A DOG’S ADRENAL GLANDS: OVERVIEW

1. If symptoms such as hair loss, lethargy, weight loss, and sudden onset of excessive thirst and urination are seen, get the dog to your vet ASAP.

2. Avoid giving your dog corticosteroids for chronic conditions or long-term use. Steroidal drugs are a prime cause of Cushing’s disease.

3. Give licorice root to any dog with Addison’s disease or adrenal fatigue. The herb’s activity actually helps balance the adrenals.

The adrenals are small glands located just forward of the kidneys. They are so small, in fact, they were virtually ignored by early anatomists for centuries. Although small in size, they are extremely important in the overall hormonal balance of the body and its ability to maintain homeostasis.

The adrenal glands also interact with the hypothalamus and pituitary gland; the collaboration of the three glands is known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis). Their joint activities help control the body’s reactions to stress, whether it is physical or psychological. They also help regulate body processes such as digestion, the immune system, and energy usage.

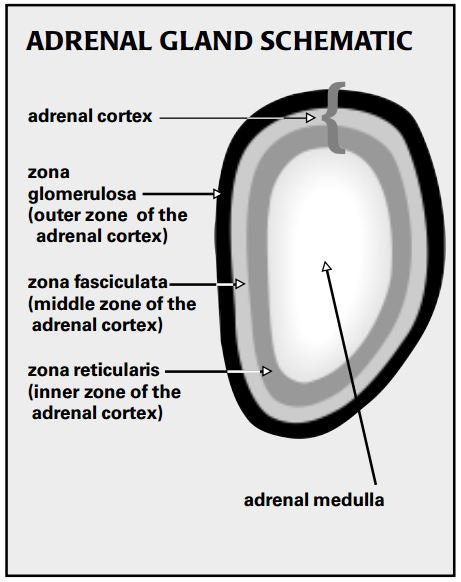

The adrenals consist of two distinct parts: the outer cortex and the inner medulla. These two areas are entirely different in their function, their cellular structure, and their embryological origin, so it’s odd (at least in terms of our current understanding of the complex gland) that they are “built” into the same structure.

Adrenal Medulla

The center of the adrenal gland, the adrenal medulla, produces two important hormones that are secreted in times of acute and severe stress, in what is known as the “fight or flight” mechanism.

The first, epinephrine (commonly known as adrenaline), plays a central role in short-term stress reactions. It increases the heart rate and force of heart contractions, facilitates blood flow to the muscles and brain, decreases stomach and intestinal activity, and helps with conversion of glycogen to glucose in the liver – all actions that would promote a lifesaving fight or flight.

The second hormone produced by the adrenal medulla is norepinephrine, also known as noradrenaline. Norepinephrine’s primary action is to increase blood pressure.

Adrenal Cortex

Whereas a dog could survive the surgical excision of his adrenal medulla, the adrenal cortex is essential to life. The cortex is divided into three layers or zones. The zona glomerulosa, the outer zone, is responsible for the secretion of mineralocorticoid hormones. The zona fasciculata, the middle and largest zone (about 70 percent of the cortex), is composed of cells that secrete the glucocorticoid hormones. The zona reticularis, the inner zone, is responsible for secretion of sex hormones.

The secretions of the adrenal cortex (and the commercially available drugs that mimic them) are often lumped into one category – corticosteroids, or simply, steroids – but they perform separate functions.

The mineralocorticoids (from the outer, zona glomerulosa) comprise a small portion of the overall mix of corticosteroids in the body, but play an important role. Their principle effect is on the transport of important ions such as sodium and potassium across cell walls. Aldosterone is the most potent mineralocorticoid, and is responsible for accelerating the secretion of potassium and retention of sodium from the tubules of the kidney, which in turn helps maintain the body’s water balance by increasing resorption of water. Sweat glands are also under the control of the ion-pumping action of mineralocorticoids.

A lack of mineralocorticoids ( Addison’s disease) may result in a loss of sodium and retention of potassium, a condition that, in its extreme, may prove to be fatal.

The zona fasciculata, or middle zone of the cortex, secretes two glucocorticoid hormones: cortisol and corticosterone. The glucocorticoids have a wide range of physiological activity in the body, whether they are present as natural hormones or as commercially produced drugs. As prescribed drugs, they are used for a wide variety of diseases and conditions – and are the most overused and abused drugs in the conventional veterinarian’s pharmacy. Most holistic vets, on the other hand, try to limit prescribing of glucocorticoids to an absolute minimum.

Glucocorticoids have an especially profound impact on the immune system and the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. The metabolic action of the glucocorticoids is to enhance the production of glucose (the body’s primary energy sugar from digestion), which results in a tendency toward hyperglycemia (increased blood sugar levels). In addition, glucocorticoids decrease fat production and increase the breakdown of fatty tissues, which results in the release of glycerol and fatty acids, readily available sources of energy.

Glucocorticoids suppress both inflammatory and immunologic responses. By suppressing inflammation, they may inhibit tissue destruction and fibroplasia (scarring). However, glucocorticoids also reduce resistance to bacteria, viruses, and fungi, which in turn favors the spread of infection. And they have a profoundly negative effect on healing.

The third type of hormones originating from the adrenal cortex are the adrenal sex hormones. Secreted in relatively small amounts by the zona reticularis (inner zone of the adrenal cortex), these include progesterone, estrogens, and androgens. The effect of the adrenal sex hormones is usually masked by the hormones from the testes and ovaries, but may take on more significance in the spayed or neutered animal.

Synergistic Steroids

As I just explained, all the adrenal “steroids” have specific functions. Complicating the picture is the fact that they also perform some overlapping functions. Their activities are all-pervasive, affecting a multitude of organs in a complex manner. What’s more, dogs may have a wide range of responses to steroids, depending on a number of factors. Practitioners can only guess what any individual dog’s response will be to any dose of steroid they choose to prescribe.

This means that any steroidal drug that is prescribed by a veterinarian with the intention of having one effect may well have other unpredictable and unwanted effects. This is why drugs that are supposedly strictly glucocorticoid in action may well cause a dog to experience excessive thirst and urination (a mineralocorticoid-effect). Because of the functional overlap of these steroids, there is no way to separate their beneficial effects from their potentially harmful ones, no matter how hard the drug companies try to convince us otherwise.

Let’s say, to give an example, that you have chosen to treat your dog’s skin condition with a prescribed steroidal product (likely a glucocorticoid), because it has potent activity as an anti-inflammatory agent. Unfortunately, that same steroid will have an adverse effect on the immune system, slowing your dog’s normal immune response and retarding healing. He may also experience increased thirst and urination.

In addition, glucocorticoid hormones (either naturally produced or from prescribed medications) stimulate the adrenal medulla. There are several potential results of this low-level adrenal stimulation: the increased load on the heart may cause heart failure; the chronic excess blood glucose may lead to diabetes mellitus; and the persistent stimulation of the adrenals may lead to “adrenal fatigue” or ultimately to adrenal failure (Addison’s disease).

Diseases of the Adrenals

There are two major diseases of the adrenal glands. One involves a hypersecretion of the hormones of the gland (Cushing’s disease, or hyperadrenocorticism). The other, Addison’s disease or hypoadreno-corticism, is the result of a hyposecretion.

Cushing’s Disease

Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s) may be the most frequent endocrinopathy in adult to aged dogs. The lesions and clinical signs associated with the disease result primarily from chronic excess of cortisol. Animals can exhibit any number of a wide variety of clinical signs, making proper diagnosis a challenge, even after evaluating a number of appropriate laboratory tests. The disease tends to be insidiously, slowly progressive.

There are three primary ways in-creased cortisol levels can create a “Cushinoid” reaction in dogs: tumors of the pituitary, functional tumors of the adrenals, and long-term administration of cortico-steroids.

Pituitary tumors affect the adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) -containing cells of the pituitary; this form of the disease is referred to as pituitary-dependent hyperadreno-corticism. Functional adrenal tumors are a far less common cause of the disease in dogs; the ratio of pituitary-dependent to primary-adrenal disease is about 80 percent to 20 percent. Many of us in the veterinary business worry that the most common cause of Cushing’s is drug-induced – excessive corticosteroid therapy given over a prolonged period.

Clinical signs of Cushing’s, no matter its primary cause, may include one or most of the following:

• Polyuria (increased frequency of urination), polydipsia (increased thirst), and polyphagia (increased, ravenous hunger).

• Weakening and atrophy of the muscles of the extremities and abdomen, resulting in gradual abdominal enlargement, lordosis (sway back), muscle trembling, and weakness.

• Weight loss. While most dogs appear fat, they may actually lose weight due to the loss of muscle mass.

• Fat deposits in the liver, resulting in diminished liver function.

• Skin lesions are common and are often the most recognizable symptoms of the disease. The skin may thin, or mineral deposits may occur within the skin, especially along the dorsal midline. The dog may also exhibit hair loss in a non-itchy “hormonal pattern” (bilateral and symmetrical hair loss, not patchy as typically seen with allergies, and often associated with thinning of hair and poor regrowth, rather than a complete loss of hair). This hair loss may be concentrated over the body, groin, and flanks, and spare the head and extremities. In chronic hormonal conditions the hair thinning may be associated with a thickening and a black discoloration of the abdominal skin called acanthosis.

• Behavior changes: lethargy, sleep-wake cycle disturbances, panting, and decreased interaction with owners.

A tentative diagnosis may be inferred from the clinical signs, but positive diagnosis requires laboratory confirmation. Differentiating pituitary-dependent from primary-adrenal Cushing’s is impossible without lab tests.

Cushing’s syndrome due to the administration of corticosteroids is easy to diagnose by asking the question: “Is your dog being treated with corticosteroids?” This form of the disease is easy to treat by discontinuing the drug. Note that glucocorticoids come under many brand names, and each type of glucocorticoid drug supposedly has its own specific activities, potency (compared to naturally occurring hormones), onset and duration of action. Also, the mineralocorticoid potential of all of these are affected by the individual animals’ responses to the drug.

A recently described condition called “adrenal hyperplasia-like syndrome,” mimics Cushing’s in the way its symptoms appear, but is likely due to a congenital imbalance in either the dog’s growth hormone or its sex hormones. (All of this offers further evidence for the interconnectedness of all the adrenal/pituitary hormones.) To date this disease has been well defined in a line of Pomeranians, and has also occurred in Samoyeds, Chow Chows, toy Poodles, and Keeshonds.

In most cases, the dog’s clinical signs have led the practitioner to suspect Cushing’s, and initial testing may help to differentiate this from diseases that present in a similar fashion.

Almost any hormonal condition may produce skin lesions similar to the Cushinoid dog, and increased thirst and urination may be due to a variety of diseases such as diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, or renal failure. Also, normally aging animals may have many of the same symptoms as Cushing’s.

After other differential diagnoses have been ruled out, there are several tests available to help ascertain the cause of the syndrome – pituitary-related or adrenal. Your vet may need to run a series of tests to help understand the causal pathway of the disease.

For example, tests are available to evaluate the functional capability of the steroid-secreting cells of the adrenal, to evaluate the effect ACTH has on the secreting ability of the gland, and to measure plasma concentrations of circulating steroids and ACTH under certain conditions. Radiographs, ultrasound, or computerized tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be helpful.

The conventional medical treatment for Cushing’s is aimed at attempting to shut down the excess production of hormones. There are several drugs that are specific for destroying the functional capacity of the particular cells from the area of the pituitary or the zone of the adrenal that is affected. In some cases, surgery may be used to remove the affected cells.

In all cases, the drugs will be effective only against certain cell lines (thus the need to ascertain which cells are the culprits). Furthermore, all drugs that have been used to date have a wicked list of adverse side effects – user beware! Surgery is also a difficult option; cutting into the pituitary that lies on the base of the brain is not an operation for the novice, and tumors of the adrenal tend to be microscopic in size and scattered throughout the gland.

Addison’s Disease

Hypoadrenocorticism, better known as Addison’s disease, is uncommon in young to middle-aged dogs. Unlike Cushing’s, which is a more insidious and chronic disease, Addison’s can have rapid and fatal consequences.

Many of the ongoing symptoms of Addison’s disease are not specific; they are more into the category of the ADR patient (Ain’t Doing Right): slowly progressive loss of body condition, failure to respond to stress, and recurrent episodes of digestive problems (gastroenteritis). The dog may lose weight (often an excessive amount), urinate more frequently, refuse to eat, and suffer bouts of vomiting and/or diarrhea.

As the disease progresses, though, a lack of aldosterone, the principal mineralocorticoid, results in marked changes in blood serum levels of potassium, sodium, and chloride. These alterations in electrolytes may lead to an excess of serum potassium, which then causes a decrease in the dog’s heart rate (bradycardia), and this, in turn, predisposes to weakness or circulatory collapse after even light exercise. The diminished circulation may be severe enough to trigger renal failure.

The condition may progress to complete failure (true Addison’s syndrome), and the dog may collapse. Without treatment, these dogs may die.

Diagnosis is often presumed from the dog’s history and clinical signs, and laboratory results may be used to confirm the condition. Changes may be seen in the blood picture, electrocardiogram (ECG), and sodium:potassium ratio.

An adrenal crisis is an acute medical emergency. The dog will need fluids, emergency doses of glucose and perhaps glucocorticoids, and supportive immediate therapy. Long-term therapy will likely be indicated; you need to consult with your holistic vet for alternatives to the corticoid drugs that will likely be recommended by a conventional vet.

The Pituitary Gland Connection

The pituitary gland is mentioned here because it is a prime regulator of adrenal secretions, as well as providing regulatory functions for many other endocrine glands.

The pituitary is a very small endocrine gland located on the underside of the brain. It is attached to the hypothalamus, a portion of the brain that collects and integrates information from all parts of the body, which is then used to regulate the secretion of hormones produced in the pituitary.

For such a small gland, the pituitary secretes a veritable plethora of hormones, many of which are the prime instigators/initiators for the secretion of other hormones from endocrine glands located in other areas of the body. It is almost as if the pituitary is the on/off switch for many of the body’s hormones.

While the connections between the pituitary and the adrenals are directly evident, the adrenals and their secretions are also secondarily involved in many other glands and functions of the body. For example, DHEA, an androgenic hormone produced by the adrenals, may be involved with obesity and aging. And the functioning capabilities of the thyroid may be indirectly linked to adrenal function. And let’s not forget that all forms of hormones, including those produced by the adrenals, act in the central nervous system as neurotransmitters or neuromodulators – further evidence for the importance of the mind/body link.

Other Adrenal Diseases

Diseases of the inner zone of the cortex, the zona reticularis, are relatively rare. They are generally associated with neoplasia (tumors) and as a rule they create an excess secretion of hormones associated with the specific cells involved with the tumor. Depending on which steroid is secreted in excess, the dog’s sex, and his or her age at onset, the affected animal may exhibit virilism (the development of masculine traits in the female), precocious sexual development, or feminization.

Because the primary hormones secreted by the adrenal medulla (epinephrine and norepinephrine) are related to stress, its primary disease is usually related to a chronic overstimulation, which in turn might create adrenal fatigue and/or lead to other conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or heart failure. One type of tumor of the medulla, the pheochromocytoma, while uncommon, has been occasionally reported. Because the tumor increases the secretion of hormones, its symptoms include increased heart rate, edema, and an enlarged heart.

Alternative Therapies for Conditions of the Adrenals

It should be obvious from the discussion of the adrenals that they are an integral part of a complex of interacting organ systems, all with independent, but overlapping functions. Put all this together and you’ve got a real challenge for trying to select the best therapeutic regime. On the other hand, since they typically work with entire body systems, alternative medicines may offer the best approach to overall and long-term healing.

Note that an Addisonian crisis (see above) is a medical emergency and requires immediate veterinary attention.

A general approach to treatment for either Cushing’s (hyperadrenocorticism) or adrenal fatigue (hypoadrenocorticism) might include the following:

• Discontinue chronic use of glucocorticoids if at all possible. The number one cause of Cushing’s syndrome in dogs is the prolonged use of corticosteroids. Find a good holistic vet to help you slowly wean your dog from steroidal drugs.

• Proper nutrition. Use of a fresh, healthy, balanced diet will assure proper organ system functioning. Natural, fresh foods won’t contain toxins that compromise the functions of organs.

• Minimize life’s stressors. Important components include proper exercise, correct weight for the breed, socialized behavior to live at ease with humans and other animals, and a well-defined place in the hierarchy of the family’s relationship. Most of all, let your dog be a dog.

• Minimize exposure to toxins. Plastics, pesticides, and herbicides have been shown to affect sex hormones. Preservatives and other artificial additives in foods and vaccines may adversely affect hormonal output.

• When indicated, use whole-body therapies. Acupuncture and homeopathy are examples of techniques that, when used properly, offer balance to the whole body.

• Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) is specific for the adrenal glands, especially for fortifying them after Addison’s or adrenal fatigue. Since the herb’s activity actually helps balance the adrenals (as well as most other organ systems), I often recommend it for any condition that might stress those glands. Check with a qualified herbalist for dosages and best uses of the herb.

• Finally, avoid the temptation to “chase symptoms.” Conventional medicine is notorious for “take-a-shot-and-run” treatments that address current symptoms and do little for the long-term health of the individual. With diseases of an organ system as complex as the adrenals, this approach may be satisfying for the short term, but may never result in a complete resolution of the disease. Have your holistic vet come up with a long-range plan of action that both of you are comfortable with, and follow the plan until you see some results.

Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.

How much licorice Root should I give to my 13 lb Chihuahua who needs help desperately- DIAGNOSIS: Cushings- but off the charts- Vetoryl 2 caps ever 12 hrs 10 mil isn’t working- Pls help- she is going down hill fast-😢

its sad that you never got a reply to your question.. I hope your do is okay