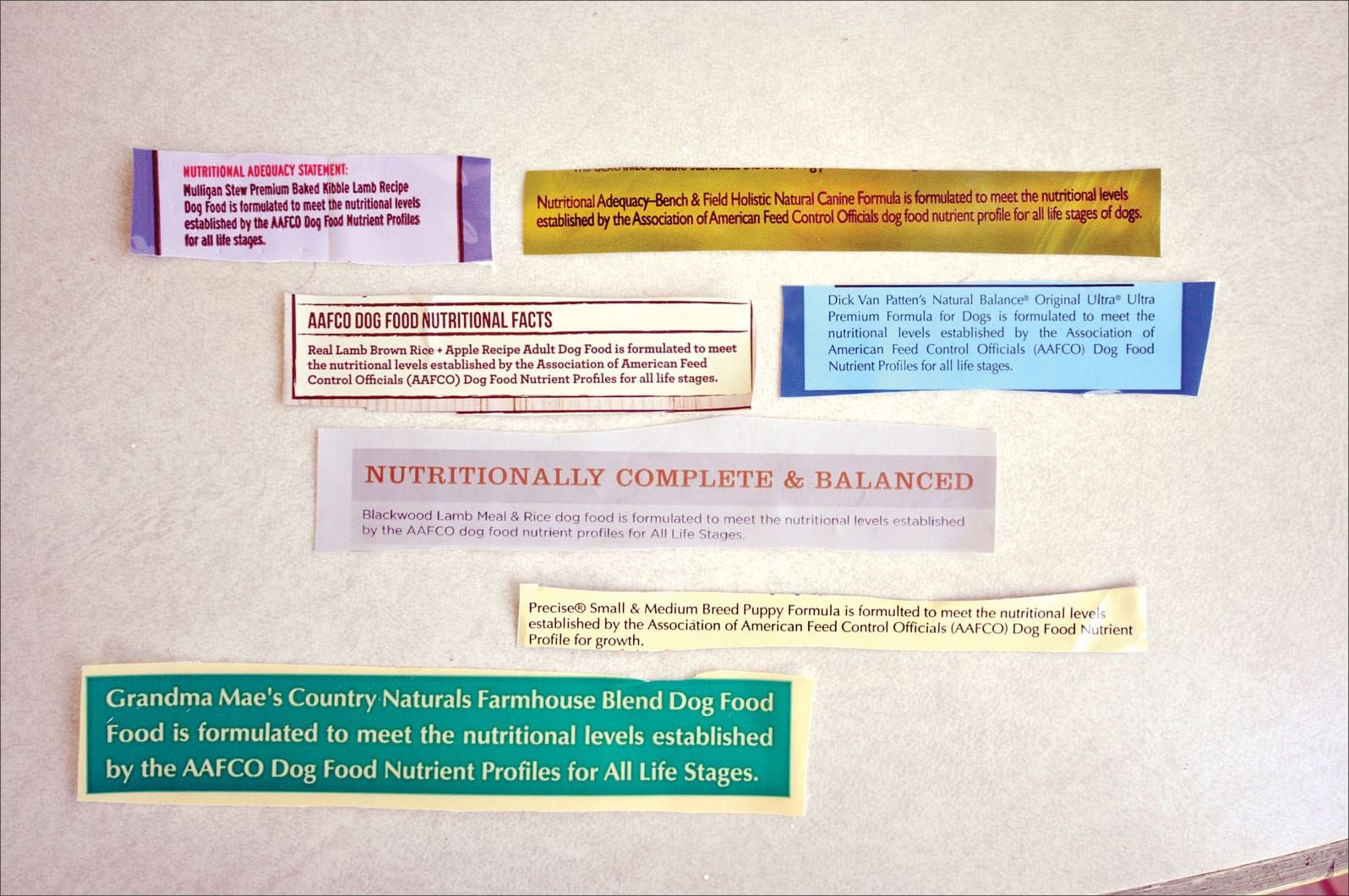

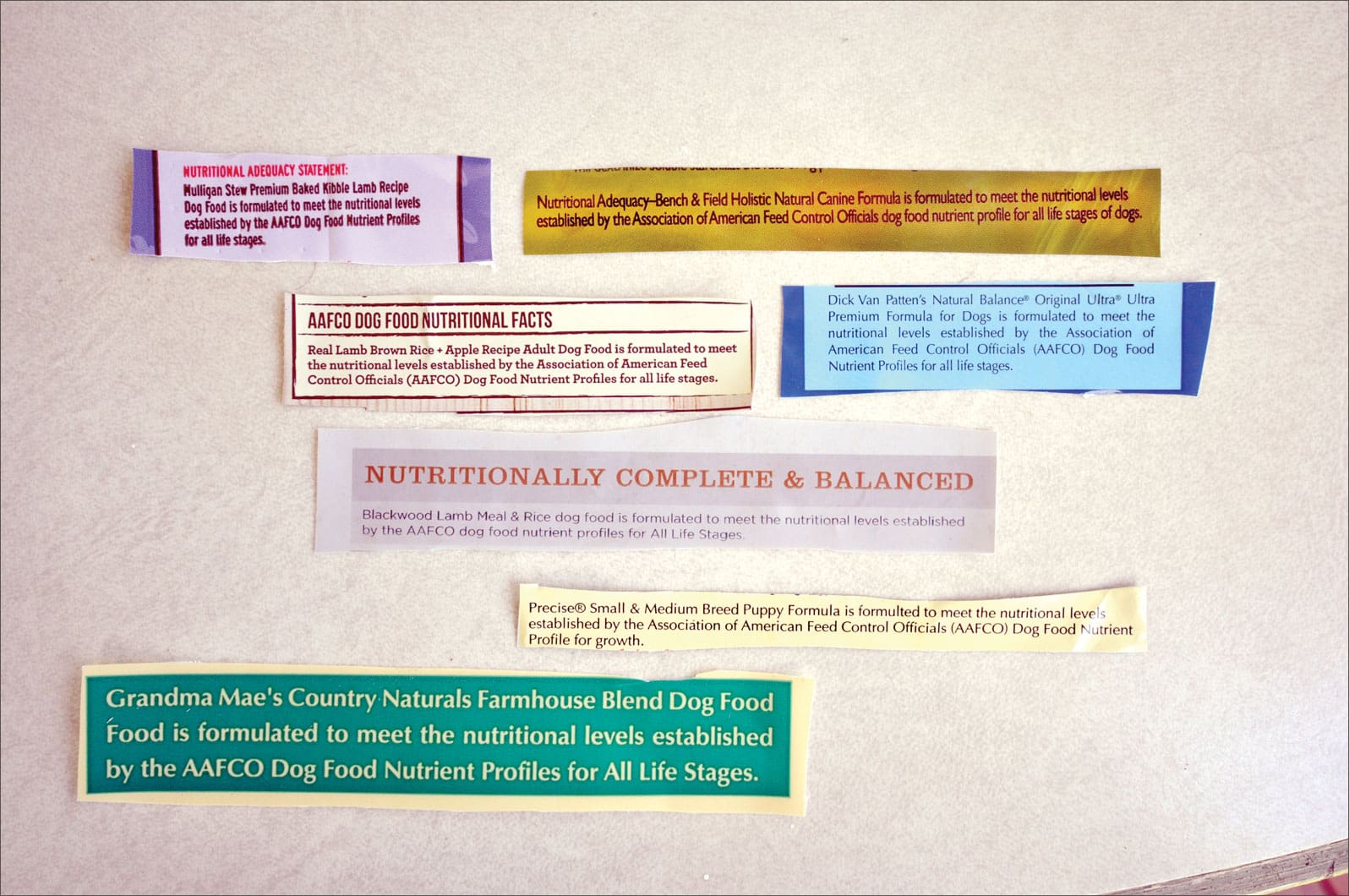

When buying food for their dogs, owners depend on the product manufacturers to deliver a “complete and balanced” diet in those bags, cans, and frozen packages. Perhaps without even being aware of it, owners also understand that there are government agencies responsible for setting standards as to what constitutes a “complete and balanced diet” for dogs, and for making sure that pet food makers meet those standards. We count on manufacturers and regulators alike to “get it right” so we can feel confident that our pets are getting everything they need, in just the right amounts.

288

So, it’s a bit disconcerting to learn that the three most important players in the setting of those nutritional standards have made changes to the nutrient lists and nutrient levels in recent years – and that each organization’s recommended nutrient “profiles” or “guidelines” differ from the others in some significant ways.

The Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) is the arbiter of American pet food’s “nutrient profiles” – a table of all the vitamins, minerals, protein and its constituent amino acids, and fat and its constituent fatty acids that are needed (and a minimum amount or acceptable range for each nutrient).

AAFCO’s ingredient definitions and nutritional guidelines are developed with substantial input from the pet food industry, such as the Pet Food Institute (PFI, a lobbying organization for pet food companies), American Feed Industry Association, National Grain and Feed Association, and the National Renderers Association. Academia plays a role, too, as lots of nutrition research (often funded by pet food companies) is conducted at universities with agricultural and/or veterinary departments. Industry representatives are non-voting advisors to the committees who set the standards. AAFCO itself has no regulatory authority; it’s up to states to adopt and enforce the AAFCO model regulations of feed ingredients and nutrient guidelines as laws.

Historically, to build its “Dog and Cat Food Nutrient Profiles,” AAFCO relied heavily on guidelines created by the National Research Council (NRC), a branch of the National Academies. (Scientists are elected to the National Academies to serve as independent advisers on scientific matters. The Academies do not receive direct appropriations from the federal government, although many of their activities are mandated and funded by Congress and federal agencies.)

The NRC substantially revised and updated its “Nutrient Requirements for Dogs and Cats” in 2006; the previous version was published in 1985.

AAFCO has been revising its own guidelines, and expects to publish the updated “Dog and Cat Food Nutrient Profiles” in 2014, presumably with a grace period before companies must comply with the changes. Additional changes scheduled to be put in place around the same time include requiring all pet food labels to provide information on calories, and adding new minimum requirements for omega-3 fatty acids for growth and reproduction.

A European group analogous to AAFCO, called the European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF), published its own revised guidelines in 2012. (The FEDIAF regulations are important to U.S. pet food companies, since many manufacture foods that are sold in both the U.S. and Europe.)

Both AAFCO and FEDIAF relied at least in part on the NRC guidelines, yet there are substantial differences between the three groups’ recommendations.

Pet foods sold in the U.S. that display “complete and balanced” on their labels must meet AAFCO requirements, while those that are also sold in Europe must meet AAFCO and FEDIAF guidelines. Exceptions are made for foods that use feeding trials to prove nutritional adequacy, or meet product family criteria (where foods that are substantially similar to another food made by the same company do not have to be separately tested). There is no requirement that any foods comply with NRC recommendations.

Comparison Difficulties

It’s not easy to compare nutritional guidelines between these three organizations. For starters, nutrient requirements can be presented in three different ways:

– As a percentage of food on a dry matter (DM) basis. This value is complicated by the assumption that the food has a particular energy density.

– As an amount per 1,000 kilocalories (kcal, or what is commonly referred to as calories). NRC calculates nutrient values for calories based on the needs of a healthy, active dog, not the calories a dog actually consumes. A dog’s nutritional needs are not reduced when he consumes fewer calories as he gets older or slows down.

– As an amount per body weight of the dog. Body weight is computed to the ¾ power, a mathematical computation that accounts for the fact that large dogs eat less for their weight than small dogs do. That critical step, however, is often overlooked or ignored when people talk about nutrient requirements based on body weight. In addition, these guidelines should be applied to a dog’s ideal weight, not actual weight. An obese dog does not require more nutrition than a dog of proper weight, nor does a thin dog need less.

Each of these methods will produce the same results if the energy density is accounted for and the caloric requirement is calculated based on the ideal body weight of a healthy, active dog.

NRC provides nutrient guidelines presented in all three ways, while AAFCO and FEDIAF use only the first two methodologies. FEDIAF increases many NRC values by 20 percent to account for its assumption that pet dogs need fewer calories than what NRC calculates.

To make comparisons even more difficult, different units of measurement are used with some nutrients. For example, NRC shows vitamin A recommendations in RE (retinal equivalents), vitamin D in micrograms, and vitamin E in milligrams; AAFCO and FEDIAF both use international units (IU) for all three. Complicated conversions are required to compare the different units.

Additional differences arise between how life stages are grouped. NRC provides separate recommendations for growth (including subsections in some cases for puppies 4 to 14 weeks old, and those older than 14 weeks); adult dogs for maintenance; and late gestation and peak lactation (pregnancy and nursing). Further modifications are made based on the number and age of puppies during lactation. AAFCO and FEDIAF use just two categories, “adult maintenance” and “growth and reproduction,” grouping puppies and females who are pregnant or nursing together. Foods that meet the requirements for both groups can be classified as meeting the guidelines for “all life stages.”

Lastly, the target amounts for the nutritional guidelines can be expressed in several different ways. NRC uses the following categories, not all of which are provided for every nutrient:

– Minimal Requirement

– Adequate Intake

– Recommended Allowance

– Safe Upper Limit

The “recommended allowance” is not meant to be an ideal amount, but rather takes into account practical considerations of formulation and ingredients, and is therefore the most appropriate category to use for comparison to AAFCO and FEDIAF.

AAFCO provides only a recommended minimum amount, and, in many cases, a maximum amount. FEDIAF does the same, but also includes some maximums based on European laws. Surprisingly, NRC does not show a safe upper limit for most nutrients, including some that are known to be toxic in high amounts, such as zinc and iron.

When units per 1,000 kcal are compared between the three agencies, many of the recommendations are identical, and others are close enough that any differences are probably due to minor conversion and rounding discrepancies. This likely reflects both AAFCO’s and FEDIAF’s reliance on the NRC guidelines. But some values are markedly different.

Some discrepancies can be explained by the difference in life stage groupings. For example, AAFCO and FEDIAF may choose to use NRC’s recommended allowance for young puppies for their “growth and reproduction” category, even though NRC’s recommendations for lactating females may be higher.

Other cases are not readily explainable. NRC’s recommended protein amount for adult dogs, for example, is just 10 percent protein on a dry matter basis, which is extremely low. Fortunately, both AAFCO and FEDIAF use more moderate values, requiring a minimum of 18 percent protein (DM) for adult dogs.

Varying calcium levels are similarly inexplicable. NRC gives a single acceptable range of calcium per 1,000 kcal for growing puppies after weaning, while FEDIAF has different ranges for puppies before and after 14 weeks of age, plus separate categories for puppies in the older group, based on whether their anticipated adult weight is below or above 15 kg (33 pounds). The FEDIAF’s more comprehensive guidelines appear to reflect knowledge gained in the last two decades of how excess calcium causes bone and joint abnormalities in large breed puppies, who are especially vulnerable prior to the age of about six months, but that doesn’t explain why the NRC does not account for the greater risk of too much calcium in this group.

Ideally, pet foods would be formulated to meet the requirements for all three agencies, to ensure that foods provide at least the highest minimum value and do not exceed the lowest maximum value of the three for each nutrient. In addition, even though a food does not have to meet AAFCO guidelines if a feeding trial is done, it still should do so. Feeding trials are considered the “gold standard” by the industry, but in our opinion, they are not of long enough duration to reveal health problems caused by many nutritional inadequacies or excesses, especially for adult dogs. The use of feeding trials and the narrower range of nutrient guidelines agreed on by the three agencies provide the best guarantee that the diet you feed really is “complete and balanced.”

Mary Straus is the owner of DogAware.com. She lives with her Norwich Terrier, Ella, in the San Francisco Bay Area.