overeating, however; the food bowls are on scales in a sort of little cubby. After the scales detect that an appropriate amount of food is consumed, the dog is warned (with an automated tone) to stop eating so that the bowls can be removed. Though most dogs heed the warning tone, if one doesn’t, a puff of air is blown into his face until he backs up, at which point the apparatus detects that he is safely out of the way and the doors to the cubby close.

The next largest group of dogs – about 30 to 40 percent of the population – are participating in “ad hoc” studies, typically designed to gather data or research an issue in support of the development of new products or formula changes.

Dogs participating in some sort of AAFCO feeding trial make up the smallest percentage of the canine research population at any given time, perhaps just 10 percent.

Which dogs go into which studies? Dr. Mickelsen describes this as an ever-changing puzzle. “We try to be as efficient as we can be, given the population. Some dogs are generalists, but we’ve trained some for specific tasks, such as urinating in a special setting or picking out different aromas, and those dogs tend to get assigned repeatedly to studies that require those skills. It takes several months to train dogs to detect certain aromas, for example, and to validate their abilities; it doesn’t make sense to pull that dog away from that work.”

Dogs who develop disease are treated for their conditions, and might be assigned to a study of diets that address their condition. For example, if a dog develops kidney disease, he would likely be placed on a diet of k/d, and his blood and urine samples used in tests in support of the ongoing refinement of kidney diets.

However, the bulk of Hill’s research on diets for animals with medical conditions does not happen at the Hill’s PNC; it happens in people’s homes. The company partners with veterinarians in practice and with vet schools all over North America, “recruiting” a pool of patients through their vets. “For example, when we developed j/d, we had some dogs with arthritis on our campus, but not in large enough numbers to do a big clinical study. By partnering with veterinarians, we can find many more patients to participate in these studies.”

Hill’s declines to state exactly how many pets might be participating in Hill’s clinical trials of diets at any given time (this is considered proprietary information), but Dr. Mickelsen would say that “the number of pets we touch outside of our facility is far larger than the number we have here.” In a trial of this kind, typically the owner and veterinarian both are “blinded” to the food, which is sent to them in a plain wrapper. The veterinarian takes any biologic samples needed (blood, urine, stool) and sends them to Hill’s labs, and also performs whatever physical exams and evaluations Hill’s asks for.

Ordinary dogs and owners also participate in palatability studies conducted by Hill’s. Of course, neither these dogs nor their handlers are specially trained for these tests, but the data they provide (in terms of their preferences) are used to validate and cross-check the Hill’s PNC findings in “real world” environments.

I asked Dr. Mickelsen if he had anything else he wanted WDJ to know about the Hill’s animal research. He said, “I would like people to know that we are genuinely passionate about the health and welfare of our animals, and we treat them like we would treat our own pets at home. When an old dog or cat gets sick, and we have to make a decision about his quality of life – that’s always a tough day for the people who have been caring for that animal for a long time. Those are the challenging days. And we are lucky to work for a company that shares the passion for animal health and welfare that our customers possess.”

In Contrast

There are a few other large pet food companies that conduct research on this sort of scale – Purina and Royal Canin, for example – but it has to be noted that few, if any, of the manufacturers of the foods on WDJ’s “approved foods” lists invest this much in either feeding trials or nutritional research.

Most (if not all) small-scale pet food companies conduct informal palatability and digestibility studies, on small numbers of dogs belonging to employees, local shelters, or breeders. Others may employ the services of a contract laboratory to feed the product to a population of dogs and record the results. The latter is an expensive step, and a tad risky from a public relations standpoint – remember that undercover video footage? In today’s competitive market – and with the white-hot, blazing speed of social networks – an undercover video of mistreatment of dogs or cats in a research lab could really damage a pet food company’s reputation and sales. A company executive better have solid faith and evidence that the contract lab takes the provision of animal welfare as seriously as a funeral.

While we’re sure that a pet food company executive could gain access to a contract lab to verify conditions and the quality of life for the resident test dogs and cats, it’s pretty difficult for anyone else to do so. Summit Ridge Farms, located in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania, is perhaps the highest profile and largest contract lab in operation in the U.S. that does feeding trials for pet food companies. The company routinely takes out full page ads in pet food industry magazines, describing its animal welfare and enrichment programs and picturing its “puppy parks” and “feline community living.” But the company strictly restricts access to the facility, and though I haven’t bothered in recent years, when I did try to contact the lab to discuss the possibility of a tour, my calls and emails went unreturned.

If it’s so expensive (and a potential public relations risk) to use contract labs to conduct a feeding trial, why not just skip this step? Even well manufactured products made of good ingredients and formulated to meet the AAFCO nutrient levels for a “complete and balanced” designation can turn out to cause digestive issues when fed to real dogs! You’d hate for your new product to hit the market and hear about dogs with killer gas or dangerous diarrhea. Feeding trials are a valuable source of critical information for pet food companies. It would be nice if the entire industry was doing them as thoughtfully and with as much attention paid to the quality of the animal subjects’ lives as Hill’s and P&G.