Canine melanoma is the umbrella term for a group of melanocytic tumor subtypes that are so complex and diverse (yet distinct from each other) that they can sometimes seem as if they are different diseases entirely. What all types of melanomas do have in common is that they form when normal melanocytes (cells that are responsible for producing melanin) divide and grow out of control.

Melanomas are classified as either benign or malignant tumors. Fortunately, the majority of melanomas that occur in dogs are benign; this form of melanoma is typically referred to as a melanocytoma. These tumors are not cancerous and usually do not become cancerous, nor do they interfere with the function of normal cells. They will often cease growing once they reach a certain size and they do not invade other tissues. Furthermore, they do not metastasize, and they tend to not grow back when surgically removed.

In contrast, malignant melanomas, accounting for 5 to 7% of all canine melanomas, are highly aggressive and can metastasize to vital organs very quickly. About 100,000 cases of malignant melanoma in dogs are diagnosed in the U.S. each year.

This cancerous tumor tends to form in areas of the body that are pigmented, and while the tumors are usually brown or black, they can appear pink, tan, or even white, depending on the level of melanin being produced. These are most commonly seen in middle-aged to older dogs (average age of 9 years) with no gender predilection.

The location in the body will determine the specific biological behavior of this cancer. Dogs are often asymptomatic until the cancer has spread.

Causes of Melanoma in Dogs

The etiology of canine melanoma is not known, but researchers believe that it may due to a combination of environmental factors and genetics. It is also suspected that chemical agents, stress, trauma, or excessive licking of a particular spot could be factors; if cells are triggered to randomly multiply, it can increase the chance of mutation during cell division and result in the formation of malignant cells.

While ultraviolet light exposure is a major cause of melanoma in humans, it is not usually associated with the canine form due to their protective coat of fur.

Breed Disposition

Malignant melanoma in dogs is thought to reflect a strong genetic component with the following breeds being over-represented: Airedales, Bloodhounds, Boston Terriers, Chihuahuas, Chow Chow, Cocker Spaniels, Dachshunds, Doberman Pinschers, English Springer Spaniels, Golden Retrievers, Gordon Setters, Irish Setters, Pekingese, Poodles, Rottweilers, Miniature and Giant Schnauzers, Springer Spaniels, Scottish Terriers, and Tibetan Spaniels.

The disease is also more likely to appear in the toes or toenail bed of black dogs; small breeds with heavily pigmented mucous membranes in the mouth are reported to be at an increased risk of oral melanoma.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of canine malignant melanoma is typically obtained through cytology from a fine-needle aspirate of the tumor and/or biopsy and histopathology, but they are also known for being challenging to diagnose.

When melanomas are pigmented, the pathologist can usually see the melanin granules and characteristic cell morphology in the sample. Difficulties arise when melanocytic tumors lack pigmentation and the cell morphology varies tremendously.

The histopathological results of the biopsy may resemble carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, or an osteogenic tumor. At this point, additional testing with special stains for immunohistochemical (IHC) markers (Melan-A, PNL-2, tyrosine reactive protein TRP-1 and TRP-2) is required; this screening is highly sensitive and specific for detecting melanocytes. It is vital to have an accurate diagnosis as that will determine the treatment protocol used and the prognosis.

Further diagnostic tests to assess the dog’s overall health and determine the stage of the disease may include a complete blood count; serum biochemical profile; urinalysis; chest radiographs and abdominal ultrasound to look for evidence of metastasis; and lymph node aspirate to check if cells have spread to the lymphatic system.

In dogs with the oral form of melanoma, especially if the lymph nodes are noted to be enlarged, further testing is warranted to check for metastasis in the abdominal lymph nodes, liver, adrenal glands, and other sites.

For oral tumors, radiographs and/or a computed tomography (CT) scan may be recommended.

Because digital (toe) melanoma often involves bone destruction, radiographs should be taken of the affected foot.

Specific diagnostic techniques for ocular melanoma involve slit-lamp examination, tonometry (intraocular pressure), gonioscopy (exam of the front part of the eye), and fundoscopy (exam of the back of the eye).

Stages of Melanoma in Dogs

The diagnostic tests discussed above will provide the foundation for assigning a stage and grade to the patient’s malignant melanoma.

- Oral malignancies. For these tumors, staging is fairly straightforward and extremely prognostic. While the World Health Organization’s staging system is considered limited in its application (tumor size is not standardized to the size of the patient and histologic appearance and other histologic-based indices are not considered), it is often still used:

- Stage I: Size of primary tumor is less than or equal to 2 centimeters (cm) in diameter with no involvement of lymph nodes.

- Stage II: Size of primary tumor 2 to 4 cm in diameter with no involvement of lymph nodes.

- Stage III: Size of primary tumor greater than or equal to 4 cm in diameter and/or metastasis to lymph nodes.

- Stage IV: Tumor of any size with distant metastasis present.

Alternative staging systems incorporating histologic criteria have been explored, and while a comprehensive approach has unfortunately yet to be developed, these investigations have continued to find that size and location are extremely relevant.

- Non-oral melanoma. The staging system for non-oral forms of canine melanoma is not well defined and further development with clinical variables and outcome is needed.

Histopathologic Grading

There are three histologic features that can be discerned from a biopsy that have been shown to have predictive value. The first, nuclear atypia, is the abnormal appearance of the nucleus of a cell and is considered an indicator of malignancy.

There are several approaches that can be taken to estimate the extent of nuclear atypia, but the assessment is subject to inter-observer variation. It is typically reported as mild, moderate, or severe. Levels greater than or equal to 30% for oral melanomas and greater than or equal to 20% for cutaneous and digit are considered to have poor prognoses.

The second, Ki-67 index, is a quantitative reporting of the cells that are positive for containing the protein Ki-67. This protein increases when cells prepare to divide, and it can be measured with a special staining process. A higher number of positive cells indicates that they are dividing and forming new cells quickly. A Ki-67 proliferative index of greater than or equal to 15% is considered a negative prognostic factor for cutaneous and digital melanomas, as is an index of greater than or equal to 19.5% for oral melanomas.

The mitotic index (MI) is the third and most common feature that can be discerned from a biopsy and is used to estimate the course of the disease. The MI measures the percentage of cells undergoing mitosis (cell division); a higher number of cells that are dividing indicates more aggressive disease. An MI of 3 or higher (out of 10) predicts decreased survival, while an MI of less than 3 predicts a more favorable outlook.

In cutaneous and ocular melanoma cases, the MI is the most reliable element for distinguishing malignant from benign tumors.

[post-sticky note-id=’396308′]Types of Canine Melanoma

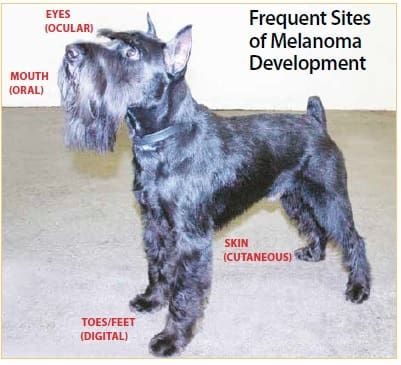

In dogs, there are four primary types of melanoma that can occur: oral (anywhere around the mouth or oral cavity); digital/subungal (around the nail bed and in, on, and between toes); cutaneous (skin); and ocular (in and around the eye). Each type has its own clinical presentation and biological behavior.

Oral Melanoma

Melanomas in and around the mouth are considered the most common oral malignancies that occur in dogs. It is estimated that this cancer accounts for anywhere from 14 to 45% of all oral tumors and 80 to 85% of all malignant melanomas.

This form of melanoma typically occurs in dogs ages 10 years and older and in smaller dogs; dogs with heavily pigmented mucous membranes are at higher risk. Tumors can occur anywhere in the oral cavity and surrounding areas, with the majority found in the gingiva/gums. The next most common site is the lips, and then the hard and soft palate. Fewer than 5% develop on the tongue.

Growths tend to be solitary, appearing as a distinct lump or as a flat plaque-like lesion that may or may not be ulcerated. Tumor colors may vary from black to gray to pink or with varied coloring; up to 33% have no pigment at all. Symptoms can include facial swelling; bad breath/mouth odor; abnormal breathing sounds; difficulty chewing, eating, or swallowing; loose teeth; bleeding from the mouth; excessive salivation; and weight loss.

Malignant oral melanomas are quite locally invasive, often infiltrating nearby tissue and bone. At the time of diagnosis, 57% of cases have radiographic evidence of bone involvement. The likelihood for metastasis is high (80 to 85%) with the most common site being the regional lymph nodes, followed by the lungs and other distant organs.

Digital (Toe) / Subungal (Nailbed) Melanoma

This is the second most common type of malignant melanoma diagnosed in dogs, accounting for 15 to 20% of all melanoma cases and 11% of all tumors involving the digits.

Local invasion is a common feature of this form, with many dogs having evidence of bone damage. Anatomically, the forelimbs are slightly more likely (57.1%) than the hindlimbs (42.9%) to develop a melanocytic tumor.

Dogs with black coats tend to have a higher incidence of the disease. It tends to present as a solitary tumor between the toes, on the foot pad, or on the nailbed, causing swelling of the area and sometimes loss of the toenail.

This type of tumor often develops a secondary infection that can initially misdirect the diagnosis. Lameness is often the first noticeable symptom; swelling with bleeding or discharge from the affected area may also occur, and dogs may lick or chew the area.

Like the oral form of the disease, the digital is extremely aggressive with a dismal metastatic rate of 80%.

Cutaneous Melanoma

This is common in dogs and accounts for about 5 to 7% of all canine skin tumors. These tumors can form anywhere on the skin, and while most are malignant in humans, the majority are benign in dogs.

Benign skin melanomas are usually solitary, small, well-defined, deeply pigmented, firm, and move freely over underlying structures. The malignant form varies considerably in appearance, regardless of the location, and is usually asymmetrical. The color is variable, ranging from gray or brown to black, red, or even dark blue; they may have areas of pigmentation intermingled with areas of no pigment.

Malignant cutaneous melanomas are found most frequently on the head, ventral abdomen, and scrotum. The tumors tend to be fast-growing, and are often ulcerated and have developed a secondary infection. They are typically detected at a late stage with metastasis often detectable in regional lymph nodes. Cutaneous melanomas occurring on a mucocutaneous junction (a region of the body where the mucous membranes transitions to skin) have a higher potential to be aggressive and should be considered for treatment as a malignant form.

Ocular Melanoma

Melanoma can occur in and around a dog’s eyes. It can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva (the mucous membrane that covers the front of the eye and lines the inside of the eyelids), orbit (eye socket/eyeball), limbus (border of the cornea and the sclera), and uvea (the middle layer of the eye). Each location may exhibit different biological behaviors.

The good news is that these are frequently benign and rarely metastasize. That said, they can cause discomfort and problems as they grow, including vision impairment and blindness.

Malignancy tends to occur in the melanomas that form on the conjunctiva and in some of those that form on the eyelid and uveal. Additionally, malignant melanoma existing elsewhere in the body has the potential to metastasize to the eye. In general, ocular melanomas are less aggressive than the oral form; within the ocular melanoma group, the uveal form is characterized as being the most aggressive.

Symptoms of ocular melanoma can include a dark-colored mass in the eye or eyelid, darkening of the iris, irritation and redness of the eye, tearing, cloudy eyes, swelling in or around the eye, and twitching of the muscles around the eye.

Treatment

The first goal of melanoma treatment is to establish local and regional control, which is closely followed by the pursuit of systemic control.

Surgery

This is the primary and most common treatment option for all types of melanoma, including benign tumors. Complete surgical excision of the tumor, surrounding tissue, and any affected bone is required in an effort to obtain clean margins and effective local control. Dogs who have their tumors completely removed with surgery have the lowest chance of experiencing tumor regrowth during their lifetime. Not only can the surgical option occur promptly, it has increased curative intent and tends to be less expensive when compared to other modalities. The extent of the surgery will depend on the anatomic site and size of the melanoma.

Cutaneous melanomas usually require removal by lumpectomy/surgery, while other locations require a more aggressive excision.

Removal of a digital tumor often includes the amputation of the affected toe (with removal of all three phalanges to ensure adequate margins). Surgery to remove melanomas on the larger weight-bearing paw pads can be challenging, as there is the potential for loss of leg function; sometimes amputation of the limb may be the best course of action.

With ocular melanoma, the recommended treatment is enucleation (surgical removal of the eye) when tumors are confined inside the eye.

Oral melanomas may require partial removal of the maxilla or mandible (jaw) bones. While this sounds drastic, dogs tend to do very well after this type of surgery and experience little to no impact on function or quality of life. Cosmetic outcomes tend to be acceptable; if needed, reconstructive surgery can be performed to rebuild these areas.

Other melanoma sites within the oral cavity, such as sublingual or hard palate tumors, are prohibitive for complete surgical removal. Debulking surgeries can, however, reduce the amount of tumor present, but with incomplete surgical removal, oral melanomas tend to regrow quickly (often within days or weeks); subsequently, additional therapy protocols should be considered.

Recently, veterinary specialists have started advocating for removal of the regional lymph nodes and application of radiation therapy to the tumor site if tumor removal is incomplete or the disease has been found to have infiltrated the nodes. It is theorized that this change in protocol might account for the improved survival times occurring in nonvaccinated cases (see “Oncept: A Melanoma Vaccine,” on page 20).

Radiation Therapy

Melanomas were previously considered resistant to radiation therapy (RT), but many more recent studies are finding that there is a significant role for RT in achieving satisfactory local primary tumor control. In particular, RT is an effective treatment for malignant melanomas that cannot be surgically removed due to size or location, or as an adjunct treatment for tumors that either were not, or could not, be completely removed, and/or for cases where the disease has metastasized to local lymph nodes without distant metastasis.

Melanomas tend to respond best to hypofractionated/coarse fraction (radiation given less frequently but in larger doses) RT, typically administered once a week for four weeks and requiring anesthesia. In addition to the tumor site, RT will usually also be administered to the local lymph nodes if metastatic disease has been confirmed.

Side effects from RT tend be uncommon but may include sloughing of nails and foot pad surfaces and mild irritation of the mucous membranes of the mouth. If they do occur, they usually heal within one to two weeks and have minimal impact.

Tumors treated with RT can shrink significantly and may even become undetectable; accordingly, they can remain stable for a period of time. Compared to melanomas treated with surgical removal, however, those treated with RT alone have an increased incidence of recurrence. About 25 to 31% of dogs with oral malignant melanoma that is treated with RT respond partially and 51 to 69% respond completely.

Chemotherapy

Used alone, chemotherapy has not shown to be of much benefit for local control. Because options for treating canine malignant melanoma are fairly limited, chemotherapy has traditionally been used in an attempt to achieve systemic control in combination with surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The drugs typically used in the standard chemotherapy protocols include carboplatin, cisplatin, dacarbazine, melphalan, and doxorubicin.

Unfortunately, there are an increasing number of studies that are demonstrating that chemotherapy as an adjunct treatment does not have a significant impact on either time to progression or overall survival, even when compared to local treatment alone. There is extensive literature on the human counterpart of this approach that suggests melanoma is extremely resistant to chemotherapy. However, chemotherapy has been the most effective treatment available for delaying metastasis until the recent release of the melanoma vaccine (see “A Melanoma Vaccine,” below). At this time, it is still considered a viable but limited treatment option for dogs who don’t respond to the vaccine.

Targeted Chemotherapy

Although not a chemotherapy drug in the traditional sense, Palladia (toceranib) is a novel FDA-approved anticancer drug developed specifically for dogs. While it is labeled for use in dogs diagnosed with mast cell tumors, it has been evaluated for use against other forms of cancer.

Whereas traditional chemotherapy destroys all rapidly dividing cells, Palladia, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is a targeted therapy that inhibits specific receptors on the surface of cancer cells and nearby blood vessels (cutting off blood supply) that may result in delaying tumor growth and the progression of the disease. Palladia may be considered in cases that have become unresponsive to vaccine immunotherapy or standard chemotherapy protocols.

Anecdotal reports present varying responses to the drug, ranging from dogs having stable to partial responses for several months to others having no notable response.

[post-sticky note-id=’396310′]Prognostic Factors

Malignant melanoma is one of the few cancers in dogs for which anatomic location is an extremely important prognostic indicator. Dogs diagnosed with Stage I melanomas have significantly longer survival times than dogs diagnosed with Stage II-IV disease, regardless of treatment chosen.

Negative prognostic factors that affect all types of malignant melanomas include metastasis and size of the tumor.

Oral Melanoma

- Size of primary tumor is prognostic for metastasis and survival time (the smaller the tumor, the better).

- A mitotic index less than or equal to 3 is associated with a better prognosis.

- In general, the closer the tumor is to the front of the mouth, the better the prognosis.

- The median survival time (MST) for untreated dogs is 65 days.

- Survival times following surgery have been estimated at 17 to 18 months for Stage 1; 5 to 6 months for Stage II; 3 months for Stage III, and 1 month for Stage IV.

- Survival time following removal of mandible is 9 to 11 months. In about 22% of the cases, the cancer will recur.

- Survival time following removal of maxilla is about 4.5 to 10 months; about 48% of the cases will recur.

- Response to radiation therapy is about 80%, with survival times of 211 to 363 days.

Digital Melanoma

- The median survival time for dogs without lymph node involvement or metastasis and treated with surgical amputation of the digit is 12 months, with 42 to 57% surviving one year and 11 to 13% surviving two years.

- Digital melanomas not located on the nail bed and having a low mitotic index are often cured with surgery alone.

Cutaneous Melanoma

- Most cutaneous melanomas are benign, in which case the prognosis is excellent.

- About 65% of dogs with cutaneous malignancy succumb within two years due to local recurrence or metastasis.

- Dogs with malignant tumors that are less than 4 cm have a significantly better median survival time (12 months) than tumors greater than or equal to 4 cm (4 months). About 46% of dogs with the malignant tumors that are smaller than 4 cm will survive for at least two years.

- Dogs with well-differentiated malignant tumors and a mitotic index less than or equal to 2 have an MST of 104 weeks.

- Dogs with poorly differentiated malignant tumors and a mitotic index greater than or equal to 3 have an MST of 30 weeks.

Ocular Melanoma

- The majority of ocular melanomas are benign, with an excellent prognosis.

- Uveal is the most common malignant form, characterized by aggressive behavior.

- Only 4 to 8% of malignant uveal melanomas metastasize to lungs and liver.

- Malignant tumors removed by enucleation have a low incidence of reoccurrence.

Stay Vigilant for the Signs of Canine Melanoma

While there are other forms of skin cancer that develop in dogs, melanoma is the most common. If you find any raised lumps or bumps with or without coloration on your dog, consult your veterinarian as soon as possible.

I just did that very thing. My three-year-old mixed breed dog Tico has allergies, requiring frequent baths. I take that time to check him thoroughly – and this time I found a growth on the pad of his paw. We have an appointment next week with a veterinary specialist in internal medicine and oncology. I may be paranoid but after writing this, the fifth article in a series for WDJ on the most common canine cancers, I have earned a little overreaction.

The good news is that canine malignant melanoma is proving to be uniquely responsive to immune-based therapies, and there is evidence that the immune system could modulate the progression and metastasis of the disease. See “On the Horizon: Melanoma Treatments in Development,” on page 22 for more information.

Unfathomable that you didn’t show any pictures

agree – especially the skin cancer. Would love to know what the growths look like. Seeing something on their pads, between their toes, in the mouth or eyes would be a no-brainer to get the dog to a vet but a growth on the skin?

Does it look like a wart, is it flat or raised, could it be mistaken for a tick? Pics would be nice. Everyone can’t afford or get their dog to a vet to see if a bump on the skin or a rash that could be from skin-irritating foliage, is something to be worried about.

1000000% agree.. that’s ridiculous they didn’t “think” to provide several examples of each.

#minimaleffort

I took my 6 yr old Shepherd mix, Jack, for a root canal. The Dr. detected a small pink lump in the back of Jack’s mouth between upper teeth. She didn’t think it looked suspicious, but aspirated and sent it away. We were shocked to find canine melanoma. Dr. removed roof of Jack’s mouth, right to his nose, part of his jaw bone, and some teeth. Thus began such a horrific time. We almost lost him, had to switch hospitals. Once stabilized, Dr’s said that the roof of Jack’s mouth had to be re-established with microscopic surgery. In Canada, we had few options. Nearest to us (in Ottawa) was Auburn Hill’s, Michigan. So me, Jack, Jack’s original dentist and her aunt (Retired RN) made the journey. 11-hour procedure, grafting abdomen muscle into Jack’s mouth. He survived it all, sported an “Elvis sneer.” He contracted anal carcinoma twice. I drove him to Cornell University for radiation and he never skipped a beat, or a meal. He triumphed over cancer and was felled by a botched dental procedure. Bleach was used to clean his teeth and some travelled down his esophagus and burned it severely. Jack lived to be 11 years old. He is my hero.

we are fighting oral malignant melanoma. He is receiving the Oncept altho he still got a second recurrence while on it 🙁 Also giving CBD oil/medicinal mushrooms/chinese herbal/golden paste/home cooked diet – so far so good but I know the prognosis is not good 🙁

All the very best! Mine stayed another 2 years following a similar protocol after being diagnosed with oral malignant melanoma – I hope your boy does just as well, if not better. <3

Diagnosed on 1/31/15 and starting Oncology (Radiation/Vaccine) treatment on 2/4/15 then adding nutritionists and Acupuncture. I even quit my job to be hands on 24/7. No expense was spared.

Six months later on August 23, 2015 he licked my face and in his eyes I could see it was time. That day, I lost my Lhasa (and a part of me) to Oral Malignant Melanoma. Such a beautiful dog, it broke me to watch him go through so much. It is my hope that 1 day there will be a cure.

Sorry for your loss, Sharon. In case I ever have to make such a hard treatment choice could I ask what side effects the treatment had? Like what was the quality of his life during treatment?

Diagnosed on 1/31/15 and starting Oncology (Radiation/Vaccine) treatment on 2/4/15 then adding nutritionists and Acupuncture. I even quit my job to be hands on 24/7. No expense was spared.

Six months later on August 23, 2015 he licked my face and in his eyes I could see it was time. That day, I lost my Lhasa (and a part of me) to Oral Malignant Melanoma. Such a beautiful dog, it broke me to watch him go through so much. It is my hope that 1 day there will be a cure.

Thank you for this article and the awareness you bring to others.

I really want to see some pictures about this disease to get to know more about the growth of it.

My dog Rocky (beagle/hound mix) was diagnosed Feb 10, 2020 with malignant melanoma. The growth started in his shoulder area & in 4 months grew to the size of a dime, it was black with irregular borders and looked like a raised black mole. It’s a very aggressive type but we are treating him with the Oncept vaccine. Rocky is such a happy dog, I’m praying he will survive at least another year. He’s 12 or 13.

Great article. My dog is 15 yrs 10 months today. He was diagnosed with Malignant Melanoma on his outer gum on the left side in May. Surgery to remove done in June. It came back 21 days later. I wanted to do vaccines but couldn’t afford $3000 every two weeks. I also didn’t do radiation because I couldn’t leave my boy for so long. He has been a trooper. I’m using home cooked meals, supplement including lifegold & using homeopathics. He’s been eating, going potty and even playful on occasion. But he has made a change the last two days… it’s very hard. He’s a flat coat retriever mix, 80 lbs. Sweetest dog I’ve ever known. He beat Leiomysarcoma 4 years ago. The drainage from his nose is awful & the smell almost makes me sick. I’m wondering if some dogs ever die naturally from this horrible type of cancer?

so sorry to hear what you are going thru, I am amazed he has lived a long life for an 80lb dog!

Thank you Brit. My sweet boy died on Christmas Eve. I’m heartbroken. He was such a love sponge. This is a horrible cancer.

Great article ,but could you post info on cebacious cysts?

My 13 year old cairn terrier was diagnosed in December with cutaneous malignant melanoma and had surgery to remove. We started the melanoma vaccine in January and she just had her fourth shot. The tumor came back at the same site exactly three months after surgical removal, and right around her third shot (one every two weeks for four total). Because of how close it is to her tear duct another surgery would have to be much more aggressive and she’d likely lose her eye and possibly bone. With 10 out of 10 on mitotic index, the oncologist feels it will come back again anyway no matter how aggressive the surgery. The vet said if it was her dog, she wouldn’t do the surgery because of how aggressive this cancer is. Instead, we started her on the Palladia and in a couple weeks (She’ll have been on it a month) so we can see if it is helping. Her lungs are clear and lymph nodes Ok but they’ll recheck again in a couple weeks to be sure. I opted not to do radiation because of risk if Injury to her eye and because it’s under anesthesia. At 13 I didn’t want to keep putting her under another six times for radiation. As soon as she’s fasted she knows she’s going to the vet and stresses out – especially after the last time she was in horrible pain for days after surgery. Of course, I’m now second guessing myself and wishing I had done the radiation instead of the vaccine. Apparently because of how aggressive this cancer is no matter what I do now or would’ve done before, the prognosis is bleak. I’m devastated, obviously. I’m also giving her CBD oil and low carb food, which she hates. In January the oncologist thought a year but now that it came back again I’m not sure. It grew so rapidly the first time and this time again. I caught this really early because of where it was. Her regular vet didn’t think it was anything but I wanted a biopsy, which came back atypical cells. Between the day I found it (12/9) and two weeks later when removed, it was tripled in size. Went from a little flesh colored bump to black wart like protruding growth. Sorry to ramble on. Unfortunately, there aren’t any better treatments for this disease now than there were however many years ago this article was written. All I can do now is try to keep her as comfortable as possible for as long as possible and pray I can let her go when I have to.