Most people, unwittingly or intentionally, use a lot of physical force when raising and training their dogs.

The purposeful ones have a whole variety of reasons. Some may have read about behavioral theories regarding dominance and “the importance of showing the dog who’s boss.” Fans of these theories may advocate imitations of canine behavior such as “scruff shakes” or “Alpha rolls” to convince the dog he’s at the bottom of the family hierarchy. Others may have been influenced by advocates of traditional, military-style training – think of yanking collar ‘corrections’ or using the leash leveraged under their foot to forcibly pull a dog into a Down. Still others may be practicing old-fashioned folk “wisdom” when they do things like push a puppy’s nose into a puddle of pee, or smack a rowdy pup with a rolled-up newspaper when he jumps up on the couch.

Then there are the people who aren’t intentionally or mindfully using force on the dog, but who end up doing just that in the course of struggling to get him to behave. My guess would be that this is the majority of dog owners, those of us who reflexively smack the dog for jumping up on our clean clothes, who don’t yet know the trick to walking the dog without his pulling our arms from their sockets, and who have seen hundreds of people using the “push the puppy’s bottom down while repeating SIT!” method of training.

The thing is, sometimes these methods work. So people – some people – keep using them.

However, I doubt that anyone would admit to enjoying inflicting discomfort, pain, or intimidation on his or her dog (and hey, if they did, they probably would read some other magazine!). I’m fairly sure that most of the people who “take a hand to” their dogs are unaware of all the consequences. And I’m absolutely certain that if they learned an easier, more enjoyable, and more effective way to get their dogs to do what they want them to do, most people would. And that’s where WDJ comes in!

The following are discussions with two trainers who use and advocate non-force training. Each has different reasons for wanting to avoid the use of compulsion-based training techniques, and different, compelling explanations for why they think that dog owners should employ positive training techniques. I learned a lot in my conversations with them, and I hope you will, too.

———-

Creating Dogs with Initiative and a Desire for Partnership

Nina Bondarenko is the program director for Canine Partners for Independence (CPI) in Hampshire, United Kingdom. A native of Australia, Bondarenko has trained dogs for show and competition, judged Schutzhund trials and breed suitability tests, and now lectures regularly on canine behavior, development, and cognition.

Bondarenko says her start in dog training in Australia was inadvertently oriented toward positive methods, “because I didn’t know better,” she jokes. She got her first Rottweiler when she was a young teenager. She trained him herself to the best of her abilities, and he went everywhere with her.

Eventually, Bondarenko became interested in more advanced training for her dog, and she sought the advice of some local dog experts, including an old man who lived nearby who raised “very ferocious crossbred dogs” that were used to hunt and kill kangaroos. Bondarenko says that when the old man, who had a slight build, would go into the kennels, sometimes the dogs would try to pin him against the wall, but he would quite confidently fend them off.

She says the sight was terrifying, but he explained to her that “you just have to show them you’re not scared of them. You don’t have to bash them or strangle them or kick them or anything, you just have to be completely confident around them – so that’s what I did with my dog.”

She also sought advice from the man’s wife, who took the leash of Bondarenko’s young dog and demonstrated some classic force-based obedience methods. “She told me, ‘See, you’ve just got to do this to him, you’ve got to make him do this.’ And she started flinging him around at the end of the leash. I said [in a tremulous voice], ‘Oh, whoa, he doesn’t know how to do that!’ and my poor dog was looking like [in a squeaky voice], ‘I need some help, what’s going on?’ He was trying to comply, but he didn’t know what hit him!”

Bondarenko says she took her dog home and thought about what she had seen. She decided, “Naw, I can’t do that. If he’s going to be my mate [pal] and go with me everywhere, I can’t do that.” Instead, she says she watched him play with other dogs and would try to mimic what other dogs did when they wanted to control each other. “For example, if he was doing something I didn’t like, I’d go menacingly still, and he’d get the message.” Probably because of her unwitting confidence, her good relationship with the dog, and because she never tried to force him to do things, her Rottweiler complied with her wishes without incident.

Bondarenko became a big fan of the breed, and even began breeding Rottweilers. However, as she pursued her interest, she says she was told numerous times by unappreciative Australians that “Rottweilers are stupid, stubborn, ugly, ignorant, untrainable, aggressive, and lazy.” Her experience with the dogs was quite different.

“I was training them just by guesswork, and they were lovely dogs; smart, eager to learn, affectionate, and loyal,” Bondarenko says. However, as she gained an interest in showing the dogs, she joined a training club, and with her new female dog, started learning about and using the traditional, force-based training methods that were in style at that time. In no time at all, she says, her dog “suddenly became stupid, stubborn, ugly, ignorant, untrainable, aggressive, and lazy!”

For example, the instructor would say, “Say ‘Heel’ and jerk the neck! Say ‘Heel’ and jerk the neck!” Bondarenko says it didn’t take long for her dog to start growling at her when she said “Heel!” because she knew to expect a jerk on the neck.

“The other thing was, if your dog broke the ‘Stay,’ you were supposed to let him come to you, then drag him back to position and throw him down . . . The first time I tried to do that, my dog went very rigid and tense. The second time I tried to do it, she was up and waiting for me – and she would have had me,” says Bondarenko. Even the instructor’s own dog discouraged Bondarenko’s interest in this style of training. “He had a little Corgi that used to attack everyone and had to be kept tied up, so this wasn’t a very encouraging example,” she laughs.

Force won’t work here

Bondarenko continued to pursue her interest in dog breeding and training, and studied animal behavior in college. Today, after 20-plus years of professional training and advanced studies, she says she has two main concerns about force-based training. First, there is a limit to what you can accomplish with force; it can be effectively used for stopping a behavior, but can’t be used to get dogs to offer behavior. Positive reinforcement training, on the other hand, is “absolutely brilliant” for getting a dog to take initiative and find every way possible to be helpful and responsive to his or her handler.

In her work at Canine Partners for Independence, Bondarenko developed what she calls a puppy education system where the selected puppies start “training” in the homes of volunteers at seven weeks. The handlers have been taught to use operant conditioning, whereby the puppies learn to solve problems and accomplish their goals – from finding the right place to go to the bathroom to pressing light switches – by offering behavior. They are rewarded for using their noses, mouths, and their feet to touch and manipulate objects, and taught that if they want attention and petting, they must offer some behavior.

By never winning rewards of any kind for the “wrong” behavior, and always getting what they want when they display the “right” behavior, Bondarenko says the puppies “grow up incredibly cooperative, compliant, and easy to train and motivate. When they do the right thing, it gets reinforced right away. And when they are wrong, nothing happens. This is absolutely non-threatening, and it makes sense to them,” Bondarenko describes. In other words, they are infinitely motivated to show initiative.

When the puppies are between 12 and 15 months old, they are returned to the CPI training center where Bondarenko and her trainers begin to teach them to refine the behaviors they have learned. For example, while a puppy may have learned to nudge a light switch with his nose, he is now taught to press it really distinctly, and perhaps three or four times. The third and final phase of training gets the dog and his new disabled partner used to each other. “Here, the dog has to learn again,” describes Bondarenko. “His new handler may speak very differently or move differently from his previous trainers. He may have to learn a new way of going through a door, or picking up crutches and getting them properly into the hands of his handler.”

Even after many years of working with assistance dogs, Bondarenko says she’s amazed and thrilled with the things that a positively trained and motivated dog can do for people. “Look, there’s no way you could force a dog to do these things,” she says. “Imagine an aversive trainer trying to get the dog to help with the laundry. How could he make the dog open the washing machine door? Will it work to smack the dog if he doesn’t do it? Not likely!”

Plus, as Bondarenko points out, even if physical corrections did work to make dogs do things, this solution could not be put into practice by many disabled people who currently enjoy an assistance dog partnership.

“Say the dog is going to be given to a thalidomide survivor whose arms are three inches long. What’s she going to do if the dog has been trained with pulling and smacking, and he doesn’t do something he is supposed to? ‘Watch out, dog, or I am going to look at you quite fiercely!’ No, assistance dogs can’t be forced to work. They have to be a willing partner, an enthusiastic participant in everything the person does.”

If, in contrast, the dog is punished when he offers a behavior and it is the wrong one, his mistrust of the handler and fear of using initiative will grow. Eventually the dog will avoid using any initiative at all – a behavior that is apt to result in his being labeled “stubborn” or “sulky.”

Fallout of force

Bondarenko’s second major concern with the reliance of force to control the dog has to do with the risk of pushing the dog into behaving in one of several undesirable ways. She explains:

“Everyone has heard the expression ‘fight or flight.’ In dog training, I suggest that there are four main behavioral responses that you are apt to see when a dog has been frightened or stressed: fight, flight, freeze, or fool around.

“A dog that is very self-confident will fight when you threaten him. You say, ‘You had better do that,’ and the dog says, ‘I’ll take your hand off if you try to make me.’

“Flight is the dog who tries to run away. He’ll pull backward, or tremble and lag behind you when you are trying to get him to heel.

“The dog that freezes will just go rigid and throw calming signals like crazy. He’ll go still, lower his body, and will close down in an effort to avoid doing something that will stimulate more of your aggression.

“Then you get the dog who fools around – the one who gets extremely excitable, the class clown. He throws extreme behaviors – pawing and submissively throwing himself down and then jumping up all over you, grabbing the lead, getting tangled . . . this is anxious, insecure behavior. Or the dog who is jumping and wagging his tail, putting his ears back, and pulling his lips back in a big grin is saying, ‘Hey everyone, laugh! And then let’s go do something else now!’

“You may get any (or some combination) of those four responses from using threats on a dog who doesn’t really understand what that is all about. If he’s frightened, and he doesn’t know what he can do to avoid punishment, he’s likely to try some or all of the above.”

Negative results of positive training?

Bondarenko says that the chances of positive-reinforcement training harming the dog’s confidence or psyche are quite slim, though she has seen positive methods, inexpertly applied, cause a dog some frustration and even aggression. The difference is, she says, this resulted in a dog who may be frustrated enough to bark angrily, but who had no reason or trigger to make him attack his handler, whereas a dog who is frustrated and then punished or hurt may well bite to defend himself.

“Positive training gives the dog the opportunity to walk away, to lie down, to stand and do nothing. . . there is lots of room for the dog to avoid being pushed into a very bad, unwanted response,” she says.

Bondarenko sees potential for trouble with positive training in a few, specific instances. For example, when a person has a very confident, independent dog that wants his own way, and is not particularly interested in complying or cooperating, she says, “You have to be able to engage the dog’s interest, you have to get them to want to do it and eager to learn – and not everyone is capable of getting that from their dog.”

And then there are the people who are looking for shortcuts – who just want the dog to be trained as quickly as possible, with little effort. “Behavior shaping is such a wonderful and useful tool, but it’s also complex, demanding, and not everyone can use it very well. Some people use a little bit and then go, ‘Aw, this doesn’t work.’ Or they say, ‘I think it was faster when I just jerked the dog.’ ”

———-

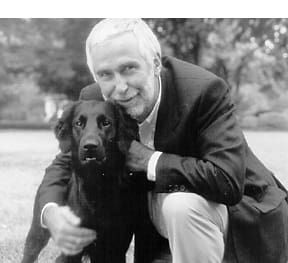

Ian Dunbar: Promoting “Dog-Friendly Dog Training”

Punishment,” says Dr. Ian Dunbar, “is an advertisement that a dog isn’t trained yet.” Dunbar is a veterinarian, has a Ph.D. in animal behavior, and is often credited with pioneering the puppy education movement when he founded Sirius Puppy Training, in Berkeley, California, in 1980. He also has written and produced numerous books and videos on dog training, founded a publishing company (James & Kenneth Publishing) that specializes in books about positive dog training, and founded the Association of Pet Dog Trainers in 1993.

Whether Dunbar has stirred up the wave of positive dog training so popular today or he simply managed to surf its crest for more than 20 years is, perhaps, not worth debating. Throughout that time, he has been a tireless advocate of what he calls “dog-friendly dog training,” focused on helping owners get along with their dogs happily and safely.

To achieve these goals, Dunbar advocates taking the simplest effective approach to dog training possible. Any method of dog training had better be “all the E’s,” he says: “It has to be effective; there is no point in doing it if it doesn’t work. It has to be efficient, because people won’t do it if it takes a long time. It has to be easy, for the same reason. And if it is enjoyable, and people have fun doing it, and their dogs do, too, then they will do more of it, and be more successful.”

For example, Dunbar uses lots of lure-reward training – using a food treat or toy that the dog will follow to get him to perform certain behaviors, such as holding the lure slightly over the dog’s head to get him to sit. He also teaches handlers how to employ the difficult-sounding but fiendishly simple “operant conditioning” – rewarding the dog when he performs the desired behavior or a successively closer approximation, “reinforcing” the desired behavior.

In contrast, undesirable behavior goes unreinforced; the handler strives to make certain that the dog derives no reward from his “bad” behavior, and soon the dog loses interest in repeating it.

While Dunbar does address exotic misbehavior and serious transgressions such as aggression in his books, videos, and lectures, he says the bulk of his work has to do with helping people deal with normal dogs exhibiting normal dog behavior: eliminating in the house, digging in the garden, chewing the family’s possessions, chasing the cat, barking at strangers, and so on.

“What most people want is a dog who is fun and easy to live with,” he explains. “Once upon a time, dog training was all about this military stuff, and practiced mostly by people who wanted to show their dogs in obedience. You used to pick up training books and they would talk mostly about leash corrections.

“But in recent years we began talking about pet dog training, and we invoked the notion of relationship; we’re not just training dogs to do things, we’re training dogs to live with us and be our pals. After all, this is a dog I sit on the couch with and give tummy rubs to. This is the friend I walk with and chat with. I want the dog to like me. I want my dog to enjoy training, and if he does, I will too.

“Within the last 10 years, there has been an explosion of dog-friendly dog training,” Dunbar continues. “Now, the average family living with a dog has so many options, so many new, warm, friendly tools in the toolbox. Now we talk about training dogs to have bite inhibition; to like people, other dogs, and other animals; and we can talk about the notion of dealing with behavior problems.”

Love me, love my training

Dunbar says that in his opinion, the biggest current topic in dog training is teaching trainers and owners alike to avoid punishing their dogs. “My definition of training is to eliminate the need for any punishment,” he says. “If I use a force-based method, my goal is to eliminate that method as soon as possible.”

Dunbar believes there is definite “fallout” from using force- or pain-based training methods. “Even the mildest correction – just saying ‘No!’ – can result in baggage,” he says. “The point of training is to get the dog to like you and to be enjoyable to live with. Trust me, he won’t be fun to live with if he doesn’t like you and doesn’t trust you. In contrast, the fallout of training with treats is that the dog likes the handler.”

Putting yourself in your dog’s shoes is appropriate here; you wouldn’t want to spend hours and hours taking music or dancing lessons from someone with whom you felt uneasy. Dunbar gives an example from his home: “My son has favorite subjects in school because he likes the person who is teaching them. He’s even taking a Chinese history course because the instructor is so wonderful. You want the dog to want to sign up for any course you are teaching – and he won’t do it if he gets yelled at or struck in class.”

Be a behaviorist

When trying to convince people that force-free training actually works far more effectively than positive methods such as lure-reward and operant conditioning, Dunbar says it’s helpful to get them to look at the two different approaches objectively.

“To say I don’t like force-based training, or that dogs don’t like it, is a purely subjective opinion,” he explains. “But you can ask them to use the method that behavioral scientists use to determine effectiveness – to observe and quantify the dog’s behavior.”

Dunbar uses an example of a dog that jumps up. You could, he suggests, deal with the behavior by turning your back and completely ignoring his jumping, while keeping track of how many times he tried to jump. “If you have someone actually keep a log, it not only keeps the person ‘on task,’ but also shows them that, in fact, the method is working. There is no disputing a trend seen in the log.”

Close observation of the dog’s behavior is critical to dog training, says Dunbar. When he is working with a dog, he wants it to feel comfortable and confident, and to enjoy working with him.

“I know I’ve messed up if I see the dog suddenly lower his head and back up, or refuse to join me in the training game,” explains Dunbar. “That’s why I start off by offering the dog a food treat, and observing what he does. Did the dog come? How quickly? His response gives me a good look inside his head. If he takes it, I can be reasonably assured he is comfortable with me, and he can probably be persuaded to enjoy training. If he doesn’t take the food, I give it to the owner and have her offer it to the dog. If he takes it from the owner right away, I know that the dog is uncomfortable with me – and therefore vulnerable to being scared by me.”

As much as he believes that dog training can almost always be accomplished without pain, fear, or force, Dunbar says he doesn’t “attack” force-based trainers or owners who use force. “I don’t look down on anyone for their force-based training methods,” he says. “But I put this question to them: ‘Would you like to do that (use force) less? Because I think I can give you one tip, so you can get the desired result much more effectively and easily.’ If I can show them that I can get the dog to do the same thing quicker, easier, and more enjoyably, they are likely to give the positive stuff a try.”

The trainer does admit to sometimes using covert methods to demonstrate the benefits of non-force methods to a handler who has become angry or frustrated with a dog.

“If someone is in my class and she is ‘losing it’ with her dog, I might put my coffee cup in her hands and say brightly, ‘Could you hold my coffee for a second? Thanks!’ Then I take a handful of treats and get the dog to do what he’s supposed to be doing, and praise both of them lavishly, ‘Goooood dog, goooood job, you two!!’ That conditions both of them to enjoy training!”

-by Nancy Kerns